Mokomokai: Preservation of the Tattooed Maori Heads of New Zealand

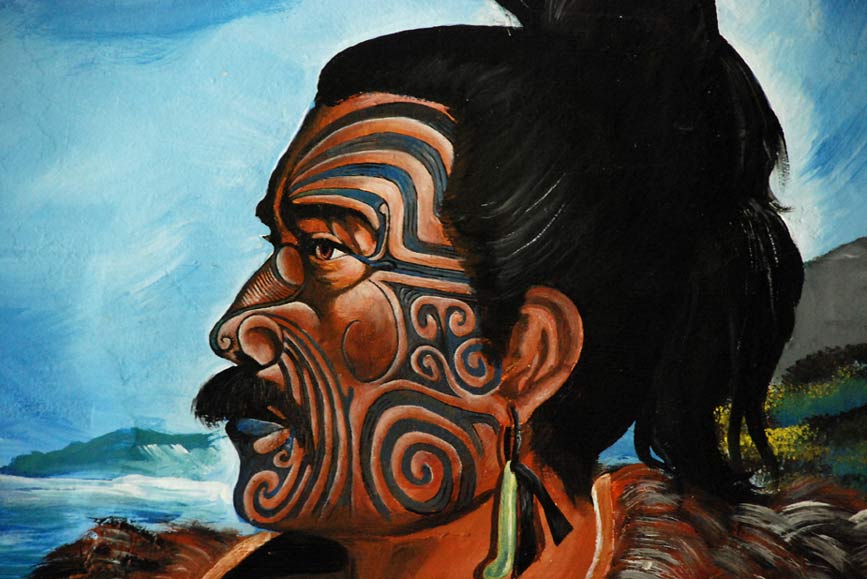

Mokomokai are preserved heads that are produced by the Māoris of New Zealand. These are not just any heads, but heads that have been decorated by moko. Moko is a traditional art form practiced by the Māoris, and produces facial and bodily markings that are permanent. In the past, these markings represented high social status in Maori culture, and it was generally men who had the full facial moko.

Mataora & Niwareka – The Legendary Beginning of Mokomokai

The moko is produced by carving a person’s skin with an uhi (a chisel-like tool), and then filling the grooves with ink. The origins of this practice can be found in the ancient Māori tale of Niwareka and her husband, Mataora.

In this story, the Tā moko was not known, and markings were only painted onto the skin. One day, Niwareka was mistreated by her husband, and she fled to her father’s people in Rarohenga, the Underworld. Mataora pursued her, hoping to persuade his wife to return. When he arrived at Rarohenga, Mataora’s face paint was smeared by his sweat, causing laughter amongst Niwareka’s people. This was because the people of Rarohenga painted their faces using the art of Tā moko. Mataora begged for his wife’s forgiveness, and asked his father-in-law to teach him this art. After this, Mataora and his wife returned home, bringing this knowledge with them.

The tale of Mataora & Niwareka. (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Production of a Mokomokai

Traditionally, male facial moko was considered as a mark of adulthood, and each line is said to attest to a man’s courage, as the process of producing these intricate patterns is extremely painful. It has also been said that in Māori culture, the head is considered as the most sacred part of the body, and the moko served to enhance its sacredness. The value of the moko remained even after death, and, in the past, heads decorated with moko were usually preserved, and are known as mokomokai.

- Tattooed Maori head returns to New Zealand from British Museum

- Creation Myth of the Maori – New Zealand

Maori Moko, scanned from John Rutherford: The White Chief (pre-1923) (Public Domain)

The process of making a mokomokai would begin with the severing of a deceased person’s head. This would be followed by the removal of the brains and eyes. The orifices of the head would then be filled with flax fiber and gum. Next, the head would be boiled or steamed, before being smoked over an open fire. After this, the head would be dried under the sun for several days. Finally, the preserved head would be treated with shark oil. Depending on whose head it was, it would have been treated differently.

Honor and Trophy

Firstly, family members, as well as important and revered individuals within a Māori would normally have their heads turned into mokomokai when they died. By turning their heads into mokomokai, the dead would continue to be honored by their families and communities. Additionally, this was a way for the deceased, especially dead leaders, to maintain their involvement in the community, even after death. As objects of honor, these mokomokai were kept by their immediate families in ornately carved boxes.

A Maori Mokomokai preserved head (Propnomicon)

On the other hand, mokomokai were also produced as trophies of war. During a battle, warriors would try to secure the head of a fallen enemy. Once the battle was over, the enemy’s head would be turned into a mokomokai, and then displayed on a post as an object of derision. After that, the head would be put away, and brought out on important occasions, when stories of the victory would be retold, and insults hurled at the head. Although this served as a great insult to the fallen warrior and his community, such mokomokai could also be used during peace negotiations, as the heads could be returned in exchange for something else.

Demand for Mokomokai

When Europeans arrived in New Zealand, a demand for the mokomokai was created, as they were seen as objects of curiosity. Usually, the mokomokai of enemies were sold to the Europeans, perhaps as a further insult to the fallen.

The Musket Wars during the 1st half of the 19th century saw the sales of mokomokai peaking. During this period, there was a demand amongst Māori groups for European firearms and ammunitions. It is reported that one of the most effective ways to acquire these weapons was to purchase them with mokomokai. In 1831, however, the mokomokai trade was banned by the Governor of New South Wales, General Sir Ralph Darling, in Sydney (this was the main route for the trafficking of mokomokai to Europe).

Mokomokai in a museum showcase (maori.maori.nz)

Nevertheless, a large quantity of these preserved heads have been exported out of New Zealand, and it has been estimated that hundreds of them are now kept in European and American museums, hospitals and private collections. In a briefing note to the Trustees of the British Museum, dated to the 23rd of November 2006, for example, it is written that the British Museum possessed seven preserved heads.

H. G. Robley and his mokomokai collection. (Public Domain)

Today, there are those amongst the Māori who want these heads to be repatriated to their community. It has been reported that between 1987 and 2009, about 68 mokomokai have been repatriated to the Māoris, thanks to the Te Papa’s repatriation team. Still, with so many more of these artifacts in Europe and America, it is likely that the process of repatriation will continue for some time.

Featured image: A Māori warrior. Source: Geof Wilson/ CC BY NC ND 2.0

By Ḏḥwty

References

Johnson, K., 2014. Shrunken Heads: Yesterday And Today. [Online]

Available at: http://odditiesbizarre.com/shrunken-heads-yesterday-today/

Meghan, 2014. Mokomokai: The Preserved Heads of Maori Tribespeople. [Online]

Available at: http://www.cvltnation.com/mokomokai-the-preserved-heads-of-maori-tribespeople/

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, 2016. The Origins of Tā Moko. [Online]

Available at: http://www.tepapa.govt.nz/Education/OnlineResources/Archive/Moko/Pages/Origins.aspx

Sunday Star Times, 2009. The trade in preserved Maori heads. [Online]

Available at: http://www.stuff.co.nz/sunday-star-times/features/feature-archive/212741

Te Awekotuku, N., 2012. The rise of the Maori tribal tattoo. [Online]

Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19628418

The British Museum, 2006. Human Remains from New Zealand, Briefing note for Trustees. [Online]

Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/00%2012%20Briefing%20note%20to%20Trustees%20dated%2023.11.06.pdf

Victoria University of Wellington, 2015. Mokomokai: Preserving the Past. [Online]

Available at: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-TeIMoko.html

Yates, D., 2013. Toi moko. [Online]

Available at: http://traffickingculture.org/encyclopedia/case-studies/toimoko/