The Battleground Origins of Jujutsu

It’s likely that if you’ve ever seen a Hollywood action film you’ve probably heard of jujutsu. Thanks to films like The Matrix and the John Wick franchise, jujutsu is more in the public eye than ever before. But what most people don’t know is that jujutsu’s origins go back to the 8th century Japanese warrior class. Jujutsu, once a weapon of war, has evolved over the centuries into something quite different. Still a popular martial art in its own right today, it has gone on to form the basis of many more modern fighting styles. It has a long and rich history worth studying.

What is Jujutsu?

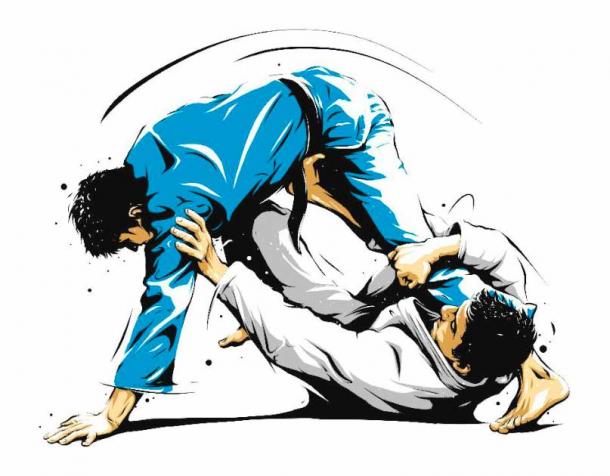

Jujutsu is a family of Japanese martial arts that specializes in short-ranged, predominantly unarmed combat. It can be used either defensively or offensively and is characterized by a use of throws, holds, and attacks meant to paralyze the opponent.

Jiu-jitsu fighters sparring. (quicklinestudio /Adobe Stock)

The word jujutsu can be broken down into two parts. “Ju” can be translated as gentle, soft, supple, pliable, or yielding. Jutsu can be simply translated as an art/ technique. When we combine these translations it gives us “yielding art”.

- Egypt’s Ancient Tahtib Martial Arts Form: Stick Fighting Warriors!

- The Origins of the Top 5 Most Ancient Martial Arts that are Still Practiced Today

Yielding art leads us straight to jujutsu’s guiding philosophy. The goal of jujutsu is to use an opponent’s force against themself rather than using one's own brute force. Whilst different jujutsu schools teach different variations of the original art form to fit different niches, they all still follow this centuries-old philosophy. But where does this philosophy come from?

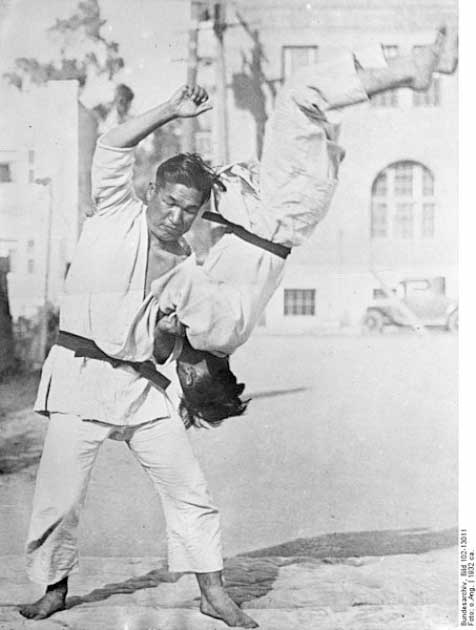

Men practicing jujutsu in 1932. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-13011 / CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Origins of Jujutsu as a Weapon of War

The word jujutsu was first coined in the late 8th century during the Nara Period (710-794 AD). The original form of jujutsu, now known as Japanese old-style, combined early forms of sumo and other early Japanese martial arts and brought them under one umbrella.

Jujutsu developed as a countermeasure against the samurai of feudal Japan. The samurai were well-armored which made striking ineffective. Jujutsu practitioners were taught the most efficient ways of taking down an armored and armed opponent in close quarters. This was done by using pins, joint locks, and throws. Practitioners were taught to use the samurai’s energy against him.

Unsurprisingly fighting an opponent wielding a razor-sharp samurai sword completely unarmed was a hard sell. In response to this, the oldest known jujutsu styles - Shinden Fudo-ryu (1130), Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu (1447), and Takenouchi-ryu (1532) integrated small arms into the jujutsu teachings. Practitioners were taught how to parry and counterattack long weapons like spears and swords with a dagger or other small blade.

Jujutsu’s next major evolution came during the Edo period in the early 17th century. Influenced by the Chinese philosophy of Neo-Confucianism, the Tokugawa shogunate brought strict laws to reduce war. As jujutsu had been invented as a weapon of war it had to evolve rapidly if it was going to survive.

Samurai of the Shimazu clan. (Public Domain)

This peaceful new ideology meant that armor and weapons became little more than decorative items. This led to a rise in teaching hand-to-hand combat as a form of self-defense but was also bad news for jujutsu - a style specifically designed to counter armored opponents.

Jujutsu schools quickly began to incorporate striking moves, which were effective against unarmored opponents, into their teachings. The strikes were normally aimed at the weak spots on the body - the eyes, throat, and back of the neck.

The striking trend in old Jujutsu was short-lived. Towards the start of the 18th century, the majority of striking techniques were dropped as practitioners had decided the moves were largely ineffective and wasted too much energy. Whilst some striking techniques remained, their purpose was to leave an opponent unbalanced and open to follow-up grapples rather than damaging them outright.

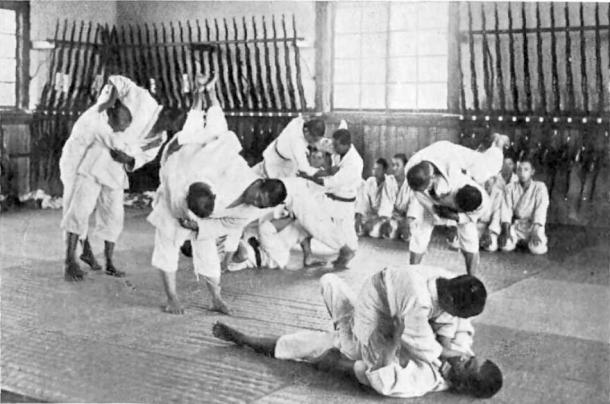

During this period warriors had little to do, and so recreational martial arts became increasingly common. Jujutsu schools would challenge each other to see whose styles were best. These competitions led to the rise of randori. Randori was a form of free-style practice/ sparring which ensured the shogunate's strict new laws weren’t broken when the schools challenged each other.

Jujutsu training at an agricultural school in Japan around 1920. (Public Domain)

Later Development of Jujutsu

As time progressed Jujutsu continued to evolve and diversify into different schools. Different forms of jujutsu were taught to combat specific threats or to meet specific use cases.

Edo jujutsu became popular during the Edo period (1603-1867). This form of jujutsu specialized in dealing with unarmored opponents in a more urban environment rather than the battlefield. Whilst largely unarmed it also taught the basics of using a small blade to defend oneself.

During this period Sengoku and Edo jujutsu also introduced a series of techniques known as Hojo waza. Hojo waza uses a Hojo cord to restrain and/ or strangle the opponent. Whilst the Hojo cord lost popularity over time it is not completely forgotten. Today Tokyo police officers still carry a hojo cord to restrain criminals alongside their more modern handcuffs.

As jujutsu evolved, a classification was needed to divide between the old and more modern schools. Generally speaking, any tradition predating roughly 1868 can be identified as koryu (ancient traditions) whilst anything which came after this time is known as Gendai Jujutsu or modern jujutsu.

Gendai traditions were founded after or towards the end of the Tokugawa period (1868). Modern jujutsu carried on moving further and further away from the original koryu teachings, dropping the use of traditional weapons and moving away from the use of standing arm locks and joint-locking throws.

This does not mean that jujutsu stopped being used as a weapon of war. The opposite is true. Since the early 1900s, every country's military has taught an unarmed combat course which is at least partly founded on the teachings of jujutsu. It is also not uncommon for modern police forces to incorporate jujutsu teachings into their training.

- Feisty Grandma Keeps Ancient Indian Martial Art Alive

- Pankration: A Deadly Martial Art Form from Ancient Greece

Jujutsu Continues to Evolve

Jujutsu has continued to evolve well into the 20th and 21st centuries. It is more than likely it will continue to do so. Apart from its use in military teaching, jujutsu's biggest evolution over the last couple of centuries has been as a martial arts sport.

This move to a sport-based martial art has seen the introduction of many new modern schools such as Aikido, Judo, Sambo, and Brazilian jujutsu. These all take certain elements of more traditional jujutsu and further evolve them into something new.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu fighters. (Miljan Živković /Adobe Stock)

Today there are hundreds of different schools of jujutsu all forming new branches of one ancient art. As jujutsu continues to grow and becomes increasingly popular in modern pop culture it is important to remember and pay respect to the traditions it sprouted from.

Top Image: Jujutsu practitioner tightening their belt. Source: Soloviova Liudmyla / Adobe Stock

By Robbie Mitchell

References

Bowman. P. 2020. The Invention of Martial Arts. Oxford University Press

Hashashin. B. 2015. History of Jujutsu. Medium.com. Available at: https://medium.com/@harrysuke/history-of-jujutsu-a2906aeb677a

Serge. M. 2001. Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryu Jujutsu. Kodansha International. Available at: https://archive.org/details/classicalfightin00mols