The Eye-opening Epitaph of Allia Potestas and her Perugian Ménage à Trois

The epitaph of Allia Potestas gives an intriguing insight into the sexual mores of the ancient Romans. The tombstone of this ex-slave from the town of Perugia contains fascinating details about her daily life, loves, and sexual exploits.

The inscription has puzzled scholars for years and has been described as a “curious, touching, delightful text, very difficult in places, even gently titillating,” according to Nicholas Horsfall in his article Allia Potestas and Murdia: Two Roman women. He adds: “Epitaphs constitute some of our most important evidence for the status of women and for attitudes towards them.”

Roman women in ‘ The Frigidarium’ (1890) by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Public Domain)

Who Was Allia Potestas?

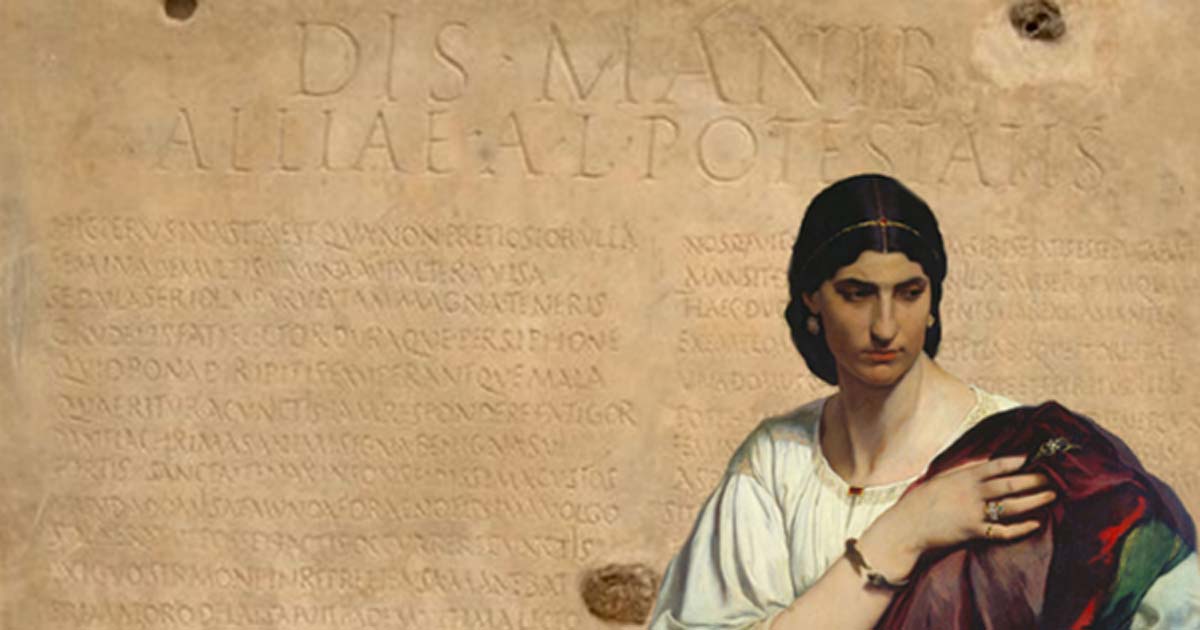

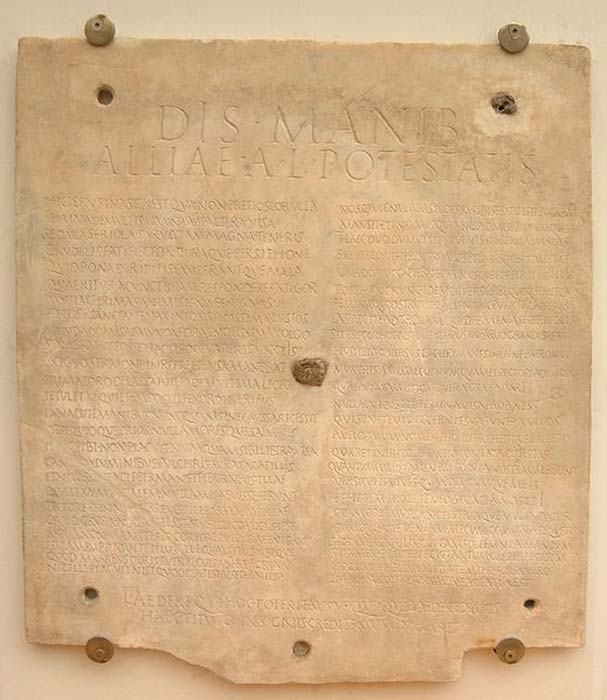

So, what does the epitaph tell us about the personality of the ex-slave who seemed to live life to the fullest? At the top of the marble tablet are the words “To the Di Manes of Allia Potestas, freedwoman of Aulus.” It’s probable that Aulus Allius freed her, had the stone erected in her honor, and lived with her as his concubine.

There is controversy surrounding the exact dating of the tombstone. At first, it was dated to the 3rd–4th centuries AD on paleographic grounds. However, stylistic and linguistic analysis suggests a more likely date is the 2nd century AD.

- Roman Engagement and Wedding Rings: Joining Hands and Hearts

- Mighty Cartimandua, Queen of the Brigantes Tribe and Friend to Rome

- Bellona: The Roman Goddess of War and Artistic Muse

The 50-line epitaph, which is written in verse, is divided into three sections and tells us about this unusual woman. Praise for Allia is pretty standard fare at first and it suggests she aligned to all the mores of what was required of a respectable Roman woman.

Sepulchral inscription of Allia Potestas (1st–4th century AT), found on a marble tablet in Via Pinciana, Rome, Italy in 1912. (Kleuske/CC BY SA 3.0)

Aulus Allius says Allia Potestas kept busy from morning until night and was also skilled in the most essential of feminine traits, spinning. She was "always the first to rise and the last to sleep... with her woolwork never leaving her hands without reason", reads the epitaph.

There is no doubt that this is a love match, as Aulus, the bereaved partner, mourns Allia’s passing and says she will be remembered by him, vowing that she “shall live as long as may be possible through [his] verses."

Ménage à trois

So far, all appears stereotypical. But amongst the platitudes is the revelation that Allia Potestas was living in a ménage à trois with two men. The woman was a devotee of polyandry, living with “her two young lovers”, which the epitaph writer likens to “the model of Pylades and Orestes.”

Orestes was sent to Phocis, an ancient region in the central part of Ancient Greece, during his mother Clytemnestra's affair with Aegisthus. There he was raised with Pylades, son of King Strophius , and thought of him as a brother. Pylades later convinced Orestes to follow through with his plan to avenge his father Agamemnon’s death and kill Clytemnestra.

Orestes, Pylades and Electre at the tomb of Agamemnon. Campanian red-figure hydria, ca. 330 BC. (Public Domain)

There’s an added sexual dimension to the relationship between Orestes and Pylades, who were “also frequently described in antiquity as same-sex lovers,” according to Anise Strong in her book Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World. Whether Aulus Allius and the unnamed other male lover were also in a sexual relationship remains open to speculation.

Aulus goes into unusual erotic detail about his deceased female partner. He wrote how Allia "kept her limbs smooth" and that "on her snow-white breasts, the shape of her nipples was small." She was “beautiful with her generous body” and “she sought out every hair.” It’s interesting to note that Allia was vain and scrupulous in depilation, so that her skin was smooth, not so very different from the beauty routines of the modern day.

Fresco showing a woman looking in a mirror as she dresses (or undresses) her hair, from the Villa of Arianna at Stabiae (Castellammare di Stabia), 1st century AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum. (Carole Raddato/CC BY SA 2.0)

Breaking Sexual Conventions

One of the most prominent admirers of this second-century AD woman is Professor Mary Beard, who chose Allia as one of the most intriguing characters in Roman history, visiting her tombstone at the Museo Nazionale Romano during her BBC series Meet the Romans. Beard says Allia deserves to be much more famous than she is for her importance in revealing the nature of sexuality in ancient times. “If you wanted just one example of how Roman relationships could be as murky and as messy and as mixed up as our own, it would have to be the household of Allia Potestas.”

Professor Beard is full of admiration for this extraordinary woman and her household, which gives a “very different view on Roman virtue and fidelity.”

The Cambridge classics professor says with characteristic frankness: “I love the story of Allia Potestas, the ex-slave who was living with two blokes.” The tantalizing few details we have of her are described by Beard:

“She was not posh, and probably an ex-slave, and the epitaph describes her body in uncomfortable detail (right down to her lovely nipples), but it also insists that she was a perfect housewife. She was always up before her lovers and always in bed later (getting the housework done); unsurprisingly, she had rough hands. It’s a wonderful mixture of erotic fantasy and domestic drudgery.”

Fresco depicting a seated woman, from the Villa Arianna at Stabiae, 1st century AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum. (Carole Raddato/ CC BY SA 2.0 )

A Harmonious Household

Aulus Allius seems not to have been troubled by jealousy; after all, he was sharing Allia’s bed with another man. This is very far removed from the ideal Roman matron, the univira (a one-man woman), according to Roman Civilization: Selected Readings. Volume II: The Empire.

It’s possible that threesomes in the ancient world were not particularly unusual. In Pompeii, a wall painting on a changing room in the baths, dated to around 79 BC, shows two men and a woman having sex.

However, the domestic arrangement, which we assume was harmonious during Allia’s lifetime, was not destined to last beyond her death, with the two men parting company. As the inscription sadly informs: “But now that she is dead, they will separate, and each is growing old by himself.”

Two men and a woman making love; Pompeian wall painting, from one of the Therms (baths), the south wall of the changing rooms - painted around 79 BC. (Public Domain)

There are other interesting anomalies in the text. Aulus describes his dead lover as “chaste” in the epitaph, despite her having two lovers. Perhaps this word meant something different in the ancient world than it does today?

- Skin Color Didn’t Matter to the Ancient Greeks and Romans

- Swans Fat, Crocodile Dung, and Ashes of Snails: Achieving Beauty in Ancient Rome

- A Failed #MeToo Moment: Just How Horrible Being An Ancient Roman Actress Could Be

The freedwoman is also described as “very well known to the crowd”, which is not the mark of a respectable Roman woman, who would not usually be seen in public spaces. But then Allia seems to have been living an unconventional lifestyle. Nonetheless, it is comforting to discover that some women in ancient times escaped the confines of the home and enjoyed moving with freedom in the forum and market places of ancient Rome.

‘Roman Fish Market. Arch of Octavius’ (1858) by Albert Bierstadt. (Public Domain)

The epitaph undoubtedly sheds light on the day-to-day existence of ordinary working men and women in ancient times. However, there is a caveat. The words coming down to us from centuries ago are from the male perspective of the writer, Aulus Allius. It would have been even more eye-opening to know what the female subject of the tombstone would have said. As Beard muses: I can’t help wondering what Allia Potestas’ version of the story about these guys would have been.”

Top Image: ‘Half-Length Portrait of a Roman Woman’ (1862/1866) by Anselm Feuerbach. (Public Domain) Background: Sepulchral inscription of Allia Potestas (1st–4th century AT), found on a marble tablet in Via Pinciana, Rome, Italy in 1912. (Kleuske/CC BY SA 3.0)

References

Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World by Anise Strong. WLGR

Ancient inscriptions in the limelight. https://www.eagle-network.eu/story/putting-ancient-inscriptions-in-the-limelight/

Mary Beard’s BBC blog. http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/tv/entries/5271d4d8-cfac-3eb4-b3b1-c9ec174c8b6e

Love, sex and marriage in ancient Rome. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201206/love-sex-and-marriage-in-ancient-rome

Alastair J.L. 2010, Blanshard, “Roman Vice,” in Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity

Commentary on the epitaphs of Allia Potestas. http://iris.haverford.edu/allia-potestas/inscription/