The Swiss Pikemen: Europe’s Most Deadly Middle Age Military Formation!

The medieval pike, around 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) in weight and just under 5 meters (16.4 feet) in length, was a weapon supposedly invented in Turin, Italy in 1327 AD. However, its history was actually far longer, and stretched back to the ancient times of Phillip II, the father of Alexander the Great, when Macedonian infantry dominated the battlefield wielding a sarissa, a long spear 4 to 7 meters (13 to 23 feet) in length. Over a thousand years later in 1315, the peasants of Schywz, who were part of the Swiss Confederation, would re-discover this ancient weapon, heroically fending off the armored knights of Leopold I of Austria with nothing but pikes. Going against all the odds, it was one of the first times ever that dismounted commoners had won against the onslaught of armored horsemen, and their victory sent shockwaves throughout Europe as a result. However, it would take over a century more, and a great tragedy, for the Swiss to finally realize the superiority of the pike, which would transform them into the most elite and sought-after warriors of the Middle Ages: the Swiss pikemen.

It took a long while for the Swiss pikemen to be a force of nature. In the 1386-AD Battle of Sempach, painted here by Karl Jauslin, the Swiss lost because the other side had long pikes that effectively made the halberd spear-axe inferior. And it was a few more years before they understood the power of the pike! (Karl Jauslin / Public domain)

Origins of the Swiss Pikemen: The Disaster of Arbedo

With the Habsburgs, (ruling family of the Holy Roman Empire from 1438-1740) distracted by their eastern conquests into Austria, Hungary, and Bohemia, the Swiss Confederacy attacked the empire’s forces at Sempach in a bid to expand their territories. At the Battle of Sempach in 1386, the Swiss armies, armed primarily with halberds (a combined spear and battle-ax), faced off against Habsburg troops, whose dismounted knights brandished longer lances or pikes to hold off the Swiss hordes to great effect. Thousands of Swiss infantrymen were killed by the superior length of the Habsburg lances that allowed Habsburg soldiers to stab and maim the Swiss effectively from a distance.

- Silver Shields: Alexander's Crack Troops Who Betrayed Their New Master

- A Brief Overview of the Mamluks, the Elite Slave-Soldiers of the Islamic World

After a while the Swiss miraculously broke the deadlock, charging through the Habsburg lines and forcing Duke Leopold III and his contingents to charge forward at their enemy. In the pandemonium, the Duke and his men were killed and soundly defeated by the resilient Swiss, who breathed a heavy sigh of relief.

The Battle of Sempach had been an extremely close call, as the inferior length of the halberds had put the Swiss forces at a serious disadvantage in the earlier stages of battle. However, the Swiss did not learn their lesson that day, and continued to employ halberds as their primary armament in future engagements, a tactic that would eventually lead to the greatest military disaster in their history.

Nearly 40 years later in 1422, the Swiss were once again locked in the throes of combat, this time at Arbedo against the Milanese. The Italians had brutally re-captured the city of Bellinoza, one of the many cities that surrendered to the Swiss Confederacy following an expansionist drive starting at the turn of the century.

The Swiss swarms and their star halberdiers had been rampaging through Europe ever since the death of the Milanese warlord Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1403, capturing considerable amounts of territory south of the Alps in the valleys of Ossola, Maggia, and Versasca.

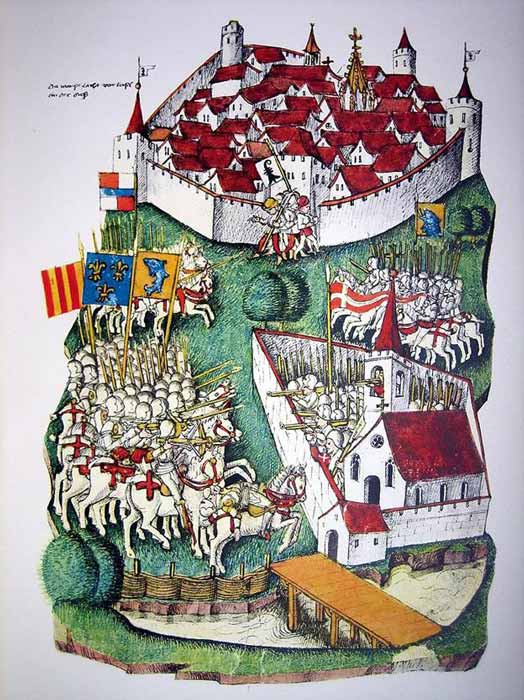

In the Battle of Arbedo 1422, painted by Benedicht Tschachtlan, the Swiss pikemen were too few and the other side with countless long pikes easily won. In the foreground the Swiss army, with the Milanese forces in the background. (Benedicht Tschachtlan / Public domain)

The two forces met at Arbedo, north of the contested city of Bellinoza, and the Swiss immediately found themselves outnumbered by the combined Milanese regiments. The Swiss sent 4,000 men to defend Bellinoza, whereas the Milanese dispatched 8,000 soldiers, twice as many as the Swiss. The Italians made the first move, and under the leadership of their commander Carmagnola they charged the square formations of the Swiss, who successfully repelled the aggressors with the stabs and thrusts of their halberdiers, killing 400 of the Italian knights. Unable to penetrate the immovable mass of the Swiss battalions, Carmagnola changed plan, ordering his knights to dismount to engage the antagonists, and his crossbowmen to launch volleys of projectiles into the Swiss flanks.

It was then that the Swiss resolve crumbled as the Italian lances, almost double the length of the halberds, slashed and cut the Swiss forces to pieces in mirror image of their floundering moment at Sempach.

It seemed that the only weapon that could touch the advancing Milanese were the pikes, but pikemen only consisted of less than a third of the Swiss force, with the shorter halberd being the more common weapon. The Swiss were only saved from total destruction when the Milanese mistook a band of passing foragers for Swiss reinforcements, motivating Carmagnola to order the withdrawal of his companies from the corpse-strewn battlefield.

Following Arbedo, the shellshocked Swiss, who hadn’t lost a major battle for decades, convened a meeting, called the Diet of Lausanne, to try to understand the reasons for their humiliation. Realizing that the shortness of the halberds had ultimately led to their demise, they expanded the use of the pike, making it the dominant weapon of their ranks.

By 1442, the pike was the primary weapon for a quarter of all Swiss soldiers, by 1500 it rose to half of all combatants, and by 1515 it was the favored weapon of two-thirds of the Swiss fighters. Swiss warriors were initially reluctant to adopt the pike, as it restricted their mobility, and its wieldy nature made it more difficult to plunder and pillage. In 1512, the Swiss were forced to ask the Milanese, now their allies, to provide pikes to their warriors who had brought with them too many halberds.

Despite the initial reticence, the hardy pike would catapult the Swiss to international fame, as their military might would become an unstoppable force and the talk of the European courts.

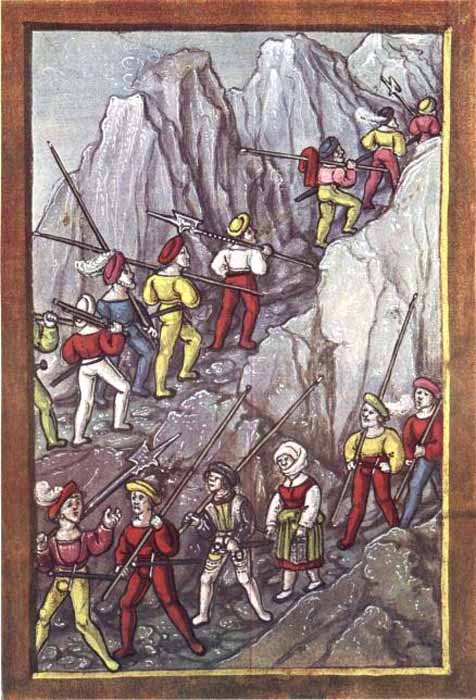

The Swiss pikemen were so famous and successful in battle that they soon became elite Swiss mercenaries for hire. Swiss mercenaries crossing the Alps by painter Diebold Schilling the Younger. (Diebold Schilling the Younger / Public domain)

Swiss Pikemen Success Leads to Lucrative Mercenary Jobs

Following the adoption of the pike as their main weapon, the Swiss pikemen enjoyed decades of military superiority in Europe and were responsible for some of the most crushing victories in the medieval era. Some of the most famous include the battles at Granson and Morat in 1476 and Nancy in 1477, where they annihilated the Burgundian armies, dispatching their eminent leader, Charles the Bold in the process.

Garnering attention from other notable European lords, they started to offer their services as mercenaries, becoming indispensable units in some of the most famous military outfits of the day. In 1424, Florence requested 10,000 Swiss pikemen, offering an enormous 8,000 Rhenish gilders for a mere 3 months of service, and in 1494, 6,000 Swiss mercenaries would join Charles IV as he invaded Italy.

Individually, the Swiss pikemen were weak, as the length of their weapons made it hard for them to defend against the slashes of swords, which could easily parry their attacks. However, when bandied together, the Swiss pikemen were a terrifying and unyielding conglomeration of sharp points which would advance on the enemy, often at speed, demolishing anything in its path.

The first 4 ranks would use their weapons offensively, jabbing at anything in range, while the men at the back, responsible for producing momentum, would turn their pikes upright and push their comrades in front of them. With the pikemen drawing their weapons at the side to protect their rear, the pike square assumed the appearance of a hedgehog, often forcing cavalry to dismount from their horses who would face almost certain death if they were to charge the dense wall of prickles.

The Swiss employed the pike square successfully on numerous occasions including at Granson and Morat in 1476 and the Battle of Novarra in 1513 against French forces. During the Battle of Schwaderloh in 1499, one of the Swiss’ most convincing victories, their German opponents would even try to imitate the Swiss tactics, failing miserably due to their inferior quality:

“…dismounted from their horses and came to the first rank with a good pike, and defended themselves so fiercely that it would not have been possible to defeat this smaller formation, if all had done like them. Then the confederates shouted ‘let’s go, let’s go, the bad guys are fleeing… They pushed with clenched fists so hard that the above-mentioned knights and the first three ranks were killed, but not without sweat and blood. The rear ranks took to flight.”

At the Battle of St Jacob in 1444, in a painting by Benedicht Tschachtlan, 1,500 Swiss soldiers perished against a French army that was almost twenty times bigger after repelling numerous French cavalry charges and killing 3,000 of Louis XII’s men. (Benedicht Tschachtlan / Public domain)

The Swiss pikemen were most effective in open and flat terrain, depending on an unobstructed thrust forward to secure victory. In 1494, Francesco Guicciardini would note the advantages of such favorable conditions for the Swiss hordes:

“They would face the enemy like a wall without ever breaking ranks, stable and almost invincible, when they fought in a place wide enough to be able to extend their squadron.”

The Swiss’ superior tactics were enhanced by the stunning bravery of their men, who would often fight until the last man. No Swiss force ever retreated from battle, even in rare defeat. At the Battle of St Jacob in 1444, 1,500 Swiss soldiers perished against a French army that was almost twenty times bigger after repelling numerous French cavalry charges and killing 3,000 of Louis XII’s men. The French monarch was so disheartened that he abandoned his conquests of Switzerland, switching his focus to the Habsburg Empire at Alsace, an easier opponent.

- Soldiers for Sale: Mercenaries from Ancient Times to Medieval Times

- Gallowglass Mercenaries – The Notorious Norse-Gael Soldiers of Fortune

The Swiss foiled yet another attempt at conquest in 1499, this time by the Habsburg emperor Maximillian I, whose 30,000 strong army was mostly wiped out. The propensity of the Swiss to defend themselves contributed to their perpetual independence throughout the 15th century, as their extraordinary martial abilities were never matched.

The resilience of the Swiss was strengthened by their powerful bonds of kinship, with Swiss pikemen usually fighting alongside their brethren, encouraging a spirit of self-sacrifice unparalleled in any other army in Europe. Fighters recruited from the Swiss countryside were usually placed in units of men from the same locale, and in the cities the Swiss brigades were made up of men who were members of the same guilds.

Contemporary lords realized this, and even tried to copy the Swiss model. 20 years before his crushing loss, Maximillian I, recognizing the power of blood ties, had insisting in 1479 that his Flemish infantry hires be from the same regions and towns.

In addition, Swiss mercenaries often refused to fight each other if they were on opposing sides. This was the case in 1494, when Italian warlord Ludovico il Moro was beaten after his Swiss mercenaries declined to fight against the French, who had also employed Swiss contingents. If their homeland was attacked, the Swiss would also withdraw to the chagrin of their employers. In 1524, 6,000 Swiss pikemen deserted Francis I four days before the Battle of Pavis, which the French would subsequently lose.

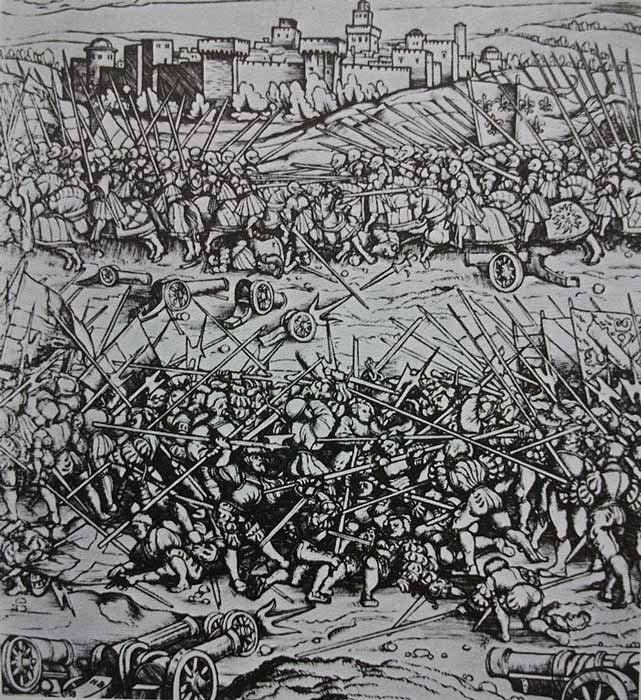

Before long the enemies of the Swiss pikemen developed tactics and weapons that made them easier and easier to defeat. In the Battle of Ravenna in 1512 AD, drawn here by an unknown artist, the Swiss were completely defeated! (Public domain)

Countermeasures and Downfall

Despite being seemingly near invincible, Swiss hegemony would end as effective tactics, in combination with the technological advancements of ranged weapons, were gradually developed against them.

Commanders noted that the Swiss were incredibly vulnerable on their flanks, which were often exposed. Despite the use of cascading pike squares as a countermeasure to this weakness, enemy warlords were soon able to evolve effective schemes that would focus on destroying the Swiss from the rear. They took advantage of the slow time it took the pike squares to change direction by rushing men in to initiate close combat on their unprotected sides. The size of the pikes meant they were powerless against close-quarter attacks.

Another effective stratagem was to force a breach at the front of the square, allowing enemy soldiers to rush into the center of the formation and cut down the men from the inside using daggers, axes, swords, and other short-handed weapons. At Ravenna, in 1512, the Spanish pulled this off successfully, puncturing a hole in the middle of the Swiss mass by sending soldiers to crawl underneath the pikes and cut them down with swords.

The best countermeasure, however, was ranged weapons. The large huddle of Swiss mercenaries made them an easy target for gunpowder-loaded artillery, which were developing towards the end of the Middle Ages. Marksman and cannoneers, located far away in relative safety and protection, could unleash their rounds without being overrun by the distant Swiss squadrons. This was used to great effect by the Spanish at the Battle of Biccoca in 1522, where the Spanish slaughtered 3,000 out of the 8,000 Swiss combatants with the help of ranged fire. The Swiss detested the artillerymen, who they saw as cowardly, as a lyric from a song about the Battle of Biccoca, composed by Niklaus Manuel, related:

“…in the ground as a pig in manure: they did not even have the heart of a man if they were not in an advantageous position.”

The Battle of Marignano in 1515 remains the textbook example of how to defeat the Swiss pikemen. Against one of the grandest Swiss armies of the century, Francis I employed every known counter-tactic to best the enemy. First he ensured that the battle was fought on a hilly plain, which would not only diminish the effectiveness of the strong Swiss thrust, which required flatter terrain, but also provide ample cover for his cannons and muskets.

The Swiss made a beeline towards the French artillery but were warded off by a combination of artillery fire, cavalry charges at the flanks, and injuries resulting from the uneven terrain. The next day, the Swiss were finished off by yet another rapid cavalry charge to their rear and the arrival of a Venetian vanguard which prevented them from fully breaching the French armies. The Swiss retreated despondent and broken, having lost half of their entire force.

Opportunities Missed and Opportunities Taken

If the Swiss had been politically united during their period of supremacy, there is no doubt they could have been another great power competing for European mastery. Swiss divisions, however, always remained an obstacle, and a Swiss empire, conquering in the same fashion as Phillip II with his legendary Macedonian pikemen ages earlier, would never come to pass.

- The Sacred Band of Thebes: Elite Fighters… and Lovers!

- 47 Ronin: The Samurai Warriors that Sought to Avenge the Death of their Master

The Swiss missed their chance, and after the colossal defeats at Marignano in 1515 and Biccoca in 1522 their feared pikemen would never again reach the dizzying heights of success they had achieved earlier during the 15th century. However, despite these devastating setbacks, the Swiss continued to be employed as skilled mercenaries, and were a vital part of the French armies until well into the second half of the 16th century.

Throughout the 17th and until 19th centuries they continued to provide their services, eventually settling in Italy, swapping leather jerkins and lightly armored steel breastplates for the flamboyant and colorful attire of the Vatican Swiss Guard, who from 1859 remain the only Swiss mercenary group permitted under Swiss law.

Top image: The Swiss pikemen today in a Pike Square re-enactment during the 2009 Escalade in Geneva. Source: Rama / CC BY-SA 2.0 FR

By Jake Leigh-Howarth