Emperor Justinian the Great: The Life and Rule of a Visionary Roman

From the numerous emperors in the long and exciting history of Rome and Byzantium, one manages to stand apart – Justinian the Great. His rule marked a turning point, an opening of a new era filled with revolutionary changes on the grand stage of Europe. It brought a renewed spark, a surge of hope for the once great Roman Empire – hope that would never be as strong in the following centuries.

Shrewd and tactful, daring and wise, Justinian managed to rise from nothing, all the way to the loftiest heights of history. Driven by the desire to rebuild the ravaged Roman Empire, his accomplishments rightfully earned him the nickname ‘Great’. Today we’ll recount his story, reminding ourselves of the golden age of the Byzantine Empire and the man who helped create it.

A mosaic of an older Justinian. Source: Jbribeiro1 / CC BY-SA 4.0.

From Rags to Riches – Emperor Justinian’s Rise to Power

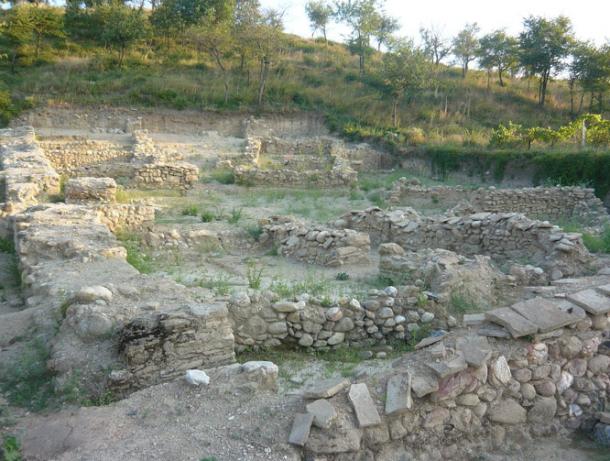

Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus Augustus – or Justinian for short, was born sometime after 450 AD, as a member of a lower caste peasant family in the village of Tauresium, in the Roman province of Dardania. Thanks to his uncle Justin – who would be the future emperor – Justinian wasn’t destined for a common villager’s life. Instead, his uncle took him to Constantinople, where he would be educated in theology, law, and history, rising in influence alongside his uncle, and even serving in the ranks of the Excubitors – the imperial guard, at whose head was his uncle Justin.

The ancient town of Tauresium, the birthplace of Justinian I, located in today's Republic of Macedonia. (Dvacet / Public Domain)

When the Emperor Anastasius died, it was Justin who managed to rise through the ranks of the imperial guard and become the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. He rose from a family of swine herders. Being in his sixties, and lacking a son of his own, Justin was forced to consider his nephews as his future successor.

And the chief among his nephews was none other than Flavius Petrus – the son of his sister. Justin took to educating him and eventually adopted him. In turn, Flavius Petrus added ‘Justinianus’ to his name, showcasing the gratitude to his benefactor.

In the following years, Justinian became an ambitious advisor to the now old Emperor Justin. When the latter became ill and increasingly senile, he decided to make his nephew Justinian the co-emperor. This happened in 527.

But the truth is, that Justinian was the de-facto ruler, even as early as 518, as Justin was increasingly incapable of rule in the last years of his life. Either way, just four months after proclaiming his nephew the co-emperor, Justin died on 1 st of August 527, leaving the throne to Justinian – the new emperor of the Byzantine Empire.

A Turbulent Start: Justinian’s Early Rule

Justinian’s first official years as a ruler were a proper test of his skills, as they were full of new developments that required stern decisions. One of his earliest undertakings, and the one that brought him widespread fame later in history, is the so-called Corpus Juris Civilis – a collection of judicial reforms that were aimed as a complete revision of all Roman laws.

Two manuscript fragments of the Corpus Iuris Civilis, issued by order of Emperor Justinian I. (Fæ / Public Domain)

He also dealt with legislation, aiming it at paganism and its worshippers – they were effectively banned from all practice and forced into exile and even death. Around 532, early in Justinian’s reign, his rule would come into the greatest danger – growing from a triviality into a crucial problem.

Violence was an issue in Constantinople at that time, most of it stemmed from rival factions of chariot racing supporters. The two factions, the Blues and the Greens, grew restless and were often causing minor riots throughout the city. Their complaints were usually directed at the unpopular officials that Justinian placed into important positions.

The riots incited more ruthlessness from the government and more unpopular officials to be put into service – the problem became a vicious circle. And it was this problem that would give birth to the biggest threat of Justinian’s rule – the Nika riots.

In January of 532, this growing unrest would escalate, with the rivaling factions uniting and adopting their battle cry – Nika! (Greek for ‘ Conquer!’) and inciting a rebellion that was based around the imprisonment of two members of their factions. This rebellion escalated quickly and became the most violent riot in the history of Constantinople.

Raging mobs pillaged and burned through the town, aiming to depose Justinian and place a new emperor on the throne. In response, Justinian tasked his two most able generals – Mundus and Belisarius – with quelling the riots, which they were unable to do.

Faced with an almost deadly situation, Justinian managed to bribe the Blues faction at the last moment, and subsequently massacred the gathered Greens and other rebels in the hippodrome. The riots lasted for a week and left half of the town burned down, with over 30,000 people killed.

But managing to quell this uprising, Justinian successfully solidified his rule and used the opportunity to rebuild Constantinople and raised several splendid buildings, the chief of which is the world renowned Hagia Sophia cathedral.

An angel shows Justinian a model of Hagia Sophia in a vision. (GifTagger / Public Domain)

The Reign of a Conqueror: The Restoration of an Empire

The Nika riots were the first major obstacle in Justinian’s rule, but it didn’t manage to sway him from his biggest intention – the restoration of the Roman Empire, or renovatio imperii, as it was called. This re-conquest of the lost Roman provinces would become the crowning jewel of Justinian’s entire reign, and one of the last significant expansions of the Byzantine Empire.

Even before the Nika riots, Justinian had been at war with the Sassanid Empire in the east, just as his uncle Justin was. From 527 the war was the primary focus. Under the command of the skilled general Belisarius, the Byzantines won two battles in 530, only to suffer a defeat in 531.

But that same year the Persian king died, and a deal was struck with his young heir – the so-called ‘Eternal Peace’, which cost Justinian an astonishing 11,000 pounds of gold. But even so, he managed to secure his eastern borders and shift his focus to the west and the lost Roman provinces.

- Extremely Rare Ancient Mosaic Bearing a Greek Inscription Discovered “Miraculously” in Jerusalem

- Theodora: From humble beginnings to powerful empress who changed history

- Justinian Plague probably caused by a bacteria - unknown how it appeared

Gold coin of Justinian I, 527–565, excavated in India probably in the south, an example of Indo-Roman trade during the period. (Uploadalt / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Only a year after, in 533, Justinian launched a campaign against the Vandals of North Africa. Vandals were a Germanic tribe that managed to establish a kingdom in what is today’s Tunisia, and successfully raided through the Mediterranean, even sacking Rome.

The skilled general Belisarius proved his competence in this lighting fast campaign, managing to conquer the Vandals in just a year, after defeating them in two key battles – at Ad Decimum and Tricamarum. The victory resulted in the establishment of the ‘Praetorian Prefect of Africa’ and was the first step towards the restoration of Rome’s lost provinces.

In the very next year, Justinian launched his next conquest, this time aimed at the Ostrogoths, another Germanic tribe, and their kingdom in the Italian peninsula. Known as the Gothic War, this conflict lasted considerably longer than the previous – almost 20 years.

Even though the Byzantines conquered the Ostrogothic capital and effectively the whole Italian peninsula in the first five years of the conflict, it still evolved into a long struggle against King Totila – a struggle that would last for the next 15 years. In the end, Justinian re-conquered Italy, but would subsequently lose large parts of it to the invading Lombards, roughly a decade later. As a result of these wars, the entire peninsula was ravaged, depopulated, and desolate.

Perhaps the last major conflict of Justinian’s rule was the renewed war with the Sassanid Empire. Bolstered by an unexpected revolt in Armenia, as well as urging from Ostrogothic ambassadors, the Persian king Khosrau broke the established ‘Eternal Peace’ and plundered Byzantine territories.

The war dragged on for a few years, without any major accomplishments on either side. In the end, a new deal was struck. Again, Justinian had to pay – this time an annual fee of 30,000 solidi.

The Rise of the Slavs

Even when Justinian managed to reclaim North Africa, Southern Iberia, and Italy, the Eastern Roman Empire still suffered from threats which couldn’t be successfully dealt with. One of the major such incursions was centered in the Balkan peninsula. Ever since the mid 520’s, the Slavs had begun migrating deeper and deeper, eventually crossing the Danube and coming into conflict with the Romans.

By 540, they reached Thessalonica in Greece, as well as Dalmatia, and Adrianople. Slavonic peoples would prove to be one of the biggest opponents of Roman rule.

Emperor Justinian reconquered many former territories of the Western Roman Empire, including Italy, Dalmatia, Africa, and southern Hispania. (Tataryn / CC BY-SA 3.0)

In summary, Justinian only partially managed to achieve his goal of restoring the Roman Empire. After the initial success against the Vandals, the Gothic war dragged on for far too long. These campaigns proved costly for the empire’s coffers, as well as manpower, and this required raised taxes and levies throughout the empire, earning Justinian some enmity with the populace.

Overall, we can see Justinian’s ambitious and confident rule. He was a risk taker, managing to win most of his campaigns even when dangerously over-stretching the resources of his empire.

Justinian’s Final Years and Lasting Impact

Death found Justinian in his 83 rd year. He died childless. A single witness was at his side then and claimed that Justinian’s last act was to name his nephew Justin as his heir. Whether or not this was true, we will never know, but a pre-arranged deal is the most likely option.

During his life, Justinian’s rule had its positive and negative aspects. At the start shaky, it was a target of much animosity, and he had to struggle with the Nika revolt. On the other hand, he issued his judicial reforms, which were highly influential at the time and quickly adopted by many developed kingdoms. He also placed great emphasis on art, literature, and culture, and was an active builder of churches, monasteries, fortifications, and numerous such buildings.

Justinian was also highly interested in theology, and a devout Christian, particularly in his later years. He fought viciously to extinguish paganism once and for all, delivering a series of legislations and laws that prosecuted them, deprived them of property, and all freedom. Today, Justinian the Great is revered as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- The Busy Romans Needed a Mid-Winter Break Too … and it Lasted for 24 days

- Secrets of the Hagia Sophia - Healing Powers, Mysterious Mosaics and Holy Relics

- Making Money Divine: Roman Imperial Coins had a Unique Value in Scandinavian Cultures

Hagia Sophia mosaic depicting the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child on her lap. On her right side stands Justinian, offering a model of the Hagia Sophia. (Myrabella / Public Domain)

Justinian was buried with the highest honors, with a procession leading him to his resting place in his personal mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles. During the sack of Constantinople in 1204, the Crusaders pillaged and robbed the mausoleum and desecrated his remains.

Conclusion - The Legacy of Justinian the Great

During his reign it is clear that Justinian walked a thin line between love and hate. His bold and revolutionary decisions were a clear sign of his visionary nature, but those around him didn’t always appreciate it.

Nevertheless, Justinian brought a somewhat prosperous era to the Eastern Roman Empire, expanding its territories through re-conquest and securing all naval routes. His judicial work and the reforms of all Roman laws were a historic milestone and they are still relevant even today.

But sadly, all that he managed to bring under the canopy of the eastern empire would be gradually lost in the generations after his rule. The golden age in architecture, literature, and art that began in Justinian’s time, would not be experienced for a few centuries afterwards.

All of these things combined, both the loved and the hated, serve to portray Justinian as the ruler that he really was – an ambitious visionary, a skilled man who rose from a family of swine herders to become the emperor of an empire. His rule gave important lessons to those who came after him and his conquest of the Germanic tribes was a catalyst that ushered Europe into a new age, giving birth to new nations and kingdoms. And rightly so, this emperor earned his epithet – Justinian the Great.

Top image: Roman emperor. Credit: Feenstaub / Adobe Stock

References

Baker P. 2002. Justinian, the Last Roman Emperor. Cooper Square Press.

Barker W. 1966 . Justinian and the Later Roman Empire. University of Wisconsin Press.

Cavendish R. 2015. Death of Justinian I. History Today. [Online] Available at: www.historytoday.com/archive/months-past/death-justinian-i

Diehl C. 1920. Histoire de l'empire byzantine. Open Source.

Evans A. 1998. Roman Emperors – Justinian. [Online] Available at: www.roman-emperors.org/justinia.html

Evans A. 2005. The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Empire. Greenwood Press.

Maas, M. (edited). 2006. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press.

Rodgers K. 2013. Justinian I – Byzantine Emperor. Teacher Created Materials.