Chinese Knife Money: Making Markets feel Murderous?

The days of ‘cash as king’ are fading. Today, credit, debit, and digital currency have begun to slowly replace cash as the primary forms of payment, but it was not always so. For centuries, paper money and metal coins were traded around the world. But did you know there are forms of currency that predate even these familiar forms of money?

The Evolution of Currency during the Zhou Dynasty

Humans have used metal coinage for thousands of years, but before this (at least in China) currency was made to resemble common commodities of the time. The Zhou Dynasty in China lasted from 1100 BC to 256 BC. However, from 700 BC onwards, the Zhou state was declining, leaving matters of currency to be decided primarily by local governments.

The origins of these forms of money are still being debated by numismatists, or specialists in currency and coins. There are some who believe that knife money originated when a Chinese prince ran out of funds to pay his soldiers. He then allowed them to trade their weapons instead. Another version of the story claims that the prince issued fines to his people in such massive amounts that they couldn’t hope to pay. In turn, he decided he would accept knives as payment. These stories, however, appear to be just that. There is no scholarly consensus on the origin of knife money.

The state of Chu was the first to use a common item as currency, in the form of cowrie shells. When there weren’t enough shells to go around, imitations were created out of bone, stone, and even bronze. Spade money, known as jin, was common in Shanxi and Henan provinces. These fragile, hollow-bodied coins date back as far as 1200 BC, and they were the earliest examples of currency imitating tools.

Knife money, or dao bi, emerged around 700 BC (although this is still debated) in the provinces of Qi, Yan, and Zhao. Some early forms of the currency were designed so that they could still be used as knives, although the edges were rarely sharpened. Additionally, there were various styles of knife money. The design changed depending on where and when the coins were minted.

- Paying With Shells: Cowrie Shell Money Is One of the Oldest Currencies Still Collected Today

- When – and Why – Did People First Start Using Money?

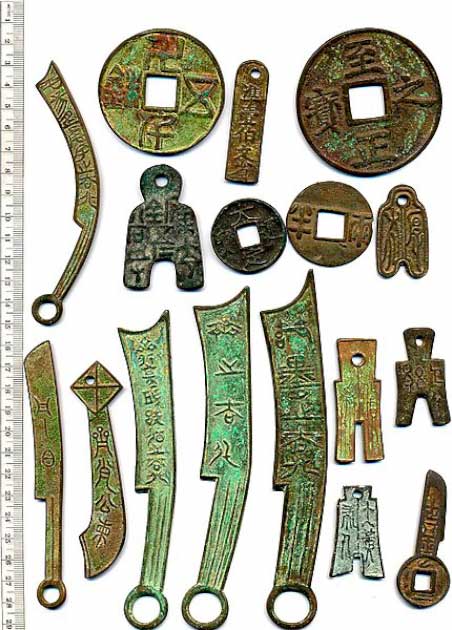

Collection of Chinese numismatic charms and amulets (Scott Semans / CC BY 3.0)

The Many Forms of Dao Bi Knife Money

The general shape of knife money traces back to the xue, a scraper blade with a ring at the end of the handle. A common feature between the many forms of dao bi is the ring that they, too, have at the end of their handles, which early numismatist W.B. Dickinson suggested was used to thread the money onto one’s belt. Here, however, the common features end.

Modern numismatists believe that the pointed knife was the earliest example of knife money. These bear a resemblance in workmanship to some forms of spade money, and so are believed to have emerged around the same time.

Ming knives were the most common form of knife money. Each is inscribed with the character, “Ming” on one side. There are several variations of Ming knives, differentiated by the curvature of their blades. Some have a more angular blade, while others are slightly curved. The latter are believed to have evolved from pointed knives.

Straight knives are, as the name suggests, straight bladed. These were the first to bear inscriptions that are believed to correspond to specific mints. Heavy knives are sometimes referred to as the earliest form of knife money, but this is debated among scholars.

- Fragments of Chinese Coins Are Evidence of World’s Oldest Minting Site

- Rare Ming Dynasty Banknote Found Hidden Inside a Chinese Sculpture

Ancient Chinese bronze Qi knife coin (Public Domain)

Qi Knives: The Rarest Form of Knife Money

There are several categories of Qi knives, determined by the number of Chinese characters inscribed down one side of the blade. Three-, four-, five-, and six-character knives have been discovered, but all of them are quite rare.

Six-character knives are the rarest, and numismatists believe they were minted as a commemorative coin to mark Tian He’s rise to power in 386 BC. His ascent ended the six-century long rule of the state of Qi by the House of Jiang.

There is a great deal of mystery and disagreement regarding knife money. Archaeological digs continue to uncover specimens, but their relative rarity means that there is still a great deal left to learn. In the 4th century BC, several states in China began minting round coins with holes in them. When Qin Shi Huangdi became China’s first emperor, he issued a standard currency known as Ban Liang, which were round coins with a square hole. Cowrie, spade, and knife currency were discontinued and were cast into the soil, to be unearthed centuries later.

Top image: Chinese knife money. Source: sytilin / Adobe Stock

By Mark Johnston

References

Andrei, M. March 28, 2011. You Should Know about Chinese Knife Money. Available at: https://www.zmescience.com/other/chinese-money-28032011/.

Anonymous. October 2021. Casting was Thriving and Systemized 2800 Years Ago. Modern Casting.

Ashkenazy, G. December 9, 2014. State of Qi Six Character Knife Money. Available at: https://primaltrek.com/blog/2014/12/09/state-of-qi-six-character-knife-money/.

Bergeron, D. Autumn, 2011. Early Chinese Coinage. Bank of Canada Review.

Calgary Coin and Antique Gallery. N.D. Chinese Cast Coins. Available at: https://www.calgarycoin.com/reference/china/china1.htm.

Dickinson, W.B. 1862. On Chinese Knife Money. Available at: https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.mtroyal.ca/stable/42680078?sid=primo&seq=7#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Comments

That’s quite a theory.

Maybe... just sinful, greedy, lust for power brought us that trick, whereby the trickster could gain power by accumulating some arbitrary (fake) measure of value, in most cases via slicing up non-ferrous metal rods (rods being the product of the smelting operation) and making it a game to accumulate the slices, which later were always stamped with the head of trickster. Of course it was a net-zero shell game, paid for by those who were, and still are, tricked by it.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.