Ancient Greek Physician Hippocrates and the Medical Revolution

Classical Greece is considered by many to be the birthplace of modern Western civilization. The ancient Greeks made astounding progress in a huge number of areas - from politics and governing to religious practice and philosophical thought. The impact the Hellenic culture had is still felt throughout the world today.

Archimedes, Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Homer – the list of figures from ancient Greece who have left their mark on the world today is astounding and the innovations and principles they pioneered surround us in our day-to-day lives.

One ancient Greek whose influence is still felt the world over is Hippocrates – a physician who is widely known as the father of modern or clinical medicine. Medicine and healthcare had been practiced for thousands of years. The healing properties of things such as willow bark, cannabis, and poppies were recognized and taken advantage of long before the rise of the Classical World.

So, what made Hippocrates different from the physicians and healers who came before him? And is his influence really still felt throughout the world today?

The Life and Legends of Hippocrates

Hippocrates was born around 460 BC on the Aegean Island of Kos. His family was relatively wealthy – his father, Heracleides, is thought to have been a physician and his mother, Praxitela, was the daughter of a nobleman.

His family’s wealth meant he received a good education. He initially studied for nine years and his education had a wide curriculum covering reading, writing, spelling, poetry, singing, music, and physical education.

After this, he studied at a secondary school for two years and then went on to study medicine. He was tutored by both his father and his grandfather (who was also a physician named Hippocrates). His training is likely to have involved trips to mainland Europe, Libya, and Egypt where he gained a great deal of experience and encountered many different medical problems.

His training was probably conducted at an asklepeion, which was a type of temple in ancient Greece dedicated to the mythological demi-god Asklepius, who was also a physician. These temples were staffed by skilled healers who functioned as rudimentary doctors and surgeons.

Asklepieion on Kos where Hippocrates studied medicine. (Rmrfstar / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Some texts refer to Hippocrates studying with a Thracian physician called Herodicus of Selymbria as well as his father and grandfather, and his education was further rounded out by study with the philosophers Democritus and Gorgias.

He was such a significant figure that many legends grew around him after his death, and a detailed family tree was drawn up which led back to Asklepius on his father’s side and Heracles on his mother’s side. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a text from the 14 th century describes him as the ‘ruler of Kos and Lango’ and recounts a fantastical tale about his daughter. According to the text, she was turned into a hundred-foot-long dragon who could only be brought back by the kiss of a knight.

As preposterous as this is, it is an ideal example of the way Hippocrates was perceived as somehow better than human even hundreds of years after his death.

Hippocrates’ Work as a Healer

Before Hippocrates, sickness was seen as the result of evil spirits or a curse by the gods. Although basic healing methods were known, they were understood to be a way of communicating with the gods or seeking their approval.

Hippocrates was able to see beyond this primitive way of thinking and apply logic and reasoning when looking for ways to heal his patients. Rather than attributing a disease to the wrath of the gods, he believed it must have a natural cause.

He was extremely professional in his conduct, and in his work ‘ On the Physician’ he stated that physicians should always be well-kept, calm, serious, understanding, and honest with their patients. He was rigorous in his own practice of these standards.

A number of ancient Greek surgical tools. On the left is a trephine; on the right, a set of scalpels. Hippocratic medicine made good use of these tools. (Rmrfstar / Public Domain)

He valued the observation of patients, as well as detailed documentation of their symptoms and treatment. He believed it was important to make notes in a clear and understandable way so that they could be passed to other physicians who may treat the same patient, or to future physicians who may have a patient with the same affliction.

Many of the things he made notes on himself are standard today – he took the pulse of his patients, as well as noting whether they had a fever and what pains they described. He was so thorough that he also made notes on the family history of his patients and the environment they were living in.

- Severed Limbs and Wooden Feet: How the Ancients Invented Prosthetics

- The Ebers Papyrus: Medico-Magical Beliefs and Treatments Revealed in Ancient Egyptian Medical Text

- A Dream Cure? The Effective Healing Power of Dream Incubation in Ancient Greece

Dispute of Posidonius and Hippocrates, examining sick twins, on the influence of the stars on the health of man; the parents of the twins in the foreground. (Picryl / Public Domain)

Hippocratic Fingers

The detailed notes Hippocrates and his followers made meant they were the first to describe many of the conditions we know today. He described clubbing of the fingers in great detail – a symptom of several serious diseases such as lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbed fingers are sometimes known as Hippocratic Fingers.

Clubbing of fingers in a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome; first described by Hippocrates, clubbing is also known as ‘Hippocratic fingers’. (Ann McGrath / Public Domain)

His thorough descriptions of pallor and appearance meant he recognized the change in expression and skin tone which signals impeding death. His writings described the appearance of the patient before death as “the nose sharp, the eyes sunken, the temples fallen in, the ears cold and drawn in and their lobes distorted, the skin of the face hard, stretched and dry, and the color of the face pale or dusky”. This phenomenon is known today as facies Hippocratica (the Hippocratic Face).

His descriptions and treatments for thoracic empyema are crude, but they are nonetheless still relevant and would be considered useful today.

Hippocrates Theory of Unbalanced Humors

Although Hippocrates offered detailed and accurate descriptions of a wide number of maladies, his ideas about what caused them were no more accurate than the beliefs held by his predecessors.

In his work ‘ The Sacred Disease’ he explains that if diseases were caused by supernatural entities, medicines would not have any effect on them. He proposed that diseases were actually caused by unbalanced humors – an idea which was then widely accepted in ancient Greece and which persisted in ancient Rome.

The humourism that Hippocrates proposed argued that the human body was made up of four main elements – blood, yellow bile, phlegm, and black bile. Diseases were caused by an imbalance in these humors, and the level of imbalance dictated the disease and its symptoms. An excess of yellow bile, for example, was believed to cause ‘warm’ diseases, while an excess of phlegm would cause ‘cold’ diseases.

If there was not an excess or lack of any particular humor, the problem could be caused by a corruption of the humors. This corruption could be a result of many things such as diet or environment, which is why Hippocrates went to such great lengths to make sure these things were listed when describing a patient.

He believed many treatments could be prescribed based on what had been diagnosed as the problem with the humors, and in many cases he recommended a change in diet or an increase in exercise as a way of improving health.

The Hippocratic Corpus

With such a strong emphasis put on the taking of accurate and comprehensive notes, it is not surprising Hippocrates was also prolific at writing down his findings. Hippocrates left behind a corpus of 70 books about medicine and medicinal practices and these are the oldest known medical texts. Although the books are in the Hippocratic tradition, it is not known how many of them may have been written by his followers and there is much debate about this among scholars and historians today.

Table of contents in a fourteenth-century Hippocratic Corpus manuscript. (Wareh / Public Domain)

The books were aimed at different audiences, with different purposes in mind. Some of his work was aimed at physicians, while other books were written for the layman to understand the basics of medicine.

He taught a great deal about the humors and the treatment of disease in his books, but he also described the methods to treat physical afflictions such as dislocated and broken limbs. While these physical problems were not attributed to problems with the humors, he felt it was important to treat them in the same manner each time, and he made sure his followers had standardized instructions for the treatment of these issues.

There were textbooks, lectures, research notes, and philosophical essays – but the most famous of all the Hippocratic texts is the Hippocratic Oath.

The Hippocratic Oath

Hippocrates and his followers may have pioneered a number of medical practices and been the first to describe many conditions – but perhaps the most significant legacy left behind by Hippocrates is the Hippocratic Oath.

Rather than describing diseases or offering suggestions for their treatment, the Hippocratic Oath is a code of ethics for physicians. It originally called on the physician to swear by several healing gods and to abide by a set of specific ethical standards while practicing medicine.

It is the earliest Western code of ethics in the medical field, and it established the need for confidentiality and doing nothing to knowingly harm a patient. The ethics laid out in the oath are so seminal that the Hippocratic Oath (or in some cases a modernized version of it) is still recited by thousands of medical students every year and it is upheld with utmost seriousness by those who take it.

- How the Ancient World Invoked the Dead to Help the Living

- The Urine Wheel and Uroscopy: What Your Wee Could Tell a Medieval Doctor

- Negotiating with Death: Special Agreements for the Afterlife Around the World

A 12th-century Byzantine manuscript of the Hippocratic Oath in the form of a cross, (Rmrfstar / Public Domain)

The oldest surviving example of the oath dates from 275 AD showing just how long the oath has been relevant and important to physicians and patients alike. The oaths which have begun to replace the Hippocratic Oath do not dismiss it or feel the principles are outdated.

They have simply added more detail which helps provide a clearer code of ethics for physicians now that medical practice has moved on so far and new ethical dilemmas have arisen. The appeal to healing gods has been removed so it becomes secular, but it has also been adapted to refer to the Christian God and this version was the most popular for many decades.

Breaking the Hippocratic Oath today is not against the law, but it is so central to the way that medicine is practiced today that to do so would almost certainly constitute some form of medical malpractice – for example violating the confidentiality of a patient is a violation of HIPAA today, but it is also breaking the Hippocratic Oath. In the past, breaking the oath would have resulted in losing the right to practice medicine or other penalties.

Hippocrates’ Legacy

Very little is known about his death, but Hippocrates is rumored to have lived to well over 100 years old. In reality, evidence suggests he was in his late 80s or early 90s when he died.

He lived a long and very fruitful life and his longevity was probably at least partly thanks to his experience and skill as a physician. He left behind his large corpus of work and a world which saw health and sickness in very different terms to the previous generation.

Hippocrates’ Aphorismi manuscript. (Fæ / Public Domain)

The ideas Hippocrates had about health and disease were revolutionary. They challenged hundreds, or even thousands of years of belief, and yet many people saw how much healthcare was improving by following his practices. His work and ideas advanced Western medicine significantly and offered an entirely new way of treating patients.

Unfortunately, after his death advancement in medical techniques and practices stalled. People believed his methods were so perfect they could not be improved upon and it was not until almost 400 years later that any major changes in standard practice were made. His methods were adopted again in the Middle Ages across the Islamic world and in Europe they became popular after the Renaissance.

Although his belief that humors were the cause of disease was misguided, Hippocrates’ way of thinking changed medical practice forever. Sickness and diseases were no longer blamed on the supernatural and people began to treat problems in a methodical way. Although taking the original Hippocratic Oath has lost some of its popularity in the past decades, in lieu of modernized versions which are more relevant in the 21 st Century, the ideas and guidance Hippocrates left have been at the heart of Western medical practice for thousands of years.

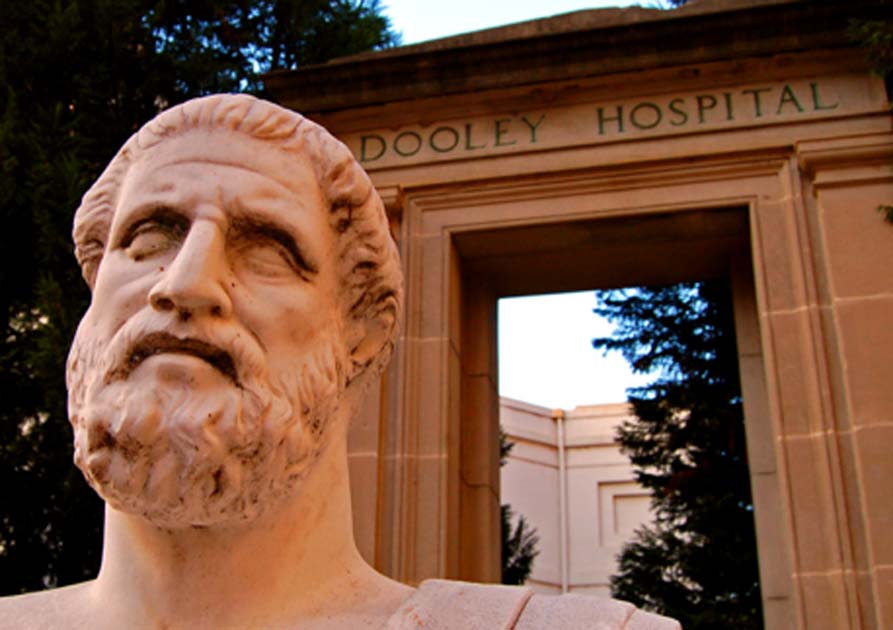

Top image: Hippocrates Statue and Dooley Hospital Door . Source: CC BY 2.0

References

Famous Biologists. Date unknown. Hippocrates. [Online] Available at: http://famousbiologists.org/hippocrates/

Jouanna, J. 1998. Hippocrates. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kanellou, V. 2004. Ancient Greek medicine as the foundations of contemporary medicine. Techniques in Coloproctology.

Longrigg, J. 1998. Greek Medicine From the Heroic to the Hellenistic Age. Taylor & Francis.

Pedersen, T. 2018. Who Was Hippocrates? LiveScience. [Online] Available at: https://www.livescience.com/62515-hippocrates.html

Theoi. Date unknown. Asklepios. [Online] Available at: https://www.theoi.com/Ouranios/Asklepios.html

Comments

The modernise oath is ........... "Follow the money"

Hippo' was wrong in his belief of the causes of disease as doctors today are wrong as to the causes of disease. For example, there is no such thing as bacteria being a pathogen and nobody has ever seen a Virus. Retro viruses have not in 150 years of modern medicine caused a problem..... until now when modern medicine says it causes AIDs......... and so it does.

"He was extremely professional in his conduct,"

He was either professional or not, one cannot be extremely professional.

This folks, is how you can tell that the article was written by an American person. They just can't speak English.

It’s quite clear Hippocrates was more than likely the first “modern” doctor. He was a physician in the truest sense and we owe so much to him. But, just as in ancient times, doctors aren’t gods and their work is not perfect. It’s called a “practice” for a reason.