The Celestial Monsters and Demonic Wizards Of The French King’s Surgeon, Ambroise Pare

Sometimes we lie in bed at night and think about our increasing mortgage repayments, getting that new car, or that idiot beside you at work, but there was a time in all of our lives when we lay there, eyes peeking over the duvet, frozen stiff with utter terror at the prospect of a monster in the cupboard, or one climbing out of that trap door beneath your bed, that you could never find, but knew was there. Monsters. Where on Earth, or otherwise, did they come from?

Finding Monsters with Monstrophy

Fictional literature and films have made several monsters famous, including Count Dracula, Frankenstein's monster, zombies, werewolves, and mummies. But in the real world, the academic study of monsters and their place in history is known as monstrophy. The word ‘monster‘ is derived from the Latin monstrum, meaning "portent, unnatural thing/event regarded as omen/sign/portent” and it was usually associated with something morally wrong or evil and sometimes it was used to describe physical or psychological abnormalities, or a person who does cruel or horrific things.

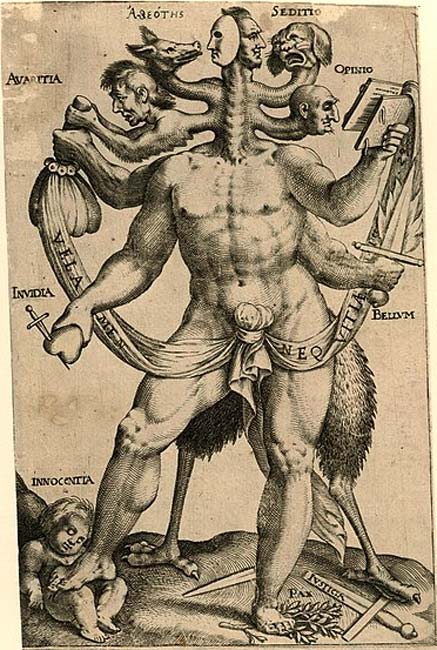

A polemical allegory presented as a five-headed monster, 1618. Monsters often gave artists a platform to express deeply esoteric concepts. (Public Domain)

Historically, accounts of monsters were often of composite creatures and hybrids of humans and animals. And although they pre-date written history, monsters have their origins in society's literary and cultural heritage. The 16th century saw an increase in international shipping and with returning ships so too came sightings of new monsters. The expansion of the sciences due to the Renaissance brought about numerous new natural history discoveries from all around the world and scientists and nobles began keeping cabinets of curiosities exhibiting precious stones, fossils, skeletons, antiques, works of art, and stuffed animals, etc.

- Outlaws, trolls and berserkers: Meet the hero-monsters of the Icelandic sagas

- Titanoboa: The Monster Snake that Ruled Prehistoric Colombia

- 1,400-Year-Old Tomb with Bizarre Images of a Blue Monster Found in China

A corner of a cabinet, painted by Frans II Francken in 1636 reveals the range of connoisseurship a Baroque-era virtuoso might evince. (Public Domain)

Ambroise Paré’s Monsters and Wonders

Ambroise Paré (c. 1510 – 1590) was a French barber surgeon who was a part of the Parisian Barber Surgeon Guild and served kings Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. He invented several surgical instruments and was also a keen anatomist. To some, he is considered one of the fathers of modern forensic pathology and a pioneer in surgical techniques, battlefield medicine, and the treatment of wounds.

Besides being a medical professional, Paré was very much interested in monsters and his 1580s book ‘Monsters and Wonders’ is an illustrated treatise of the monsters he claimed to have observed himself as well as those drawn from his many readings. It was written to quench the thirst of curio collectors and those with a taste for the supernatural.

Ambroise Paré (ca. 1510-1590), famous French surgeon; Posthumous fantasy portrait. (Public Domain)

The end of the Renaissance was a time of many esoteric beliefs and a fascination with unexplainable phenomena and all things supernatural. In his introduction to the 1971 edition of ‘Monsters and Wonders’ , writer Jean Céard distinguished the three main sources of Ambroise Paré’s work:

- Stories of Boaistuau and Tesserant (1567).

- Five Books of the Deception and Deception of the Devil by Jean Wier (translated 1567).

- Three books of the apparitions of the spirits of Ludwig Lavater (trans 1571).

Human Monstrosities, Animal Monsters, Demons, and Sorcerers

The first writer is thought to have inspired Paré's chapters on “human monstrosities” and “animal monsters” and the other two provoked his notes on “demons and sorcerers”, but Paré does not distinguish reliable sources from the imaginative and was subsequently accused of plagiarism in that he practically copied whole sections from these books without editing a word.

‘Monsters and Wonders’ consists of thirty-eight chapters illustrated with seventy-seven woodcuts of two types of monster. In a very short preface, Ambroise Paré defines monsters as "all things that appear in addition to the course of Nature" and then describes a child with two heads and said, "things that come against nature all at all" and he then gives another example of a woman giving birth to a snake or a dog.

In chapter one, Paré gives "thirteen cause of the appearance of monsters and wonders” then lists “accidental diseases” and gives some examples of monsters, including “magical demons” and more recognizable beasts like the whale, which according to Paré was a "big fish monster.”

St. Brendan's ship on the back of a whale, and his men praying, in Honorius Philoponus' Nova typis transacta navigation 1621; image from Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps by Chet Van Duzer. (Public Domain)

In chapter 19, Paré gives examples of monsters created by "seed mix“ and from chapters 25 to 33 the treatise refers to “wizards and demons." In the final section he lists "astronomical monsters" and "monstrous things” like volcanism and earthquakes. The most monstrous “thing” is said to be underwater volcanism. The last chapter, chapter 38, focuses on astronomical monsters and astronomy focusing on the latent divine harmony within the world.

Ambroise Paré put animals, stars, and humans on the same plane to represent the diversity of the natural world. And his bringing together of human diseases with part-human part-animal creatures as well as with sorcerers and exotic animals celebrates the perceived divine powers and harmony of the whole world. As can be expected, such claims bring with them their critics, and Paré had many.

In the 16th century mostly all scholarly documents were written are in Latin and Paré wrote ‘Monsters and Wonders‘ in French, which really upset the medical community. Not so much because of all the monsters, wizards, and demons, but because he commercialized his work and made it accessible to a wider audience at a time when doctors and surgeons liked to keep their valuable knowledge within their tightly knit circle.

The Monsters of Ambroise Paré

The first category in ‘Monsters and Wonders’ describes “human monsters" and “appearances anomalies” which he related to pathological disorders. For example, he included a figure of two twinned females joined and united by the posterior parts. He noted beside this image “It is also the litters of several children, not only twins but on bisexuality: Children of two sexes or a couple of two androgynous children being joined back to back, one with the other.” In another entry he described a "Pregnancy with 11 fetuses.”

This illustration of a ‘Pregnancy with 11 fetuses’ is a copy of an original by Ambroise Paré from the 1900 edition of ‘Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine’. (Public Domain)

He then described monsters that had been born “half of a beast's figure, and the other human,” for example “a pig with the head and face of a man, similarly hands and feet, and the rest like a pig.” Next, he listed “fabulous animals” and sub-series like ‘exotic animals’ and ‘terrestrial monsters’ in which he described “An African chameleon, endowed with wonderful properties and a beast called Huspalim, “big and very monstrous, with scarlet-red skin, round head like a ball, round, flat feet without offensive nails.”

- Aspidochelone: A Giant Sea Monster of the Ancient World and an Allegorical Beast

- Of Monsters and Men: What Is the Grim Being Known as Grendel from the Epic Beowulf?

- Where the Wild Things Are: Garden of Monsters Was Built to Convey the Despair of its Creator

Wood cut from ‘Monsters and Wonders’ depicting the legendary Huspalim. (Wassawan V./CC BY SA 4.0)

Under the section ‘volatile monsters’ he added the portrait of a bird of paradise, but without feet and with a beak and body more similar to the swallow, but adorned with various feathers. ‘Sea Monsters’ were given a long chapter with illustrations of monstrous flying fish and a new species of whale.

Finally, ‘celestial Monsters’ were perceived as “those who represent grace and the spell.” According to Paré “The sea is the prodigious pool that inhabits the fertile belly of the sea, mirror of the earth and inexhaustible reserve of vitality.” The last two chapters describe the psalmist who evokes "the whale, horrible monster and great” and he inserted a portrait of a Triton and a Mermaid on the Nile River in Egypt.

Portrait of a Triton and a Mermaid on the Nile River. Ambroise Paré from the 1900 edition of ‘Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine’. (Wassawan V./CC BY SA 4.0)

Top Image: ‘Ambroise Paré and the examination of a patient’ by James Bertrand. Source: Ji-Elle/CC BY SA 3.0

By Ashley Cowie

References

Allchin, Douglas, (2007), Monsters & Marvels: How Do We Interpret the “Preternatural”?". US: The American Biology Teacher, November. p.565.

Banerjee, Anirban Deep; Nanda, Anil, (April 2011), Ambroise Paré and 16th century neurosurgery. UK: British Journal of Neurosurgery. 25 (2): 193–196.

Jean-Pierre Poirier, (2006), Ambroise Paré, Paris, p. 42.