The Question of Ancient Kings: Cerdic of Wessex, First Saxon King of England?

Historians of the ancient world face a myriad of challenges when studying the past. Centuries of legends and myths become intertwined with recorded facts, leaving behind a complex web of mystery. Such is the case with Cerdic of Wessex. Was he an ancient Saxon conqueror, or a British ealdorman? Did he do battle with King Arthur, or was he the legendary wielder of Excalibur himself? Did Cerdic of Wessex even exist?

Cerdic of Wessex and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Cerdic of Wessex did, indeed, exist. The Chronicle was the first attempt at an official record of English history, written around 890 AD and edited up until 1100 AD. It tells us that Cerdic was a Saxon (referring to people of Germanic descent who occupied central and northern Germany) chieftain who landed at modern-day Hampshire in 495 with five ships full of warriors.

- The Reign of Aethelwulf, King of Wessex: Between Realm and Religion

- King Egbert of Wessex Conquers all to Become Bretwalda, the First King of a United England

By 519, Cerdic and his son, Cynric, had laid claim to swathes of land through a series of battles with the Britons. After his victory at the Battle of Cerdic’s Ford, Cerdic established the Kingdom of the West Saxons (Wessex) with himself as king.

Cerdic is thought to have died in 534, yet his influence lasted for centuries. Some genealogies of the English monarchy claim that every monarch of England except for Canute, Hardecanute, the Harolds, and William the Conqueror descended from Cerdic.

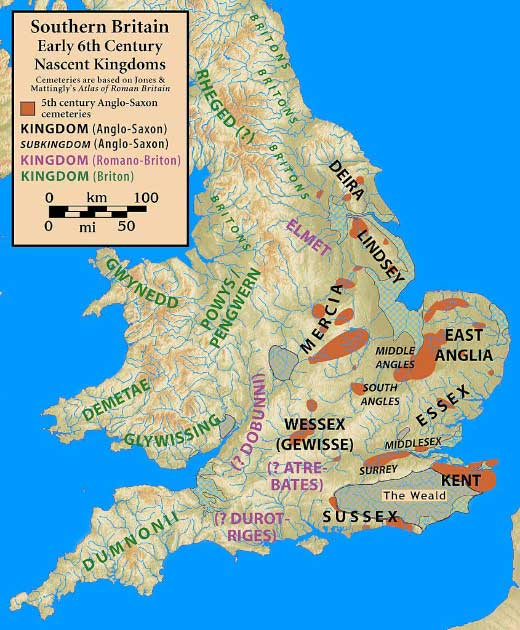

South Britain in the early 6th century, which more or less corresponds to when Cerdic of Wessex lived. (my work / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Cerdic of Wessex: King or Ealdorman?

Here is where the historical record becomes complicated. First, scholars have noted that “Cerdic” is a British name, not Saxon. Additionally, the Chronicle refers to Cerdic and Cynric as ealdormen, not kings. If they were leaders of an invading party from the continent, why the title of ealdormen, which suggests they were appointed officials in some capacity?

Finally, ancient sources differ and conflict in their account of Cerdic’s life, reign, and lineage, and the Chronicle, our primary source of evidence regarding Cerdic, was written 350 years after the events described.

- Aethelred II: Aethelred the Unready, or Was He Just Unlucky?

- King Penda of Mercia: Militant Heathen or Visionary Statesman?

Still, while the accuracy of the record cannot be completely trusted, Cerdic is referenced in numerous works. Additionally, three locations in England bear his name: Cerdicesford, Cerdicesleaga, and Cerdicesbeorg. We can presume that these places were named after an influential person, and that that person was Cerdic.

Theories Regarding Cerdic’s Name

Rodney Castleden, author of numerous well-respected history books, posits that Cerdic may have been a Briton whose family was entrusted by the late Roman Empire to defend a portion of the Saxon Shore (a series of fortifications put in place along both sides of the English Channel). Cerdic may have decided to expand his territory and initiated his invasion from his family’s holding. This would explain the title of ealdormen as well as the British etymology of the name and is supported by the lack of Saxon architecture in the area.

Castleden further argues that Cerdic may have been neither Germanic nor a local of what would later be called Wessex; he may have come from Sussex as an advance party. Cerdic’s arrival along the Southampton coast in 495 coincides with Aelle’s (King of the South Saxons) consolidation of his kingdom and would be a logical strategic maneuver. The name “Cerdic” may have been a nickname given by other residents of Sussex and adopted by Cerdic, as Saxons taking on British names was not unprecedented (Castleden points to Caedbaed, an Anglo-Saxon king who took a British name). But while these are historically logical explanations of some aspects of Cerdic’s aura of mystery, what of his relation to King Arthur?

- Arthurian Legend – Medieval Literature Laced With Truth?

- King Aelle and the Blood Eagle: Ritual Sacrifice in Viking Age Britain

Tapestry showing King Arthur, who is sometimes considered to be the same as Cerdic of Wessex, as one of the Nine Worthies, wearing a coat of arms often attributed to him from circa 1385 AD. (Public domain)

Arthurian Legend and Cerdic, King of Wessex

First, historical consensus is that there is no evidence King Arthur was a real person. The two primary descriptions of Arthur, Nennius’ history of Arthur’s 12 battles and Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the King’s of Britain, are based primarily on poetry or a long-lost manuscript that Monmouth supposedly had access to. Each presents a series of physical impossibilities. For example, Nennius’ 12 battles were so geographically widespread it is unlikely Arthur could have participated in all of them. Additionally, the only surviving contemporary historic record of a battle between the Saxons and Britons (Badon Hills) does not describe Arthur at all. How, then, did Cerdic become involved in the myth and legend of Arthur?

Details regarding the life and exploits of Cerdic are hardly available, which likely lead to historians “filling in the blanks” over centuries of writing. In his 1862 book, The Manual of Dates, George H. Townsend references a battle fought in 520 between Cerdic and Arthur. Yet, if Arthur, who supposedly never lost a fight, won a resounding victory over Cerdic of Wessex, why was Cerdic allowed to conquer so much territory and establish a kingdom? While much of Arthur’s supposed life is shrouded in total mystery, at least portions of Cerdic’s are accepted as fact, including his successful invasion of the Isle of Wight in 530, just a few years after he was supposed to have been defeated by Arthur. Thus, even if Arthur existed, it seems highly unlikely the two ever met on the battlefield.

"The King Carados" (in blue at front), who is connected to the name Ceredig Vreichvras or Cerdic of Wessex, sits at the Round Table during the appearance of the Holy Grail in a 15th-century miniature by French artist Évrard d'Espinques. (Évrard d'Espinques / Public domain)

Are Cerdic and King Arthur One in the Same?

Historians John and Joseph Rudmin noted a number of similarities between the Arthur of legend and the Cerdic of history (who they posit was also known as Ceredig Vreichvras). They examined several writings regarding both figures and created a table comparing them side-by-side, revealing striking parallels. The paper makes for fascinating reading and argues that King Arthur and Cerdic were actually the same person, which the authors claim resolves a number of the problems surrounding Arthur’s potential presence in history. Others, however, have pointed out that these conclusions rest on the shaky foundations of assumption and lack the kind of hard historical evidence necessary to draw a firm conclusion.

Ultimately, modern historians must grapple with the fact that history has often been used as a political tool. For centuries (and yes, even today) historical narratives served to bolster nationalism, to push political ideals, to boost the reputation of leaders, or to minimize dark deeds.

This fact, when combined with the often ill-recorded details of the ancient world, leads to figures like King Arthur and Cerdic of Wessex, people shrouded in mystery whose lives were mythologized by successive chroniclers of history weaving stories to suit their needs.

We may never know the actual truth of who Cerdic was, why he was so influential, or whether he may have inspired Arthurian legend, but to be honest, the mysteries of history are half the fun.

Top image: An imaginary depiction of Cerdic of Wessex from John Speed's 1611 "Saxon Heptarchy." Source: John Speed / Public domain

By Mark Johnston

References

Bradbury, J. 2004. The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Taylor and Francis Group.

British Library. n.d. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 11 th Century. Available at: http://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item126532.html.

Castleden, R. 1999. King Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend. Taylor and Francis Group.

History.com. n.d. Was King Arthur a Real Person? Available at: https://www.history.com/news/was-king-arthur-a-real-person#:~:text=But%20was%20King%20Arthur%20actually,confirm%20that%20Arthur%20really%20existed.

Johnson, B. n.d. Kings and Queens of Wessex. Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Kings-Queens-of-Wessex/.

Mark, J. n.d. Cerdic. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Cerdic/.

Rudmin, John C. and Joseph W. n.d. Arthur, Cerdic, and the Formation of Wessex. Available at: https://levigilant.com/Bulfinch_Mythology/bulfinch.englishatheist.org/arthur/Caradoc-Vreichvras.htm.