A Failed #MeToo Moment: Just How Horrible Being An Ancient Roman Actress Could Be

When an actress in ancient Rome was brutally gang-raped by a group of young men who’d come to see her show, she started a very public battle for justice. The story of her fight and her failure is usually nothing more than a footnote in the history of important men. But it actually reveals a dark side to what it meant to be a woman 2,000 years ago.

The woman, whose name has been lost to time, was a mimae, a sort of silent comedian popular in the days of the Roman Empire. She’d been performing in a countryside theater to a modest crowd in Atina, expecting nothing more than a few laughs. But before she’d even left the theater, a gang of men in the audience knocked her to ground, pinned her down, and brutalized her.

She fought for justice. She pressed charges against the men who’d attacked her and tried to use the scandal to destroy the political career of one of her rapists. But the courts of Rome just laughed at her.

- The Black Sheep of the Empire: Actors and Actresses in Ancient Rome

- Theodora: From humble beginnings to powerful empress who changed history

- Phryne, The Ancient Greek Prostitute Who Flashed Her Way to Freedom

Beating, pinning down, and gang-raping an actress, the courts of ancient Rome ruled, was simply acting “in accordance with a well-established tradition at staged events.”

“O how elegantly must his youth have been passed,” her attacker’s lawyer, Cicero, quipped during the trial, “when the only thing which is imputed to him is one that there was not much harm in.”

It’s a horrifying story that rings disturbingly familiar today. But it’s more than just a single incident in history – it’s something that happened again and again; a glimpse into the horrible lives Roman actresses endured for hundreds of years.

Mosaic depicting masked actors in a play: two women consult a "witch". Roman mosaic from the Villa del Cicerone in Pompeii, now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Naples). ( Public Domain )

The Horrifying Treatment Of Actresses In Ancient Rome

Women were rarely allowed to perform in respected acting troupes. Like the theaters of Shakespeare’s time, the female roles were usually taken by men dressed up in women’s clothes. There were a few exceptions – in the empire’s later years, a small handful of women managed to land respectable roles – but those were rare. Most women never got the chance to perform on a respectable stage.

Instead, most women were relegated to lives as dancers and “mimae” – mimes who would put on parodies of myths and heroes. It wasn’t an easy job. These women started training when they were small children, and they’d have to spend years honing their craft.

But the men in the audience treated them as little more than prostitutes. Men would regularly yell at the stage, demanding that the actresses take off their clothes – and, over time, most of the actresses would comply.

‘The Empire of Flora’ (circa 1743) by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. ( Public Domain ) Based on Ovid's account of the Floralia, a festival to the Roman goddess Flora involving prostitutes.

There are no accounts of these performances that talk about the actresses’ clever wit or their ability to conjure up subtle emotions – instead, they’re usually described as something a bit closer to pornography. The satirist Horace quipped that “[what] you have with actresses, you have with common strumpets”, while the poet Martial described a show by saying that the women “would have made Hippolytus himself a masturbator.”

A Life They Couldn’t Escape

To be fair to these men, the women essentially were sex workers. Most of them were something closer to modern strippers than actresses, expected to titillate more than amuse. One of the most famous, for example, made a name for herself by putting on a parody of the story of “Leda and the Swan” in which geese ate grains off her body until she was completely exposed.

For women in Rome, though, this was the only theater they were allowed to enter. And usually they weren’t there by choice. Most were slaves, stuck in a life of what the Romans called “theatrical servitude”. They had no choice but to perform. If an actress ran, her owner had every right to drag her back and force her back onto the stage.

The Slave Market by Gustave Boulanger's 1886. ( Public Domain )

But that didn’t mean that every actress in Rome settled into a life of mediocrity, exploitation, and sexual abuse. Plenty of the women wanted more – and they fought hard to get it. They joined actresses’ guilds, pushed for better roles, and a handful won enough of a reputation that earned a respectable income performing on the stage.

At least one woman got it. A young girl named Eucharis performed so well that it was she said that she was “taught as if by the Muses’ hands.” Her talent won her her freedom. She got roles in classic Greek plays and a place on the stage in front of audiences of nobles, and she took pride in the respect she’d earned.

Theodora is said to have worked as a prostitute and performed on the stage in Constantinople. ‘The Empress Theodora at the Colosseum’ by Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, 1845-1902. (Public Domain)

Her story, though, was an exception rather than the rule. Most actresses toiled on dirty stages stripping for drunken men for their whole lives, without any chance of escape.

An Actress’ Battle for Dignity

The woman who was gang-raped at that show in Atina was like most of the actresses in Rome. She was a mimae, a silent comedian who performed in satires, playing in a small town to a crowd of drunken men.

When she was attacked, nobody seemed to care. Nothing happened to the men who attacked her, and she had to watch as one, Cnaeus Plancius, rose up to the curule aedileship, one of Rome’s highest political offices.

A rare painted depiction of Roman men wearing togae praetextae participating in a religious ceremony, probably the Compitalia; note the dark red color of their toga borders. Fresco on a building outside Pompeii. (Public Domain)

When she told the world what he’d done to her, she surely saw herself as a woman fighting for justice. After everything this man had done to her, he hadn’t suffered consequences at all. She’s been stuck in a dirt road town, likely living as a slave, struggling through the trauma of his attack, while honor after honor had been put on the man who abused her.

To the men of Rome, though, her rape was barely even worth mention. Planicus’s lawyer, Cicero, only deigned to waste three sentences of breath talking about it. He didn’t even deny that he’d done it; instead, he just wrote it off as something “there was not much harm in.”

As far as the men of Rome were concerned, it was her own fault. She was asking for it, purely by being an actress.

Fresco depicting a seated woman, from the Villa Arianna at Stabiae, 1st century AD, Naples National Archaeological Museum. (Carole Raddato/CC BY SA 2.0)

And history sided with the men. Her story’s been passed down for more than 2,000 years, but not as a story of a woman wronged. Instead, it’s been remembered as a small footnote in the story of Cnaeus Plancius, an innocent Roman politician whose enemies tried to discredit him with trivial complaints, or as an example of Cicero’s masterful rhetoric.

- Swans Fat, Crocodile Dung, and Ashes of Snails: Achieving Beauty in Ancient Rome

- The Legendary Prophetess Veleda: A Secret Weapon Against the Romans

- Paying for Services: Illicit Brothel Coins of Pompeii Show What’s on The Menu

Barely a word in any history book has been expended to the woman he attacked: the actress he and his friends brutally raped. Her fight for justice, in most ways, failed.

But just by fighting, she proved something – even if the world wouldn’t fully understand it for thousands of years: she wouldn’t accept it.

Funerary Portrait of a Woman, about 138-192 AD, Roman Empire, Antonine, encaustic on linen - Cleveland Museum of Art. (CC0)

She might have had a degrading job with a bad reputation, but she never wanted that to happen to her. The men who attacked her got free, but she proved that they were wrong about her. She never allowed or wanted it to happen.

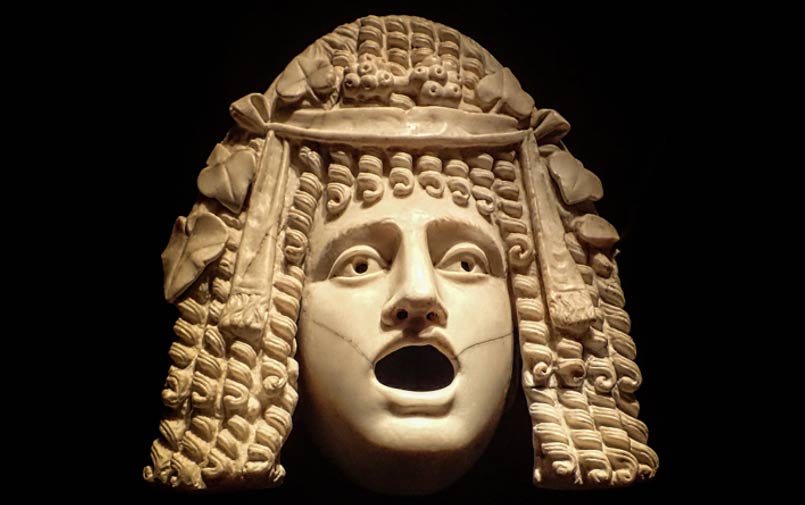

Top Image: Marble theater mask depicting a woman from a popular Roman tragedy Pompeii 1st century AD. Source: Mary Harrsch/CC BY NC SA 2.0

By Mark Oliver

References

Cicero, M. Tullius. For Plancius. Trans. C. D. Young. George Bell & Sons, 1891. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0020:text=Planc.

Craig, Christopher P. “Cicero’s Strategy of Embarrassment in the Speech for Plancius.” The American Journal of Philology. 111 (1), 1990, pp. 75-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/295261?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Dill, Samuel. Roman Society in the Last Century of the Western Empire. MacMillan and Co. 1921. https://books.google.com/books?id=Rwm7DkKYRnEC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Duncan, Anne. “’It Wasn’t Rape-Rape’: Roman Attitudes Toward the Sexual Availability of Mimae.” Univeristy of Nebraska-Lincoln. 2018. https://camws.org/sites/default/files/meeting2018/abstracts/157.mimae.pdf

Evans, John K. “War and Working Women.” War, Women and Children in Ancient Rome. Routledge, 1991. https://books.google.com/books?id=sL7KAgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Horace. The Works of Horace. Harper & Brother, 1863. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:abo:phi,0893,004:1:2

Lactantius. Divine Institutes. Trans. William Fletcher. Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/07011.htm

Lefkowitz, Mary R. and Maureen B. Fant. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation. The John Hopkins University Press, 2005. https://books.google.com/books?id=LV-FPLMeHgoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Plutarch. “Sulla.” Plutarch’s Lives. Trans. Bernadotte Perrin. Harvard University Press, 1916. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plut.+Sull.+36&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0064

“Priapeia.” Trans. Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton. 1890. http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/priap/priapeia.htm

Procopius. “Chapter IX”. The Anecdota or Secret History. Loeb Classic Library, 1935. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/procopius/anecdota/9*.html

Comments

Weakest of males/females have been used and abused since our time has begun, poisoning was the equalizer when karma runs too slowly

There is strong evidence that women actually never allowed such treatment but thank you for pointing out that “if she were an actress, those types were expected and accepted their position to performing..” I read it, read on through the article and had to go way back to find YOUR remark. “to be fair to the men…..these women….” You actually tried to justify your woohoo thoughts. STOP just be quiet.

If these women were “mimae,” wasn’t she a “mima”?

CBSanford