The Art of Courtly Love: 31 Medieval Rules for Romance

Love is the universal feeling. From the dawn of time, from the earliest epochs of man, and all throughout the rise and fall of world’s many civilizations, the concept of love drove the wheel of time forward. Love is not only familial – it is romantic too. In the early medieval period in Europe, love and romance in the high courts had to be done under a certain set of rules, and with a lot of class! And those very rules were perfectly presented in an enigmatic early medieval literary work: The Art of Courtly Love.

Man in love being lifted to his lady in a basket, from the Codex Manesse. (Public domain)

The Origins of the Art of Courtly Love

Love has been characterized in many different ways through time and different cultures often had unique views of it. Nevertheless, finding a suitable mate was, and still is, a major aspect of everyone’s life.

Men and women through the ages felt that universal, fundamental magnetism that inevitably fuels the incessant pulse of the Earth. For love, people were ready to do larger-than-life things. Wars were fought for love, riches squandered, and crimes committed. But not even love – such an inseparable aspect of who we are – is simple.

However, love is not always a mutual affair. In the Middle Ages especially, it could often be one-sided or completely nonexistent, especially in the high kingly courts. Marriages between heirs and princesses, lords and ladies, and kings and high-born women were often arranged purely for political and lucrative purposes. But where this was not the case, true love always found a way to blossom.

The courts of medieval France were perhaps the most advanced in Europe, setting new standards well before other courts picked them up. And the concept of courtly love was one such innovation. Romantic notions of love were originally spread by troubadours, poets and singers of the middle ages, famous for their bohemian lifestyles. In Provence, a historic region of France, the traditional musicians sang about the ways of the common man, but also propagated new social norms, many of which originated at the court.

- The Life and Times of the Notorious Medieval Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine

- Ancient Spells and Charms for the Hapless in Love

- Being Lovesick Was a Real Disease in the Middle Ages

Attempts to write such norms and social codes down are extremely rare in early medieval history, almost nonexistent. One of the very few such works, and perhaps the most important, is certainly the Tractatus Amoris & de Amoris Remedio, written by a man named Andreas Capellanus sometime around the year 1185 AD.

There are three sections in this remarkable book in which Andreas Capellanus devoted special attention to all aspects of love in the court. The first section deals with the acquisition of love and its nature; the second tackles the question of how to retain love; while the third part talks about rejection and the end of love.

Medieval duke and ladies in a garden. (British Library / CC0)

Poitiers Heat: Romance in the High Class

Capellanus’ famous book is also known variously as simply De Amore (“About Love”), or De Arte Honeste Amandi (“The Art of Courtly (Virtuous) Love”). Scholars agree that it was most probably written sometimes between 1185 and 1190 AD, and by all means intended for the court of Phillip II Augustus, King of France from 1180 to 1223 AD. Scholars say that it was seemingly written at the behest of princess Marie of France, Countess Consort of Champagne, in Poitiers.

Marie was the daughter of the preceding French King, Louis VII. However, some hints in the original text might indicate that it was written around 1184 when the King of Hungary, Béla III proposed to marry Margaret of France, the sister of Marie of Champagne, a proposal which was accepted after 1186.

Nevertheless, the “codified” rule for romancing gathered in the Art of Courtly Love soon began spreading around, mostly thanks to the work of the tireless troubadours of Provence. Andreas Capellanus seems to have drawn great inspiration from writers of the antiquity, chiefly Ovid and Plato.

For example, Ovid was one of the most famed of Roman authors, and his works such as Amores (“The Loves”), Remedia Amoris (“The Cure for Love”), or Ars Amatoria (“The Art of Love”) could have easily served as a firm basis for Capellanus’ masterwork. On the other hand, when his Art of Courtly Love is studied in depth, the slight touches of Plato’s philosophy becomes easily noticeable. What is more, we can recognize a critical, and almost philosophic influence akin to those classical masters, in the very first sentence of Capellanus’ work:

“Love is a certain inborn suffering, derived from the sight of and excessive meditation upon the beauty of the opposite sex, which causes each one to wish above all things the embraces of the other and by common desire to carry out all love’s precepts in the other’s embrace.”

This sentence is much akin to something written by Plato. Capellanus’ clearly relies on the classical Greek concept of eros, stating that love is an “inborn suffering” or evidence of human imperfection and lack of purity, a clear outcome of our insufficiency. Plato’s view of love was highly conceptual and philosophic, straying far from the worldly, physical aspect.

But Andreas Capellanus takes these classical concepts to a new level, showing clear signs of maturity that came with the passing ages. Capellanus combines the philosophical concepts of Plato and the more distinct sexual realism of Ovid, utilizing them to deliver his own, unique work that attempts to unify both the courtly and religious aspects, in order to deal with all things related to love.

Capellanus’ book De Amore is one of the most unique literary works of the European medieval era. (Public domain)

The Nitty-Gritty of Love: A Guidebook for the Clueless Lover

The book consists of a brief preface, which is then followed by “books”, or chapters, one, two, and three. In the preface, Capellanus shows an almost humorous, somewhat witty, and fully relaxed approach to connecting with the reader, utilizing the figure of a fictional protagonist, a young man he calls Walter, who is addressed by the author himself. In the preface, Walter is seemingly freshly fallen in love, perhaps even for the first time. Capellanus describes him as the “new soldier of love, wounded with a new arrow.” He goes on to shape him as clueless in how to deal with the feeling of love, having no idea how to “govern the reins of the horse that soldier himself rides nor to be able to find any remedy himself.”

Seemingly intending for the reader to connect with the character of Walter, Capellanus then promises to teach the young man all that he needs to know about love: about “the way in which a state of love between two lovers may be kept unharmed, and likewise how those who do not love may get rid of the darts of Venus that are in their hearts.”

Book one proceeds to tackle the different aspects of love in a manner that is very unique, and certainly advanced for the medieval period in which the work was written. Andreas Capellanus offers nine fictional dialogues, all between men and women of all social classes ranging from bourgeoisie to royalty of the court. The dialogues are written in such a way as to offer reasonable arguments in relation to common love issues and situations – at least those common for the era.

From these dialogues we can quickly understand the main principles that generated distinction amongst the men of medieval France. Accomplishments in life were the great contributor to success in romance. In most dialogues, the male suitors either seek the love of a woman as “reward” for their great deeds, while those of poorer classes seek to distinguish themselves in order to achieve the same goal.

Depiction of count Kraft II of Toggenburg, climbing a tower to visit his lady, from the Codex Manesse. (Public domain)

In the second book, Capellanus tackles the next phase of romance: the maintaining of love and the looming possibility of its subsequent end. After this segment, the author reflects on the twenty-one judgments of love, all of which he attributes as quotes of great ladies of the era. Some of those ladies are Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife of King Louis VII, and mother of Marie of Champagne, then Marie herself (once more alluding to the possibility that she ordered the book written), as well as the niece of Eleanor, Countess of Flanders Isabelle of Vermandois, and also Viscountess Ermengarde of Narbonne.

The final portion of the second “book” lists out thirty-one rules of love, which mostly resemble guidelines. These rules are as follows:

I. Marriage is no real excuse for not loving.

II. He who is not jealous cannot love.

III. No one can be bound by a double love.

IV. It is well known that love is always increasing or decreasing.

V. That which a lover takes against the will of his beloved has no relish.

VI. Boys do not love until they reach the age of maturity.

VII. When one lover dies, a widowhood of two years is required of the survivor.

VIII. No one should be deprived of love without the very best of reasons.

IX. No one can love unless he is impelled by the persuasion of love.

X. Love is always a stranger in the home of avarice.

XI. It is not proper to love any woman whom one would be ashamed to seek to marry.

XII. A true lover does not desire to embrace in love anyone except his beloved.

XIII. When made public love rarely endures.

XIV. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

XV. Every lover regularly turns pale in the presence of his beloved.

XVI. When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved his heart palpitates.

XVII. A new love puts to flight an old one.

XVIII. Good character alone makes any man worthy of love.

XIX. If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely revives.

XX. A man in love is always apprehensive.

XXI. Real jealousy always increases the feeling of love.

XXII. Jealousy, and therefore love, are increased when one suspects his beloved.

XXIII. He whom the thought of love vexes eats and sleeps very little.

XXIV. Every act of a lover ends in the thought of his beloved.

XXV. A true lover considers nothing good except what he thinks will please his beloved.

XXVI. Love can deny nothing to love.

XXVII. A lover can never have enough of the solaces of his beloved.

XXVIII. A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved.

XXIX. A man who is vexed by too much passion usually does not love.

XXX. A true lover is constantly and without intermission possessed by the thought of his beloved.

XXXI. Nothing forbids one woman being loved by two men or one man by two women.

An Unlikely Conclusion: Getting Rid of the Darts of Venus

The Art of Courtly Love culminates with the third book. This is also the shortest one, and could very well serve as a conclusion to the whole piece. It deals with rejection, as the title clearly implies: “Rejection of Love.” As if wishing to ease the sorrows of spurned men, Capellanus descends in this book into an all-out slander of women, citing their numerous negative traits. He goes on to describe women as completely untrustworthy, vain and jealous of other women and their beauty – “even their daughter’s” – as always unfaithful in love, fond of gossip, slanderers and deceivers, easily swayed and endlessly greedy, and disobedient. Capellanus takes in account the myth of Eve as the original example of their negative aspects.

This conclusion to the book is directly tied in to the promise from the introduction. Capellanus does indeed instruct the reader on how to “get rid of the darts of Venus that are in their hearts.” It appears that the solution is by simply not indulging into affairs of the sort described in the book. He then concludes his work in a predictable manner, once more showcasing the inclination to the philosophical works of Plato. He states that abstinence is the route to choose, stating that through abstaining from the affairs of courtly love, one can “win an eternal recompense and thereby deserve a greater reward from God.” In this final chapter, Capellanus clearly discredits all that is written within the book. This has let to modern scholars characterizing this didactic work as a mockery.

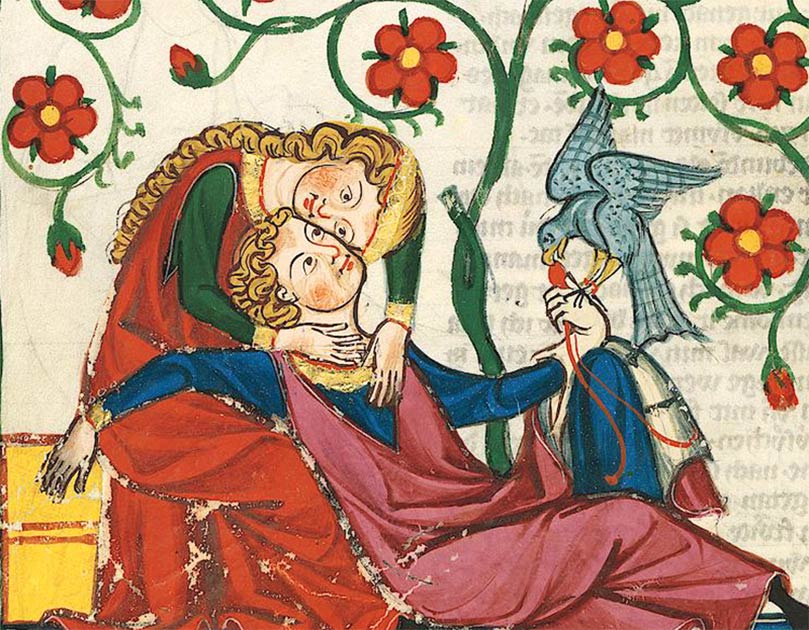

Lovers in the Codex Manesse. (Public domain)

To Love or Not to Love

De Amore is certainly one of the most unique literary works of the European middle age, and provides us with a crucial insight into the social norms of the (mainly French) upper class of the period. However, it is also important for the study of courting traditions, the history of romance, and the scholarly approach to the same. And although Andreas Capellanus’ true identity remains a mystery, his work nonetheless withstood the test of time as one of the most advanced literary works to come from the early Middle Ages.

Top image: The Art of Courtly Love Is an early medieval literary work by Andreas Capellanus which gives us crucial insights to the social norms of love in the courtly classes of the Middle Ages. Source: Public domain

References

Baldwin, J. 2015. The Language of Sex: Five Voices from Northern France around 1200. University of Chicago Press.

Evergates, T. 2018. Marie of France: Countess of Champagne, 1145-1198. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Monson, D. 2005. Andreas Capellanus, Scholasticism, and the Courtly Tradition. CUA Press.

Singer, I. 2009. The Nature of Love, Volume 2: Courtly and Romantic. MIT Press.