Roman Centurions: Elite Forces of the Roman Empire’s Military

The ancient world had some impressive military forces. For example, Egypt was famed for its chariots and Greece for its navy. The Romans? They were famous for their foot troops, the legionaries. Yet an army is only as good as its leaders. In the case of the Roman army, these were the centurions, Rome’s most elite troops. Centurions were military officers famed for their experience and valor in battle. When a situation got rough, the common legionary turned to their centurion.

Who or What Was a Centurion?

As we will see, the role of the centurion evolved with the Roman army. Generally speaking, a centurion was an officer in the Roman army. Each centurion commanded a unit of legionaries numbering roughly one hundred (hence the name). As an officer, the centurion would assign his men duties, hand out punishments, and carry out various administrative duties.

The life of a centurion was not solely spent on the front line, however. After serving his time, a successful centurion could leave the bloodshed behind and become a high-level administrator of the empire. Being a pen-pusher was less glamorous than leading the charge in battle, but it was more lucrative and much safer.

- The Roman Legions: The Organized Military Force Of The Roman Empire

- Roman Weapons: Sharp Blades to Conquer the Ancient World

Historical reenactor in centurion costume, from LEGIO SECVNDA AVGVSTA. (Hans Splinter / CC BY ND 2.0)

Who Were the First Centurions?

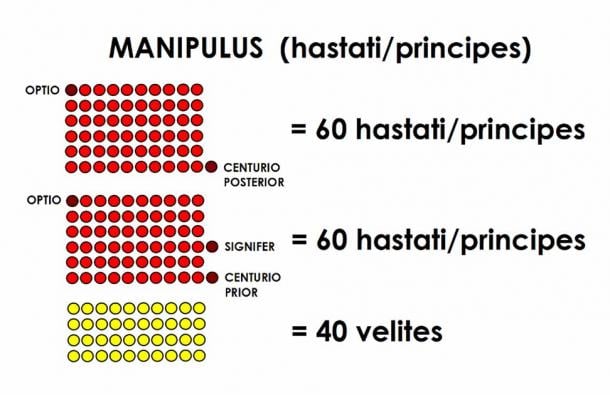

In Roman tradition, the rank of centurion went back to Rome’s first army. The Roman army of the mid-8th century BC was led by Rome’s namesake, Romulus. He was said to have had 3,000 men under his command, led by thirty centurions. A quick bit of math tells us that each centurion led his own group of one hundred men. These infantry groups of one hundred men were called a manipulus. Each manipulus had its own standard (a signa).

The organization of the Roman military, and the forces under centurion control, changed over the centuries. Greek historian Polybius described the manipulus formations of the 3rd – 2nd century BC Punic Wars in his text The Histories (Cristiano64 / CC BY SA 4.0)

Dionysus of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian from the 1st century BC, told a different tale. According to him, the centurion rank was of Etruscan origin. The rank was incorporated into the Roman army during the 5th century BC by the Etruscan king of Rome, Servius Tellius. The rank was granted to the army's bravest and most courageous men.

In reality, it is likely the role of the centurion was incorporated into the armed forces to help control Rome’s growing and constantly evolving army. By the end of the 6th century BC, the army was made up of two legions. Each legion was made up of around 4,500 men: 3,000 heavy hoplite infantry, 1,200 light infantry, and 300 cavalrymen.

The 4th century BC saw a further shake-up of the army. The manipuli were changed to be more flexible. They were now deployed in three lines of troops (called acies triplex). Each centurion then only commanded a group of thirty infantry, allowing more micro-management.

The organization of the army had changed once again by the end of the 2nd century BC. Each legion then had 4,000 men. Legions were divided into thirty manipuli. Each manipuli had sixty centuriae units that answered to their centurion commander. To help him, this centurion was allowed to appoint his own junior officer (called an optio). Centurions were expected to take a position in the first rank of their troops during a battle and lead by example. This inevitably meant the centurions had a disproportionately high fatality rate.

If a centurion managed to live long enough, he could rise to the rank of primus pilus. The primus pilus was the most senior of all the centurions and was allowed a seat on the empire’s military council.

By the 1st century BC, the Roman army had gone through yet another restructuring. The army was split into different cohors (cohorts). Each cohort had six centuriae, which were in turn made up of one hundred troops and one centurion. Each legion had ten of these cohorts, bringing the number of centurions in each legion up to sixty.

A centurion's seniority depended on the type of troops he commanded and the seniority of his centuriae within his respective cohort. Hastatli was the lowest, meaning the centurion’s troops were young and inexperienced. After this came the principes, which meant they were experienced and respected troops. Finally came the pili, which meant the troops under the centurion's command weren’t just experienced, they were battle-hardened veterans.

- Roman Siege Engines Tracked and Traced in Jerusalem

- Roman Decimation: The Cruelest Form of Punishment in History?

A centurion’s seniority determined the skill level of his assigned troops. Lower ranked centurions might end up with hundreds of inexperienced legionaries. Bas-relief carving of a Roman legionary out of battle dress, c. 1st century AD (Magnus Manske / CC BY SA 3.0)

Who Could Become a Centurion?

Perhaps surprisingly for such a respected role, the basic entry requirements to become a centurion were relatively low. Traditionally, most centurions were of the lower plebeian (common) class. By the 1st century BC, this had changed slightly, and the rank had become closely associated with the higher-ranking equestrian class.

You did not have to be Latin to become a centurion. There were five ways a soldier could become a centurion. A centurion could be appointed by election or by the Roman senate. If a legionary had shown particular bravery or leadership skills in the heat of battle, he could also be promoted from the ranks.

Things became more political during the Imperial period, and it became possible to become a centurion through a direct commission, with no prior military experience. There were even some rare cases of the emperor himself directly appointing centurions.

As the army evolved, so did the role of the centurion, and this meant the requirements became stricter. For the higher ranks, centurions were expected to be competent in administration. As things became even more political, the support of an influential patron became increasingly important.

It wasn’t all bad though. Centurions were eventually able to rise to surprisingly high levels within the empire. They could become mid-level officials like tribune or prefect, or even members of the Roman Senate itself. The greatest centurion success story is probably that of Emperor Maximinus Thrax (235-238 AD). Originally a centurion under Caracella, he rose through the ranks to become emperor.

A bust of Emperor Maximinus Thrax (235-238 AD). Although he rose through the military ranks to centurion and finally emperor, he never stepped foot in Rome as emperor (José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY SA 4.0)

The Uniform and Armor of a Centurion

The helmet of the centurion is perhaps one of the most iconic pieces of military equipment of all time. The helmet was called a galea and had a transverse crest along the top. The crest was usually silver and decorated with a plume of either dyed hair or feathers (usually ostrich or peacock).

The galea saw some evolution over the centuries. During the Imperial period, the crest could be front to back rather than transverse. Early helmets sometimes came with a faceguard or, even better, a mask. These masks were designed to frighten the enemy and were sculpted to resemble demons and monsters, much like the Oni masks worn by Japanese samurai. In the later Roman Empire, the helmet was decorated with silver insignia.

Modern reconstruction of a centurion's helmet, first century. The embossed eyebrows and the circular brass bosses are typical of the Imperial Gallic helmets. (MatthiasKabel / CC BY SA 3.0)

Centurions were also better-armored than your average legionary. They wore decorated greaves (leg armor) called ocrae. To protect their torsos they commonly wore a bronze cuirass (breastplate) called a thorax studios. These cuirasses were either belly-shaped or sculpted to resemble rippling muscles.

Depending on the conditions they were fighting in, a centurion could choose to wear a lighter version of his cuirass called a linothorax. This was made of leather and offered more maneuverability. These armors for the torso also sometimes came with shoulder guards (humeralia).

The areas left unprotected, like the groin and arms, were protected by hanging leather strips ( pteryges). By the 1st century AD, advancements in armor design meant short-sleeved ringmail vests had become the armor of choice for most centurions.

Roman centurion armor (Thomas Quine / CC BY 2.0)

Under their armor, a centurion wore a tunic, which was usually some shade of white or various shades of red. They could also wear a cloak called a sagulum which was either blue or green and bordered in yellow. The cloak was tied at the front with a fibula.

Just in case the centurion didn’t stand out enough already, he carried a 90 centimeter (35 inch) stick cudgel called a vitis latina. The centurion could raise this stick into the air to ensure his men knew where their commander was. There were two shields on offer, the circular clipeus or the rectangular scutum. While the centurion could choose his own shield, it seems they typically carried the same shields as their troops.

A historical reenactor in typical Roman centurion dress and armor, including leg armor and cudgel (Medium69 / CC BY SA 3.0)

To top it all off, the centurion wore any awards they had received. These could be heavy necklaces called torques, bracelets called armillae, or medallions called phalerae. Unsurprisingly, with the way they stood out and led from the front, the centurions had a high mortality rate.

The Weapons of the Centurion

The weapons a centurion carried were largely a matter of choice. They typically carried a sword ( enis) and spear ( hasta). Unlike typical legionaries, a centurion wore his sword on his left side, not his right. A centurion could pick his own style of sword, but for much of the empire's existence, two styles were prevalent. These were the xiphos, a straight, double-edged sword, and the curved machaira.

Modern reconstruction of a xiphos (Phokion / CC BY SA 4.0)

Later on, centurions began to wield a sword with a little more bling, the gladius hispaniensis. This sword came in at around 65 centimeters (26 inches) long, and came with either a trilobate or hemispherical pommel. The sword was carried in a silver scabbard that hung on a strap either over the shoulder or across the chest. It was also not unusual for a centurion to carry a dagger called a pugio. This was a 25 centimeter (10 inch) blade that hung from the belt and could be used to finish off wounded enemies.

Image of Roman legionary historical reenactor with Gladius sword, taken at the 2007 display of Roman Army Tactics, UK (David Friel / CC BY 2.0)

What Did a Centurion Do?

The most basic duty of a centurion was to lead his men into battle. They were expected to lead by example by fighting bravely and refusing to surrender when the odds were against them. Any centurion who failed in this duty brought shame on his legion and faced the death penalty.

The upside of this was that most centurions commanded the respect of their troops. This was important, as centurions were responsible for training their legionaries, handing out duties, and dishing out reprimands. Having the respect of their men made all these duties that much easier.

Centurions were known as harsh taskmasters who weren’t afraid to dish out grueling punishments. They oversaw the building of camp fortifications, the digging of trenches, and roll calls. Centurions were responsible for the security of their camps, and it was down to them to issue the passwords which were used to enter the camp.

The centurions were seen as the best of the best, and this was often reflected in the military assignments they were given. They were selected for special missions, like raids into enemy territory and high-priority reconnaissance, making them akin to modern-day special forces.

As time went on, the centurion role shifted. By the 1st century AD, they were most commonly assigned to commanding the army's special police and intelligence units, called frumenttarii. They could also be assigned to command units made up of non-citizens, such as those from allied armies.

During the frumentarii’s early history, they were tasked with supplying grain to the military, delivering messages between the provinces and the empire, and collecting tax money. In later years, they became involved in special intelligence, spying, and assassinations. Detail from Trajan's Column, relief 81 (Public Domain)

The most experienced centurions (if they lived long enough) trained troops as exercitores or acted as aides to governors. The most senior centurions joined war councils, where they helped come up with battle strategies or took part in peace talks with rival armies.

The centurions peaked in the Imperial Period. They could join the emperor’s personal bodyguard, the Praetorian Guard, and after sixteen years of service were eligible to join the evocati. The evocati were urban administrators, which could be an incredibly lucrative role.

Centurion pay wasn’t too bad either. In the late Republic, they were paid on average five times more than the average legionary. They also got a greater share of war booty. For example, in 64 AD Pompey gave each centurion a 1000 drachmas bonus, whereas legionaries only got 50. By the 1st century AD, centurions were at least paid fifteen times more than the men below them.

This isn’t all to say that the centurions didn’t have a dark side. Although famed across the empire for their honor and bravery, centurions weren’t above receiving a bribe or two. It was common practice for a centurion to bolster his already ample salary with bribes. These bribes often came from their men, who would offer coin in exchange for cushy assignments or promotion recommendations.

Conclusion

In ancient Rome, the centurions were the best of the best. They represented everything their men were supposed to aspire to be: disciplined, loyal, and fearless in the face of the enemy. They led by example and leapt head-first into the fray. Despite their fancy armor, this meant they had a fatality rate much higher than that of their men. Being a centurion was no cakewalk.

Sadly, as time progressed and the empire began to rot from the inside out, the role of the honorable centurion began to change. It became increasingly political and profitable to become a centurion. To this day, centurions are often held up as one of the greatest military leaders of all time; in their prime, it was a reputation they more than deserved.

Top image: Roman centurions like this were the backbone of the Roman army. Source: Fernando Cortés / Adobe Stock

By Robbie Mitchell

References

Cartwright, M. July 4, 2014. Centurion. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Centurion/

Hornblower, S. 2012. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

Knighton, A. December 22, 2017. Roman Centurions: Commanders of Men- A High Chance of Death. WarHistoryOnline. Available at: https://www.warhistoryonline.com/ancient-history/roman-centurions.html?chrome=1