Bleeding Your Way to Health: The Horrible History of Bloodletting

Bloodletting, or phlebotomy, is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “the surgical removal of some of a patient’s blood for therapeutic purposes.” Throughout the majority of history, this gruesome, and often messy, practice was favored by physicians all over the world, from Fiji to Western Europe, intent on giving their patients the best possible treatment. However, as time unfolded, from ancient to modern periods, the distinction between patient and victim became increasingly blurred.

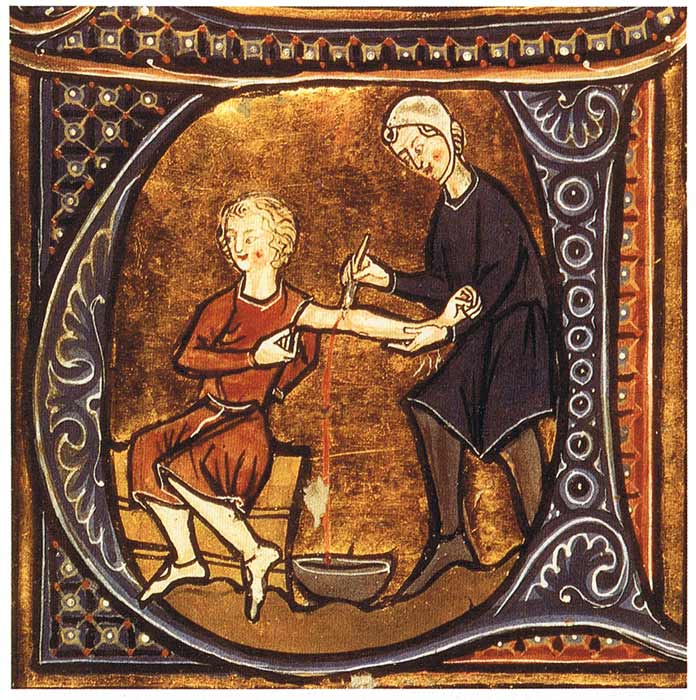

There were a variety of methods to draw blood. Venesection, the most common procedure, involved cutting the cubital vein at the elbow with tools such as a fleam, which possessed multiple sized blades, and a thumb lancet, which had sharp double-edged blades.

More primitive methods included scarification, which required the physician to cut and etch the skin to make permanent scars, and cupping, which removed the blood out from a small incision using a suction cup. Leeches were also commonly employed for their blood-sucking capabilities, as each one was able to engorge 5 to 10 milliliters of blood, around 10 times their own weight. However, as history reveals, these techniques were often more lethal than life-saving.

Bloodletting scene from 13th century Iran. (Anagoria / CC BY 3.0)

The Early History of Bloodletting

The Egyptians are believed to be the first people to have practiced bloodletting, as two references to scarification can be found in the Ebers Papyrus. By 500 BC, the procedure was well established in ancient Greece, as Hippocrates, the father of medicine, recommended bloodletting as a treatment, especially at the elbows and knees.

His successor, Herodotus, went on to recommend bloodletting for a variety of ailments in 400 BC that ranged from restoring appetite, curing disease, and improving sleep quality. In 100 BC, Celsus, the Roman medical author, like Herodotus, also expressed strong support for cupping, and recommended it alongside scarification to target local areas of the body.

It was in the 3rd century BC that Greek anatomist Eristratus, who treated Syrian kings, first hypothesized that illness arose from the the over-abundance of blood. This idea was later developed by Galen of Pergamum in the 2nd century AD, a disciple of Hippocrates, who subscribed to his master’s theory of the humor system, which contended that the human body was made of four humors: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm.

Galen proclaimed blood to be the most dominant humor, and as a result he became one of the first staunch advocates of bloodletting. Galen was of the opinion that cuts behind the ears could ameliorate headaches and vertigo and that a similar incision on the temple could help fix eye conditions.

- Human Blood Found on Ancient Maya Arrowheads, Bloodletting Rituals to Feed Life Force to the Gods

- In a World with No Antibiotics, How Did Doctors Treat Infections?

According to his contemporaries, Galen was known to get a little carried way with his bloodletting surgeries. “Man, you have slaughtered the fever,” one is reported to have said in reaction to the large and messy amount of blood taken from one patient. Thanks to Galen, bloodletting became a standard approach, not only in the Roman Empire which he was citizen of, but even further beyond into the medieval and modern eras.

During the first millennium AD, bloodletting would feature in a variety of religious texts produced at the time. In the Jewish Talmud, the central Rabbinic Jewish text written between 350 to 500 AD, bloodletting was a permitted treatment, so much so that the ancient text taught that a wise man should not live in a town without a bloodletter. However, not every Jewish scholar encouraged it, as Leviticus 19:28 forbade cutting into the skin.

Bloodletting was also instrumental in the medicinal armory of the ancient Middle East, being mentioned by the prophet Mohammed three times in the Quran, who declared that there were 3 ways to cure illness: “a drink of honey, a scratch of Hijamah, and cautery”.

Outside of Europe and the Middle East, bloodletting was also adopted by other ancient societies. The Baganda tribe in Uganda and the Aborigines of Australia, for example, regularly used it to relieve headaches. In Fiji, the sharpness of bamboo shoots mimicked blades to draw blood, and in ancient Sumatra there was a belief that “bad blood” had to be buried underground.

In addition, the native peoples of ancient Patagonia were said to bleed themselves to get rid of bad spirits, in Mesoamerica the Aztecs frequently pierced their body parts and offered their blood to the gods in order to achieve trance-like states, and in ancient India leeches and cupping were routinely applied to sick patients.

Late 13th century depiction of physician letting blood from a patient. (Public domain)

Medieval and Early Modern Bloodletting

Moving into the medieval age, bloodletting continued to be a dominant therapy employed by doctors and physicians. Medieval Arab practitioners developed several rules and superstitions, recommending that bloodletting should not be attempted on a full moon or when the wind blew south, and that blood should be taken at a safe distance from the infected area or on the opposite side of it.

In Europe, bloodletting became a standard remedy for plague, smallpox, epilepsy, and a host of other deadly maladies. However, following a papal decree in 1163 which prohibited priests from bloodletting, the practice was adopted by barbers, who in time became known as barber-surgeons. In fact, the red and white pole commonly seen at hairdressers came from the blood-stained towels that would dominate their workplace.

In medieval England, it was normal to have a “bleeding-house” or a “flebotomaria” in the wide array of abbeys that dotted the landscape. At several points of the year people were purposely bled to maintain good health. Members of the order of St. Victor, for example, had to be bled five times a year: before Advent, before Lent, after Easter, on May Day, and at Pentecost.

According to a manuscript entitled An Gude Boke of Medicines written in 1595, specific days of the year were marked as favorable, as a bloodletting procedure on April 3rd would ensure no headaches, on April 18th no fever, and on September or December 17th that: “he shall not fall in no dropsie, fransy or tisyke.”

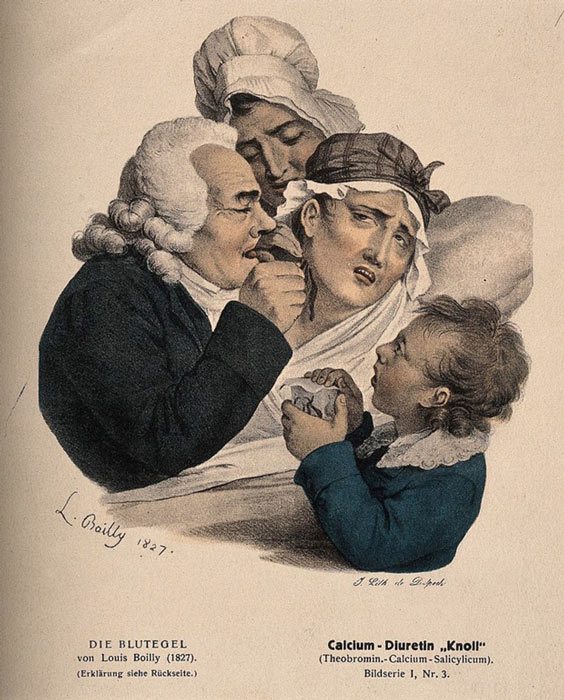

Later, into the 18th century, bloodletting continued to be prescribed by doctors, where its uses were expanded to treat fever, hypertension, headaches and inflammation. One doctor, John Hunter, believed that bleeding could be beneficial to smallpox and gonorrhea, with unfortunate patients suffering from the latter affliction having leeches applied to their scrotum to combat swelled testicles.

It was during this century that the application of leeches became more widespread. In the belief that all fevers were due to organ inflammation, French physician Dr. François Broussais promoted the use of leech treatment alongside bloodletting to target inflamed areas of the body. It was a practice which became very popular during the 1830s in France, where 35 million leeches were used every year in the country.

Bloodletting was always viewed as an important treatment in times of disaster. It was considered a key method to fight off the cholera epidemic of 1831, and during the American Civil War between 1861 and 1865, it was employed to tackle overwhelming cases of infection and disease.

Jacob Franszn (ca. 1635-1708) and family in his barber-surgeon shop. (Public domain)

Famous Cases of Bloodletting

Despite its massive popularity for millennia, there are several famously fatal cases of bloodletting. French conqueror Napoleon was one of the few to survive venesection, an experience he found so traumatic that he stated after that “medicine is the science of murderers.” Other prominent survivors included French queen Marie Antoinette, who in 1778 had blood drawn to help her give birth to her first daughter.

Another was King George IV of England who reportedly lost 150 ounces (4436 milliliters) of blood after the procedure in 1820, but miraculously managed to survive for another 10 years. In comparison to most other cases, Napoleon, Marie Antoinette, and George IV were extremely lucky, as bloodletting usually left a trail of death in its wake.

One of the first eminent deaths happened in 1492, when Pope Innocent VIII and the three boys who gave him blood all died from blood loss. In England, Charles II received venesection treatment after a stroke in 1685 and died after losing 24 ounces (709 milliliters) of blood, prompting the responsible physicians to flee for their lives. Charles’ niece, Queen Anne, later met her end in the same grisly way, after it caused her to have two fits and become unconscious. Even legendary composer Mozart could not escape death, dying in 1791 in Vienna after severe bloodlettings were prescribed to deal with renal failure.

In the US in 1799, president George Washington lost 79 ounces (2336 milliliters) of blood over 12 hours after being diagnosed with a “cold” and “mild hoarseness” by physician James Craik, resulting in a fatal case of acute epiglottis. Before his death in 1824 from bloodletting, which was meant to help him with encephalitis, noted literary figure Lord Byron decried: "Come as you are, I see a damned set of butchers. Take away as much blood as you will; but have done with it”.

As the examples testify, bloodletting was extremely dangerous, a fact recognized by 3rd century AD Arab queen Zenobia, who purposely used the process to kill Arab king Jothima Al Abrash. Yet in ancient Arabia, instead of it being a gory and degrading way to go to the grave, death by venesection was viewed as an honorable way to die, as blood would be collected in containers instead of spilled on the ground.

A physician administers leeches to a patient. (Wellcome Images / CC BY 4.0)

The Great Bloodletting Debate

During the 18th and 19th centuries, doctors began to question the efficacy of bloodletting. Veterinarians were the first to speak out against the practice, and in 1792 J. Thompson, a British vet, queried why such an excessive amount of blood should be allowed to be withdrawn without accurate measurements.

At the turn of the century, a particularly egregious case of bloodletting motivated 19th century clinicians to mount a stronger and more unified opposition. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was a bloodletting zealot who believed the it was key to eradicating sickness during the yellow fever epidemics of Philadelphia in 1793 and 1797. Rush was infamous for taking out massive amounts of blood from his patients which prompted criticism from his colleagues, who described his methods as “murderous” and his prescribed doses as only “fit for a horse.”

This led to a series of debates in the 1850s between Dr. William Alison and Dr. Hughes Bennet around the efficiency of bloodletting in the treatment of pneumonia. Dr. Alison held the old-school view that bloodletting was a beneficial practice, whereas Dr. Bennet believed that new medical knowledge discovered with the aid of the recently invented stethoscope and microscope proved that bloodletting was hindering more than it was helping a sufferer’s health. His study entitled “the restorative Treatment of Pneumonia” argued that mortality rates had improved in conjunction with the decreased use of bloodletting.

Bennet’s argument was further strengthened by the experiments of Dr. Pierre Louise, founder of medical statistics, whose study of pneumonia patients showed that excessive bleeding was followed by the death of one out of three patients in comparison to patients treated with Bennet’s restorative principle, where only four people died out of 129. Despite evidence that clearly showed the lethality of bloodletting, the debate persisted, and it would take nearly 100 more years for it to be slowly phased out of the physician’s toolkit.

“Pneumonia is one of the diseases in which a timely venesection may save life. To be of service it should be done early... the abstraction of from twenty to thirty ounces of blood is in every way beneficial,” claimed Sir William Osler in 1892 within his famous medical textbook Principles and Practices of Medicine. Osler was one of the last proponents of bloodletting.

Osler’s antediluvian advice could still be read in the last edition of his textbook, published as late as 1942, and in the 1950s Dr. D. P. Thomas recounted that medical students were still being instructed to apply leeches to patients.

The Legacy of Bloodletting

Despite being proven as more deadly than safe, bloodletting as a practice still continues in some corners of the world such as Morocco, Algeria, and Oman. In India today, patients visiting Muhammed Gayas at the Jama Masjid mosque in Delhi continue to hold the view that illness is caused by the blood going bad, a belief that started with Hippocrates and was developed by Galen over 2 millennia ago.

Yet while it took a long time to be dismissed during the transition from Renaissance to modern society, research at that time also indicated that bloodletting actually had a few beneficial uses, but only for a specific set of maladies.

In 1892, Valquez was the first to note its effectiveness against polycythemia, a blood disease that makes the blood viscous and thicker. Other discoveries showed that bloodletting was helpful against other conditions such as porphyria cutanea tarda and hemochromatosis which are both related to abnormal iron metabolism.

In the last 25 years, leeches have also been reinvented as useful biological tools in micro-surgery, as they release several convenient substances like anti-coagulants and proteinase inhibitors, and in re-implementation surgery, where they can help with the re-growth of fingers, ears, and toes.

- Five Bloodcurdling Medical Procedures That Are No Longer Performed … Thankfully

- The Many Ways Cancer Was Treated in the Ancient World

Perhaps bloodletting’s most important legacy was that it was a precursor to blood transfusions, which originated from Karl Landsteiner’s landmark discovery of different blood types in 1909, for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1930. The brutality of World War One presented this new method with the ultimate test, and many soldiers were saved by what gradually became accepted as a life-saving intervention.

At a meeting of the Royal Society of Medicine in April 1927, prominent physician Sir William Hale-White reminded those gathered that in 1840 a doctor had been charged with malpractice for refusing to apply venesection to a pneumonia patient. It illustrated the complicated peaks and troughs surrounding the changing ideas around bloodletting, and the unjust ways in which others had to suffer in order to achieve more advanced and superior methods of ensuring the wellbeing and health of afflicted patients.

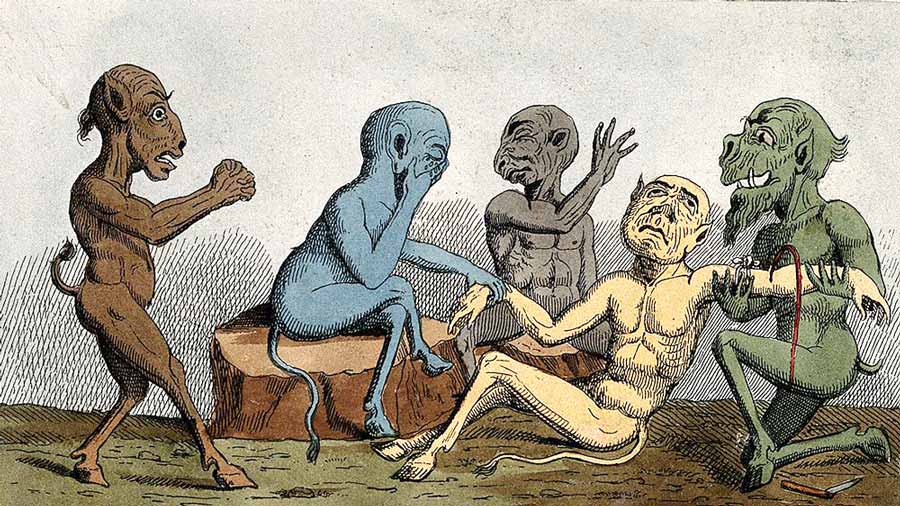

Top image: The bloodletting of a patient by a surgeon with three dismayed onlookers; represented by five faun-like demons. Source: Wellcome Images / CC BY 4.0

By Jake Leigh-Howarth

References

Albinali, H. A. H. 2004. Chairman’s Reflections: Blood-letting. Heart Views, 5:2.

Lexico. No date. “Bloodletting” in Lexico. Available at: https://www.lexico.com/definition/bloodletting .

Cohen, J. 2018. “A Brief History of Bloodletting” in History. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/a-brief-history-of-bloodletting

Cohut, M. 2020. “Bloodletting: Why doctors used to bleed their patients for health” in Medical News Today. Available at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/bloodletting-why-doctors-used-to-bleed-their-patients-for-health

Greenstone, G. 2010. “The history of bloodletting” in BCMJ, 52:1.

Parapia, L.A. 2008. “History of bloodletting by phlebotomy” in British Journal of Haematology, 143:4.

Thomas, D.P. 2014. “The demise of bloodletting” in The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 44:1.

Comments

If we think that this is all so primitive and horrific, you should see what the medical profession does today.