Klaus Störtebeker: The Bizarre Tale of a North German Pirate

Looking to the past, the annals of history have its fair share of extraordinary and unusual deaths, some more famous than others. It’s well known that Attila the Hun, the marauding Mongolian warlord, was killed by a nosebleed, and that Adolf Frederick of Sweden ate himself to death in 1771 after consuming caviar, lobster, kippers, and 14 servings of his favorite dessert. Lesser noted, but equally as outlandish was the death of Klaus Störtebeker, a 14th century German pirate, whose remarkable decapitation and spike-pierced skull still hold revered places in the pantheon of German national mythology.

Klaus Störtebeker was born in 1360 in the North German town of Wismar. Not much is known about the early life of this elusive brigand, apart from an incident in 1380 when two men, one with the name Nicolao Störtebeker, were thrown out of Wismar after engaging in a violent fistfight. This incident was characteristic of the recalcitrant corsair who was also famed for his drinking exploits. His second name, Störtebeker, can be translated from German to ‘down the beakerful’, and references the pirate’s legendary drinking skills and his ability to finish a 4 liter mug of beer in 1 gulp. Störtebeker was also a renowned marauder, and from 1389 led a band of avaricious pirates known as the “ vitalin brethren” or “ Victual Brothers,” unleashing havoc upon the waves of the Baltic Sea for the next decade.

A reconstruction of the head from skull ascribed to the notorious German pirate Klaus Störtebeker. (Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Klaus Störtebeker and the Battle for Baltic Supremacy

Störtebeker got his first break as leader of the Victual Brothers, a band of cutthroat privateers who roamed the Baltic Sea during the 1390s.

The first mention of the Victual Brothers was in 1389, when the town council of Dorpat responded to a letter sent by Reval, who complained that they had sold ships to “ de vitalienbrude.” Reval’s indignation probably stemmed from the fact that the Victual Brothers may well have already been a notable presence in the Baltic Sea at the time, with a murky reputation both as a distrustful professional force for hire as well as a marauding gang of pirates. In 1390, the Hamburg Chamber of Finance reported that an armada of ships had been sent to fight against the “ Vitalienses.”

- The Intricate World of Pirates, Privateers, Buccaneers, and Corsairs

- Thames Shipwreck identified as Cherabin, English pirate ship that pillaged for the Queen

Störtebeker’s employment with the German royal house of Mecklenburg remains the most documented period of his life. Following the death of Waldemar IV Atterdag, king of Denmark from 1321 to 1375, a struggle for the Danish and Swedish throne ensued between the deceased king’s daughter, Queen Margaret of Norway, and the King of Sweden, Albrecht III, who was also the son of the Duke of Mecklenburg, based in Germany. Using his seaports at Wismar and Rostock, Albrecht III started to hire privateers for the express purpose of harassing and destroying Danish ships in the Baltic Sea in the hope that Queen Margaret would surrender her claims.

In 1392, during one of these recruitment drives, Störtebeker and his men were hired and quickly put to work by the Germans. Their first major mission was in 1394, when they were ordered to supply besieged Stockholm with supplies. For this they were named the “Victual Brothers,” which derived from the Latin word victualia, meaning foodstuffs or provisions.

Contemporary evidence from Franciscan friar, Detmar, writing in 1395, showed that Störtebeker had lain waste to the Baltic Sea. He reported that by their actions, the Victual Brothers had managed to seriously disrupt the oceans, and were even guilty of attacks on allies:

“But unfortunately they threatened the entire sea and all merchants, and robbed both sides, friend and foe, so that the way to Scania was closed for about three years. Because of that, herring became very expensive in these years.”

The blockade of Scania was also mentioned by two further sources from Magdeburg and Limburg, who both reported an increase in the price of salt-herring, an essential part of the diets of everyday people.

When a peace treaty was brokered in 1395 between the two warring factions, with Albrecht forced to relinquish control of Sweden and Denmark to Queen Margaret, nothing much changed. Störtebeker and his brothers had gotten accustomed to the taste of plunder and pillage, and after leaving the service of the Germans continued to engage in piracy, spreading fear to all those who dared sail the Baltic Sea. Margaret would eventually finalize her control of the Danish and Swedish throne in 1397, creating the Kalmar Union, as Störtebeker unleashed pandemonium on the high seas.

At the time, the Baltic Sea trade was dominated by the Hanseatic League, a trade alliance of North German states who were moving incredible amounts of gold and goods out of Hamburg, Lübeck, and Rostock. Störtebeker, sensing opportunity, set up base on the island of Gotland, turning the largest town, Visby, into a pirate stronghold. After several years of successful haranguing, the island was invaded by knights of the Teutonic Order in 1398 and Störtebeker’s ruffians were driven out of the Baltic Sea and forced to find another safe haven on the rugged coastlines of the North Sea. Finding common ground with the Frisians, who inhabited modern-day Holland, the outlaws started to target the shipping lanes to England and the English Channel. However, their luck would eventually run out.

The summary execution of Klaus Störtebeker in Hamburg, Germany in 1401 AD in a tinted woodcut by Nicolaus Sauer. (r_gassenhower / Public domain)

The Downfall and Execution of Klaus Störtebeker

After a further 4 years of success, Störtebeker was finally stopped by the Germans of Hamburg and Lübeck, who sent a flotilla of ships under the captaincy of Simon of Utrecht to attack Frisia in 1401. Störtebeker and his crew were captured by the Hamburg englandfahrer company, with only his loyal co-corsair Gödeke Michels managing to escape their clutches. They eventually caught up to him on the Jade, a delta of the river Weser, where he was killed a year later in a final stand-off. Störtebeker was allegedly betrayed by one if his crewmates, who had purportedly poured molten lead on the chains that controlled the ship’s rudder, leaving his ship unable to move.

Störtebeker and his crewmates were transported to the island of Heligoland and then Hamburg on a frigate called the Bunte Kuh or “Motley Cow,” to await judgement. In desperation, the devious delinquent offered his captors a gold chain that could wrap around the entire circumference of Hamburg in exchange for his release. Störtebeker did indeed possess an enormous amount of gold as a result of his raids. When apprehended, the gold reclaimed from his ship was supposedly used to later construct the tip of St Catherine’s Cathedral in Hamburg. Nevertheless, the Germans remained unconvinced by his offer, and sentenced him alongside 70 of his crewmates to death by beheading.

The execution of Klaus Störtebeker, which happened on October 20th at the island of Grasbrook on the Elbe River outside of Hamburg, was possibly one of the most bizarre in the pages of recorded time. Realizing he was at his end, Störtebeker struck a peculiar deal with the executioner and the city councilors of Hamburg. They agreed that after his decapitation his headless body was to be allowed to walk past the other incarcerated freebooters and for those men to be released. When the headsman lopped his head off, Klaus Störtebeker’s body stumbled past 11 of his men, and was only prevented from walking further when the executioner tripped him up. However, the Germans did not keep their end of the bargain, and the rest of Störtebeker’s pillagers were swiftly guillotined alongside their enigmatic captain, and their heads set on pikes outside the Hamburg city walls as a warning to other would-be bandits.

- Port Royal and the Real Pirates of the Caribbean

- Unexplored Sunken Pirate City in the Caribbean Will Finally Be Revealed

An amusing epilogue concluded the legend of Klaus Störtebeker’s execution. After he had dispatched all the prisoners, the city councilors asked the executioner if his arms were tired as a result. In jest, he responded that his arms were fine and that he even had enough energy to decapitate all the members of the council. The joke fell flat, and the executioner was also sentenced to death, being executed by the youngest member of the city council.

Hundreds of years later, in 1878, a skull with a spike driven through it was unearthed at the very same spot Störtebeker met his end, at Grasbrook. Believing to have belonged to Störtebeker, whose head was allegedly impaled on a spike, it was eventually displayed in the Museum for Hamburg History in 1922. In 2008, in an attempt to conclusively link the skull to Störtebeker, DNA samples were taken from the cranium and possible surviving descendants for comparison. Although the results were inconclusive, the skull is still attributed to Störtebeker and proudly displayed at the Museum for Hamburg History alongside a digital reconstruction of the raider’s face.

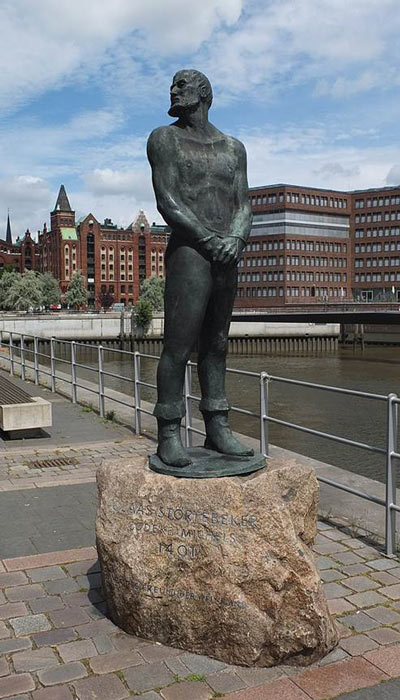

Klaus Störtebeker remains a famous hero in German folklore, and is celebrated for his Robin Hood approach to banditry as this statue in the very city where he was decapitated attests to. Störtebeker memorial in Hamburg. (Palauenc05 / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Legacy of Klaus Störtebeker in Germany

To this day, Klaus Störtebeker remains a famous hero in German folklore, and is celebrated for his Robin-Hood approach to banditry. Many other versions of his legend mention that he also gave his spoils to the poor, and his mercenary outfit was often given the epithet ‘ likedeelers’, which meant they divided plunder equally.

In Germany, Klaus Störtebeker has been revived at various times in its history during the post-World War One socialist period, Nazi era, Communist era, and even more recently at the turn of the century.

In 2008, he was the star of the national celebration of German reunification, featuring in a theatrical production called ‘ Störtebeker, a North German Pirate’. Since 1959, starting in communist east Germany, Störtebeker has been the subject of numerous plays at the annual Störtebeker Festspiele held on the island of Rugen, which in 2007 attracted 378,000 visitors. His renaissance in the late 2000s was a response to Germany’s deepening economic crisis and a growing sense of inequality pervading society, as Germans were rocked by the news that they were the only European country where real wages fell from 2000 to 2008.

This was immortalized in a 2008 feature film entitled ’ 13 Paces Without a Head’, which dramatized his swashbuckling adventures. Ronald Zehrfeld, who played Störtebeker, summarized German feelings towards the pirate: “He butchers people, but also has a very, very big heart.” Despite his criminal tendencies, Störtebeker remains an icon of German popular culture, and is remembered as a statue at the Hafencity memorial as ‘God’s friend, the world’s enemy’. He was so admired that a few over-eager Störtebeker enthusiasts took their reverence for the old pirate a little too far when the skull was stolen in 2010, only to be fortunately retrieved the next year.

Was Klaus Störtebeker real?

In a story as preposterous as Klaus Störtebeker’s, it is impossible to avoid the inevitable intermingling of fact and fiction. Although Störtebeker’s myth was based on a real historical person, George Rohman has argued that the surreal execution of Klaus Störtebeker is an invention. He has argued that the Victual Brothers continued to exist after 1401, being referenced in 1436 and as late as the 1460s in Lübeck.

- Be My Matelotage! The Civil Union of 17th Century Pirates

- 10 Of The Most Famous Pirates, Male And Female, Who Ruled The Seas!

This is because it is possible that the ‘ vitalian bretheren’ was a more general term for privateers in northern Europe and not exclusively linked with Störtebeker and his crew. A letter of consignment from Count Albrecht of Holland, for instance, imploring the ‘ vitalian bretheren’ to help him fight against his enemies, the Frisians, illustrates that it was not only Mecklenburg that had hired the services of the group. In addition, he claims that the historical individual who Störtebeker was based on was still alive until at least 1413 or as far along as 1436 according to tax records.

For Germans, however, the tale of Klaus Störtebeker is less about the fantastical circumstances of his death and more about his stance as a champion of the poor and disruptor of authority. The appeal of Störtebeker’s story continues to show the dedication of ordinary Germans in the fight against inequality, and the unlikely lasting power of an old pirate tale on the national consciousness.

Top image: Klaus Störtebeker was part of the Victual Brothers pirate band that terrorized the Baltic Sea until . . . Source: waewkid / Adobe Stock

By Jake Leigh-Howarth

References

Dewey, D. 2019. Sea Wolves. Scandinavian Review, 74:1.

Stolze, D. 2015. The impaled cranium that allegedly belonged to a 14th century pirate. Stranger Remains. Available at: https://strangeremains.com/2015/05/16/the-impaled-cranium-that-allegedly-belonged-to-a-14th-century-pirate/ .

Stuchberry, M. 2019. Klaus Störtebeker: Infamous German pirate and ‘Robin Hood’ of the high seas. The Local. Available at: https://www.thelocal.de/20190425/klaus-strtebeker-germanys-most-famous-pirate-and-robin-hood-of-the-waves/ .

Historical Piracy: Klaus Störtebeker. Hamburg. Available at: https://www.hamburg.com/sights/maritime/13082800/stoertebeker/ .

Kulish, M. 2008. In German Hearts, a Pirate Spreads the Plunder Again. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/06/world/europe/06pirate.html .

Rohman, G. Did the activity of the ‘Vitalian Brethren’ prevent trade in the Baltic area?. Boydell Press. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/31409022/Did_the_Activity_of_the_Vitalian_Brethren_prevent_Trade_in_the_Baltic_Area_in_Christian_Buchet_Hg_The_Sea_in_History_La_mer_dans_l_histoire_Bd_2_The_Medieval_World_Le_moyen_âge_hg_von_Michel_Balard_Martlesham_Rochester_NY_2017_S_585_594.

Comments

And why wouldn't this rouge be mythical? Scoundrels like Robin Hood are often honored by their heirs. Kinda like Blackbeard and Genghis Khan. Interesting tale though...

It does make one wonder how many of our honored founders were truly not so virtuous...Skull worship is always weird.