The Deadly Victoria Hall Stampede Tragedy

The Victoria Hall Stampede was a tragedy that occurred in Sunderland, in the northeast of England, in 1883. The unfortunate incident happened in a concert hall at the end of a children’s entertainment show. During the stampede, a total of 183 children were crushed to death.

The Victoria Hall Stampede is considered to be the worst tragedy of its kind in British history. The whole country was moved by the terrible event, and there was a nation-wide outpouring of grief at that time. Lots of people gave donations to the town and a statue was erected in memory of the children who lost their lives.

In recent times, annual memorial services have been held to mark the day of the tragedy and to remember the victims. One of the positive developments following the Victoria Hall Stampede was the invention of the push bar (known also as the crash bar or panic bar) emergency door.

The History of Victoria Hall

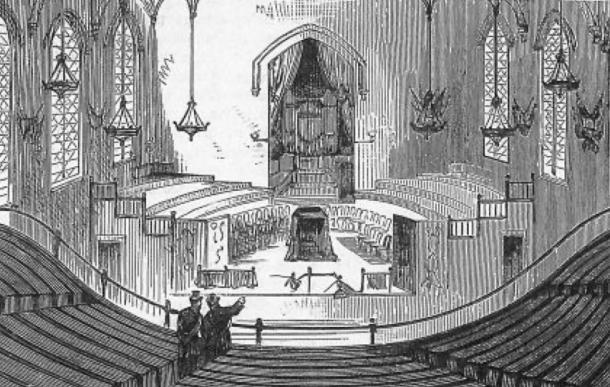

Victoria Hall stood in the city of Sunderland, on the corner of Toward Road and Laura Street, on the east side of Mowbray Park. The building, which is a concert hall, was built in 1872. Victoria Hall was an ambitious project, built to mimic the size and architectural style of the Crystal Palace and Albert Hall (both in the capital, London).

Victoria Hall as an imposing brick building built in the Gothic Revival (known also as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) style, which was in vogue during that period. The construction of Victoria Hall was funded by a Quaker minister by the name of Edward Backhouse and cost $10,500 (£9,500). It seems that either the money, time, or both, had run out as a difference is seen between the north and south gable walls.

While the latter was partially hidden by the end of the terrace houses it adjoined, the former was exposed for all to see. As it was a plain brick wall, it was not a particularly beautiful thing to look at and was even regarded as an eyesore.

Victoria Hall - funded by Edward Backhouse and built in 1872. (sunderland.yolasite / Public Domain)

Inside Victoria Hall, there was seating on the ground floor, in a dress circle on the first floor, and in the gallery above. The building could seat up to 3,000 people and therefore was a popular venue for public meetings and entertainment. Unfortunately, few records of the meetings and events held at Victoria Hall have survived till this day.

- Fighting the Flaming Wrath - The Great Fire of London, 1666

- Repaired With Duct Tape And Bubble Gum? A Section Of The Great Wall Of China Collapses

- Forgotten Disaster: The Great London Beer Flood That Killed Eight People

The stage of Victoria Hall, as seen from the gallery. (sunderland.yolasite / Public Domain)

Nevertheless, considering that its benefactor was a Quaker minister, one can reasonably speculate that these events adhered to the strict temperance and religious codes of the Quakers. Victoria Hall would probably have remained merely as an example of Victorian architecture and forgotten by history had it not been for the tragic incident that occurred in 1883.

The Disastrous Victoria Hall Event

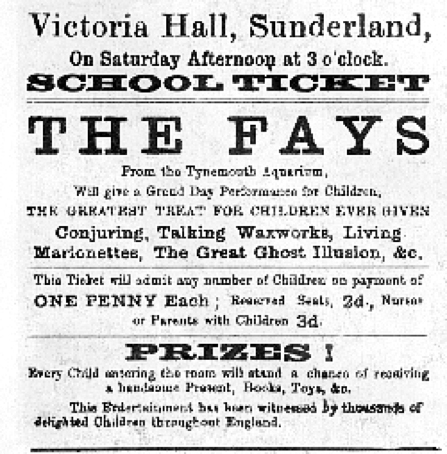

The Victoria Hall Stampede occurred on the 16th of June 1883. On that fateful Saturday, Victoria Hall served as the venue for a performance put on by the Fays, a pair of traveling entertainers from Tynemouth Aquarium.

According to a ticket from the show, the Fays “Will give a Great Day Performance for Children”, which consisted of “Conjuring, Talking Waxworks, Living Marionettes, The Great Ghost Illusion, etc.” Moreover, it was promised that “Every child entering the room will stand a chance of receiving a handsome present, books, toys, etc.”.

Finally, the Fays boasted that “this entertainment has been witnessed by thousands of delighted children throughout England“. They were probably expecting, like everyone else, that the performance at Victoria Hall would not be unlike their previous ones. Unfortunately, Mr. and Mrs. Fay were wrong.

Poster advertising the 1883 variety show at Victoria Hall. (Elysium 73 / Public Domain)

At three o’clock in the afternoon, Victoria Hall was packed with some 2,000 children who were eager to watch the performance provided by the Fays. The show seems to have gone off without a hitch, but tragedy struck as it ended.

As the performance concluded, it was announced that children with curtained numbered tickets would be given prizes as they left the concert hall. At the same time, prizes were being given out to the children on the ground floor. It seems that the latter was done in a rather disorderly fashion, as the prizes were thrown out into the audience.

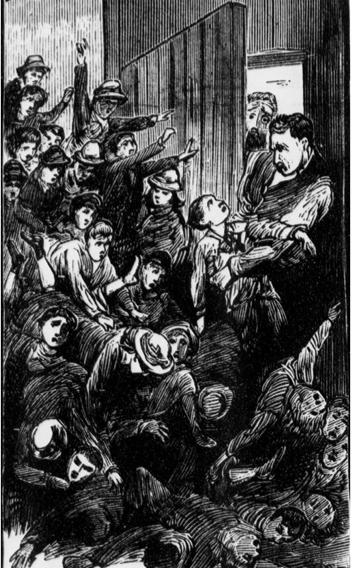

The children on the first floor and gallery above, who were witnessing the scene happening on the ground floor, became anxious that they would miss out on the free prizes. Therefore, many of them began to make their way down to the ground floor of the concert hall. It is estimated that there were as many as 1,100 children seated in the two upper levels.

At the foot of the stairwell was a door that provided access to the ground floor. On that day, the door was opened inwards and bolted by the management, leaving a small opening of about 20 inches (50 centimeters) for the children to pass through. This arrangement allowed for children to exit the stairwell, and enter the ground floor one at a time, and was meant to control the flow of children, as well as to allow the management to check the children’s tickets more easily.

A few of the children in the front were able to get through the gap in the door but then someone got jammed. As a consequence of the gap being blocked, the children who were immediately behind began to pile one on top of the other.

The pile of bodies, it was reported, reached 20 deep. The children at the top of the stairs, being unaware of what was going on at the foot, continued to surge forward, further crushing and suffocating those trapped in the front.

Image taken from the French paper, Le Journal Illustre depicting the terrible scene at Victoria Hall. (sunderland.yolasite / Public Domain)

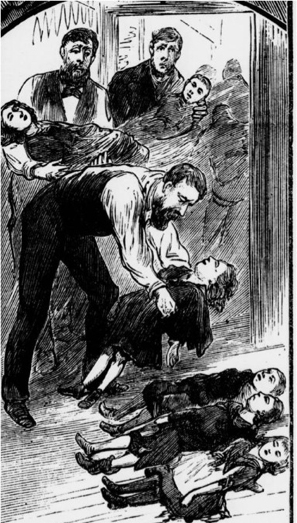

Frederick Graham, the caretaker, tried to untangle the mass of trapped children, but found that the weight far too heavy for him to lift. Thinking on his feet, Graham ran up another stairwell and succeeded in leading about 600 children to safety via another exit.

Around the same time, the adults on the ground floor realized that there were children trapped behind the door and began to do something about it. They started pulling the children one by one through the door. As more adults came to help, the stairwell was successfully cleared in half an hour.

- Here is What it Would Have Been Like to be Caught in the Great Fire of London

- Why Were The Shrove Tuesday Riots So Brutal?

- Researchers Study Mysterious Deaths in Mass Grave at Ancient Haft Tappeh

The staircase calamity at Victoria Hall as adults attempt to pull children to safety. (sunderland.yolasite / Public Domain)

The Victoria Hall Stampede Aftermath

It was only when order was restored that the scale of the tragedy became clear. A total of 183 children, 114 boys and 69 girls, lost their lives that day. The youngest victims of the Victoria Hall Stampede, Dorothy B. Buglass and Margaret Thompson, were only 3 years old, while the oldest, Annie Redmond, was 14.

All the children died of asphyxia. Some families lost all of their children, while the entire Bible class of a local Sunday School lost all of its 30 students during the tragedy.

One survivor of the Victoria Hall Stampede was William Codling Jr., from whom we have an first-hand account of the incident. Codling was born in 1876 and would have been six or seven years old went he attended the performance at the Victoria Hall in 1883. His account of the Victoria Hall Stampede was written in December 1894, 11 years after the incident.

Nevertheless, this account provides a vivid description of what happened that day, from the eyes of a child attending the performance. Codling’s eye-witness account of the tragedy’s aftermath is as follows:

“Then the pressure above began to lessen, a report spread that the toys were being distributed in the gallery and those behind having made a feeble rush upwards, back we tottered across that path of death. At the first landing we were met by some men and taken out of doors into the open air, where was assembled a crowd of frightened people drawn together by wild rumors. Soon men began to come down the steps bearing in their arms lifeless burdens, and from the crowd came a wail of grief, while some of them ran off to tell the terrible news which unnerved the whole town, and which in a few hours sent a thrill of horror through the whole of Britain. I had not thought the affair was serious and now I looked on spellbound as body after body was brought out and laid in a row upon the pavement. One woman, I remember, came out carrying a child which she had gone in to seek while behind her came a sympathetic man bearing another. The woman came down the steps with agonized face and disheveled hair and shouted fiercely to the crowd “Get back! Get back! and let them have air.” “Ah! my good woman,” said the man who bore her other burden, while tears rolled down his cheeks, “Ah! they will never need air more.””

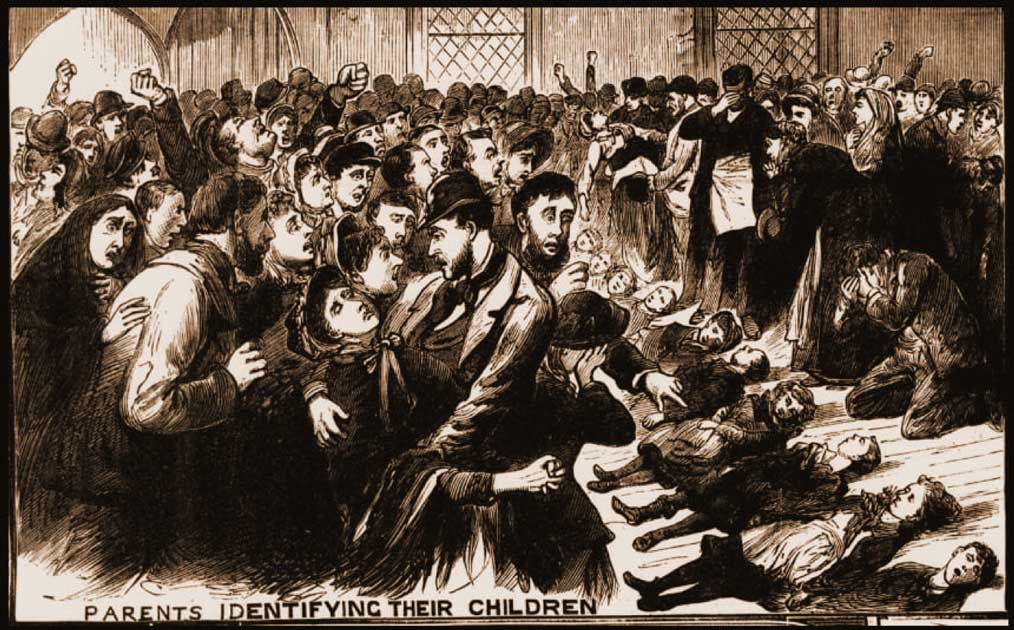

Laying out of the bodies after the Victoria Hall Stampede. (sunderland.yolasite / Public Domain)

Indeed, news of the tragedy spread around the country and was reported by the national newspapers. The whole country was moved by the tragedy and many sent donations to the town. By the 14th of August, a total of $6,404 (£ 5,769) had been collected. One of these donors was Queen Victoria herself, who made a donation of $55 (£ 50).

The queen also asked to be kept informed about the recovery of the survivors and sent a message of condolence to the families who were affected by the tragedy. This was sent to the town’s clergymen, who relayed the message during the subsequent funerals and services. The funerals lasted from Tuesday to Friday, and during this period, all businesses in Sunderland remained closed as a mark of respect.

The donations received were used primarily to cover the cost of the funerals and the remainder was used to erect a memorial statue for the victims. This marble statue was sculpted by W.G. Brooker and depicted a grieving woman with a dead child on her lap, inspired by a Classical statue of Niobe. Originally, there was an inscription on the front of the pedestal. This was later copied onto a tablet, which lies today at the foot of the memorial.

The inscription reads as follows, “ERECTED TO COMMEMORATE / THE CALAMITY WHICH TOOK PLACE / IN THE VICTORIA HALL SUNDERLAND / ON SATURDAY 16TH JUNE 1883 / BY WHICH 183 CHILDREN LOST THEIR LIVES”.

The memorial to the victims of the Victoria Hall disaster, Sunderland, UK, 1883. (Baraliner / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Initially, the memorial stood under a canopy in Mowbray Park, opposite the scene of the disaster. Later on, it was moved to Bishopwearmouth Cemetery, but brought back to Mowbray Park in 2000, with a new canopy. In 2017, the memorial was vandalized, as a panel in the glass case housing it was smashed.

Apart from the statue, the victims of the Victoria Hall Stampede have been commemorated in other ways as well. For instance, a poem entitled ‘ The Sunderland Calamity’ was written by the Scottish poet William McGonagall, who, incidentally, is commonly considered to be the worst poet in the history of the English language.

In more recent years, a memorial service for the victims of the Victoria Hall Stampede is held each year on the 16th of June. This service is organized by the Sunderland Township Heritage Society. In addition, a Sunderland artist by the name of Lyn Killeen paid tribute to the victims of the tragedy through her works of contemporary art, Ascension, and Silent Voices, which were on display at Frederick Street Gallery on the 15th and 16th of June this year.

Lastly, practical measures have also been taken to prevent such a tragedy from happening again. One of the consequences of the Victoria Hall Stampede was the passing of laws in parliament requiring all places of public entertainment to have sufficient exits and that all exit doors must open outwards and be easy to open. Another positive outcome of the tragedy was the invention of the push bar.

The inventor of this door opening mechanism was Robert Alexander Briggs, who was 15 years old at the time of the Victoria Hall Stampede. The push bar was invented some years after the tragedy, and Briggs applied for a patent for his invention on the 7th of November 1891. On the 13th of August 1892, Brigg’s application was accepted and the description of his invention, which is entitled ‘ Improvement in Bolts and Fastenings for Doors of Theatres and other Public Buildings' (GB18871/1891), is as follows,

“The bolts on the door are connected by means of levers or cranks or a combination of levers and cranks with a push piece or push rod contained in a box affixed to the stile of the door so that in the event of pressure on the inside being applied to the push piece or push rod the bolts are automatically withdrawn from the door head and sill and the doors set free. The reverse action shoots the bolts and thoroughly secures the door.”

Top image: The scene at Victoria Hall, the grief-stricken parents having to identify the bodies of their children. Source: wearsideonline / Public Domain

By Wu Mingren

References

devastatingdisasters.com. 2019. Victoria Hall Crush – 1883. [Online] Available at: https://devastatingdisasters.com/victoria-hall-crush-1883/

Eveleth, R. 2013. 183 Children Died in a Stampede for Toys in 1883. [Online] Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/183-children-died-in-a-stampede-for-toys-in-1883-173637/

Hunt, C. 2019. McGonagall Online, The Sunderland Calamity. [Online] Available at: https://www.mcgonagall-online.org.uk/gems/the-sunderland-calamity

Lovell, P. 2019. Robert Alexander Briggs and the invention of the Panic Bolt. [Online] Available at: http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/RobertBriggsPanicBolts.htm

Pears, B. 2019. Victims of the Victoria Hall Calamity. [Online] Available at: https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/DUR/Sunderland/VictoriaHall

Seagull City. 2019. Seagull City: Sunderland's Literary and Cultural Heritage. [Online] Available at: https://wp.sunderland.ac.uk/seagullcity/victoria-hall-disaster/

Sunderland Echo. 2019. Memorial service takes place for victims of Sunderland's Victoria Hall disaster. [Online] Available at: https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/people/memorial-service-takes-place-victims-sunderlands-victoria-hall-disaster-149115

Sunderland Echo. 2017. Memorial to 183 Sunderland children who died in Victoria Hall Disaster smashed up by vandals. [Online] Available at: https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/memorial-to-183-sunderland-children-who-died-in-victoria-hall-disaster-smashed-up-by-vandals-360437

Sunderland Echo. 2019. Remembering a generation of lost children. [Online] Available at: https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/people/remembering-generation-lost-children-74238

Sunderland Echo. 2017. Smashed case which houses tribute to 183 dead children in Sunderland to be repaired. [Online] Available at: https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/smashed-case-which-houses-tribute-to-183-dead-children-in-sunderland-to-be-repaired-360370

Sunderland Echo. 2017. Sunderland falls silent to remember 183 children killed at Victoria Hall disaster. [Online] Available at: https://www.sunderlandecho.com/news/sunderland-falls-silent-to-remember-183-children-killed-at-victoria-hall-disaster-356886

Sunderland Museum and Winter Gardens. 2014. V ictoria Hall Disaster Toy Rocking Horse. [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/4gVnbOcJTOG0qJLYxnA9rw

sunderland.yolasite.com. 2019. Victoria Hall Disaster, 16th June 1883. [Online] Available at: http://sunderland.yolasite.com/vichallstory.php

vads. 2019. Victoria Hall Tragedy Memorial. [Online] Available at: https://vads.ac.uk/large.php?uid=75132

www.durhampast.net. 2019. The Sunderland Project : Remembrances of the Victoria Hall Disaster 1883. [Online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20070724030952/http://www.durhampast.net/sunderland_victoriahall.htm

Comments

Hi Wu,

I just watched a 26 minute documentary on ytube about this very tragedy. Oddly I hadn't noticed the year this happen till reading your article which was 1883.

Why does 1883 stand out too me the most? Krakota it erupted in 1883, I thought back in May of 1883 the volcano began talking but, the Full Eruption took place I think in August.

Getting back to article it was just as horrific to read about this tragic event as too watch it on the Black and white documentary I saw on ytube, so thank you for sharing until next time Goodbye Wu!