Getting Buzzed: The History of Hallucinogenic Mad Honey

Everyone loves honey. A delicious, sweet treat, it can be used in recipes, cosmetics, or as a sugar substitute. However, not all honey is made the same. This is incredibly clear in Nepal and Turkey, where a type known as “Mad Honey” is sold for nearly $360 per kilogram, or $160 per pound on the Asian black market. Mad Honey is redder in color than ordinary honey and has a far more bitter flavor, but is mostly known for its hallucinogenic properties.

Made by Apis laboriosa, the Himalayan honey bee - and largest honey bee in the world - Mad Honey gets its hallucinogenic properties from grayanotoxins. Grayanotoxins are found in the flowers, leaves, and stems of rhododendron plants, the primary plant Himalayan giant honey bees get their nectar from to make honey. Because of its hallucinogenic properties, Mad Honey has a fascinating ancient history that stems back thousands of years.

King Mithridates VI of Pontus, depicted on this coin, defeated the Roman army using Mad Honey. (ArchaiOptix / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Mad Honey: An Early Bioweapon

One of the earliest records of the use and effects of Mad Honey come from the book Anabasis by Xenophon. Xenophon, a Greek military leader and philosopher from Athens, was the commander of one of the largest Greek mercenary armies of the Achaemenid Empire in 401 BC. This army, called the Ten Thousand, was commanded to march on Babylon, but ultimately failed to capture it. Xenophon recorded this march in his book Anabasis, which describes a peculiar situation after the consumption of some wild honeycomb in the Turkish town of Trabzon.

In the account, Xenophon claims that there were plenteous beehives in the region, and that his men ate many honeycombs the evening they passed through the town. Soon after consumption, the men were reportedly violently sick with vomiting and diarrhea, and had “lost their senses,” unable to stand or even walk upright. The men lay in a heap that evening fully exhausted from the illness. The next day, the men had regained their faculties and were no longer sick, with not even a single soldier reported to have died. The march soon continued, but it is unknown if the army ever discovered why the honeycomb made them so ill.

Centuries later, Roman soldiers also discovered Mad Honey in 67 BC, a discovery that would soon turn disastrous. The soldiers were pursuing King Mithridates VI, the ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus, to kill him and capture his kingdom. With his Persian army, Mithridates developed a plan to defeat the Roman army using Mad Honey.

- Drugs in Ancient Cultures: A History of Drug Use and Effects

- Mithridates VI of Pontus: The Poison King of Pontus and Aggravation to Rome

Mithridates commanded his soldiers to fill the streets with pots full of Mad Honey for the Romans to find. Once the Romans found them, they naively consumed the honey, soon becoming incredibly sick just as the soldiers in the Ten Thousand had. Once the army was debilitated with illness, the Persians attacked, killing over 1,000 Roman troops with ease. It is one of the earliest examples of the use of bioweapons in warfare.

Empress Olga of Kiev performed similar deeds with Mad Honey. In 946 AD, she tricked Russian troops into drinking mead made from Mad Honey, which debilitated them enough that she and her followers killed over 5,000 delirious men. In 1489, Ivan the Great’s troops did the same, leaving behind giant containers of mead made with Mad Honey for the Tatar troops to drink and become ill. Ivan’s troops returned to the camp and slaughtered many of the delirious Tatar troops.

Though it is mostly found and used around the Black Sea, some Mad Honey has been found in the United States, though this is rare. Some rhododendron plants can be found amongst the Appalachian Mountains in East Tennessee, resulting in the local bees producing a milder form of Mad Honey. Tales from the Civil War share details about Union troops finding wild beehives in these mountains and eating the honey, experiencing the same symptoms as previously described. However, this is the only major incidence of this recorded in US history.

Apis laboriosa, the Himalayan honey bee, is known for making Mad Honey. (L. Shyamal / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Taking a Trip: How Mad Honey Works

As previously stated, Mad Honey is mostly made in Nepal and Turkey by the giant Himalayan honey bee. In some regions, the primary flower is the rhododendron, which gives bees little to no choice in the type of flower available to produce honey. These bees take their nectar from wild rhododendron flowers, which contain grayanotoxins in their petals and leaves.

When using the nectar to make honey, the honey becomes infused with these grayanotoxins, which cause the vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and other psychoactive effects seen in those that have consumed Mad Honey. The less floral biodiversity in the region, the stronger the Mad Honey is produced. Weaker versions of Mad Honey can be found in regions containing both rhododendrons and other flower species.

Scientists state that there are over 25 types of grayanotoxins that can be found in varying amounts in rhododendrons depending on the specific type of flower. These grayanotoxins cause their physical effects by binding to voltage-gated sodium ion channels in the body’s cells, which keeps them open longer. With these channels open, cells receive a higher influx of sodium and calcium, which leads to the release of acetylcholine.

Crazy honey" is reddish in color and of course - sweet, but it has psychotropic effects, and in small doses it is very pleasant. When taken in small doses it has amazing health benefits. #himalayancliffhoney #cliffhoney

#madhoney #redhoney #hallucinogenichoney pic.twitter.com/1758YsMHnW— Everest Organic Home (@OrganicEverest) January 8, 2021

This excess acetylcholine leads to the physical symptoms seen in those consuming Mad Honey such as vomiting, urinating, diarrhea, sweating, salivating, and emotional distress, a condition commonly referred to as cholinergic syndrome. Grayanotoxins are known to also cause a drop in blood pressure and heart rate in small doses, and can be fatal in high doses. Luckily, there are few reports of Mad Honey having high enough concentrations of grayanotoxins to be fatal to human beings unless taken in extremely high quantities.

Symptoms typically disappear within approximately 24 hours, though some symptoms fade before then. The more honey consumed, the longer it takes for it to be processed and expelled from the body. With knowledge of Mad Honey becoming more common, less poisoning cases are being reported annually, with Turkey now reporting an average of only 12 cases per year.

Though not typically fatal to humans unless ingested in high quantities, Mad Honey is much more likely to be fatal to animals such as dogs and cattle. As a result, there are significantly more reports of accidental Mad Honey poisoning in animals as they encounter the honey in the wild. Areas in which cattle are raised are frequently checked for both wild rhododendrons and Himalayan honey bees by ranchers to prevent cattle poisoning and death.

Himalayan mountains during the blossoming of rhododendrons, the primary flower needed for producing Mad Honey. (ggaallaa / Adobe Stock)

Recreational Drug or Future Medical Treatment?

Today, Mad Honey can still be found throughout Turkey and Nepal both publicly and on the black market. Though cheaper on the black market, safer, regulated versions can be found for a higher expense at public markets. With Mad Honey typically being found at higher altitudes such as in mountains and cliffsides, honey hunting can be a significant challenge. Harvesters of the honey frequently risk their lives traveling in unsafe locations to find natural beehives to take, process, and sell Mad Honey for a profit.

Some public sellers now keep the bees and rhododendrons themselves to make the process much safer for harvesters. To produce stronger Mad Honey, keepers must restrict the bees to an area containing only rhododendrons, so they do not have the chance to “weaken” the honey with the nectar of other flowers.

Mad Honey from Nepal is to die for. (Literally)#Psychedelic #RedHoney #MadHoney #Hallucinogen #Drugs #Nepal #HoneyHunters #Hallucinogenic #GoodTrip #BadTrip #MustRead #HotTake #Rare #mountains #savethebees#Trending #News #TrendingNowhttps://t.co/KtVACaUGrH

— Hot Take Ricky (@ricky_take) January 9, 2020

For those who use Mad Honey today, it is advised that only a small amount is consumed at one time. In small enough doses, the honey can cause mild intoxication that can result in decreased stress, euphoria, light-headedness, and mild hallucinations. In Mad Honey’s origin countries, some groups prefer to consume the honey instead of intoxicating themselves with alcohol, marijuana, or other recreational drugs. Others incorporate the honey into alcohol to produce a stronger effect.

However, even those that use Mad Honey frequently warn against the ingestion of pure rhododendron. By going through the process of becoming honey, Mad Honey has a significantly lower amount of grayanotoxins than the pure rhododendron plant. Ingesting even a small bit of the plant itself can induce serious symptoms that can land you in the hospital, or worse, the morgue.

Not everyone taking Mad Honey consumes it for the high, however. Some consume Mad Honey for the supposed lasting effects on the body, which they claim is more effective than pharmaceutical medications. Those that consume Mad Honey for the medicinal effects claim that it can relieve the pain of arthritis throughout the body, while others claim that it enhances sexual performance and treats erectile dysfunction. The latter belief has likely contributed to the rise in Mad Honey poisoning cases in middle-aged men in recent years.

Though there is not much to back up these claims, some research does suggest that minimal doses of grayanotoxins can produce beneficial effects in the body. Some of these effects could treat conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol, sore throats, and diabetes. In topical trials, balms made with grayanotoxins were shown to improve the healing of cold sores. Don’t go running for some Mad Honey just yet, however: these trials are still in progress, and results are not yet certain. Researchers hope to keep studying the effects of both grayanotoxins and Mad Honey in the coming years to determine if they could be used in future medicinal treatments.

- Honey Liquid Gold Of The Ancient World

- Wari Culture Used Alcohol and Drugs to Maintain Political Control

As of now, the honey can still primarily be found in Turkey and Nepal, though it can be legally imported in several US states outside of Indiana, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin as an herbal supplement. However, it is recommended that this substance not be used for medicinal purposes without the recommendation of a physician due to its unpredictable nature. What may start as a simple attempt to reduce anxiety can quickly turn into an evening of vomiting if taken in too large a quantity.

Though the research is not yet complete, the current findings about Mad Honey’s effects are fascinating. If research continues, it is possible that future discoveries could result in Mad Honey being incorporated as a natural remedy for some medical conditions. For now, though, we’ll have to wonder from afar about the potential of this distinct red honey.

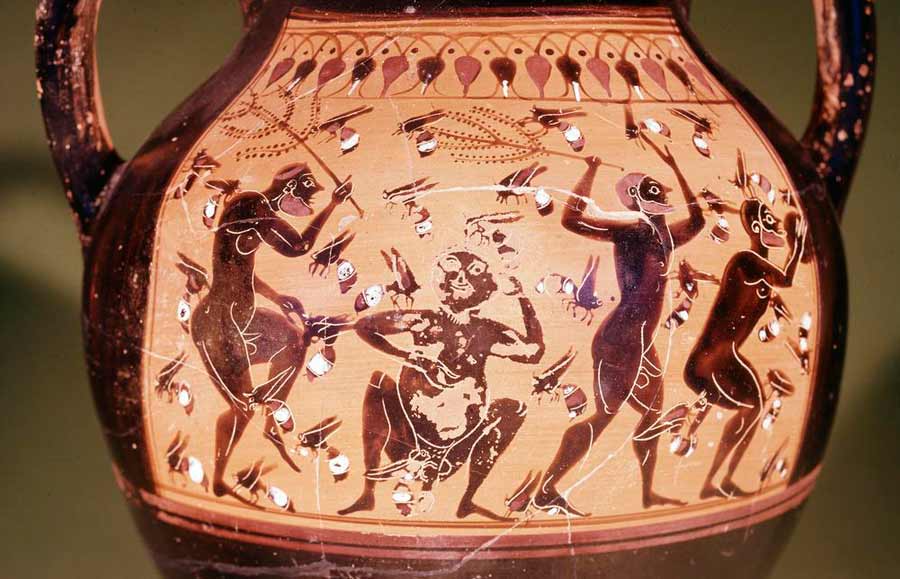

Top image: Amphora dating to circa 540 BC made in Attica, Greece, depicting bees from ancient Greek mythology. Source: The British Museum / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

By Lex Leigh

References

Bryce, E. 27 September 2019. “The strange history of 'mad honey'” in Modern Farmer. Available at: https://modernfarmer.com/2014/09/strange-history-hallucinogenic-mad-honey/

Henton, L. 21 May 2019. “Expert gives the buzz on mad honey” in Texas A&M Today. Available at: https://today.tamu.edu/2014/10/15/expert-gives-the-buzz-on-mad-honey/

Hess, P. 17 July 2017. “Mad honey: What to know before eating hallucinogenic honey from Nepal” in Inverse. Available at: https://www.inverse.com/mind-body/33974-mad-honey-nepal-rhododendron-grayanotoxin-hallucinogenic

Jansen, S. A. et. al. 19 April 2012. “Grayanotoxin poisoning: 'mad honey disease' and beyond” in Cardiovascular toxicology. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3404272/

Johnson, S. 23 April 2021. “'Mad honey': The rare hallucinogen from the mountains of Nepal” in Big Think. Available at: https://bigthink.com/health/mad-honey/

Ostrom, C. M. 17 July 2011. “3 new cases of foodborne illness identified in King County” in The Seattle Times. Available at: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/3-new-cases-of-foodborne-illness-identified-in-king-county/

Ullah, S. et. al. 22 May 2018. “Mad honey: Uses, intoxicating/poisoning effects, diagnosis, and treatment” in RSC Advances. Available at: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2018/ra/c8ra01924j