16 Bizarre, Impressive and Hilarious Funerary Masks of the Ancient World

Throughout history, many cultures and civilizations created funerary masks as part of their burial customs. The masks were used to represent a deceased individual, to honor them, and to cover their faces at the time of burial. Sometimes, they were seen as a connection between the physical world and the spirit world or afterlife. In some cultures, funerary masks were made to protect the deceased by frightening away malevolent spirits. They are distinct from death masks, which are an impression taken of the face of a person who has died, to preserve their likeness.

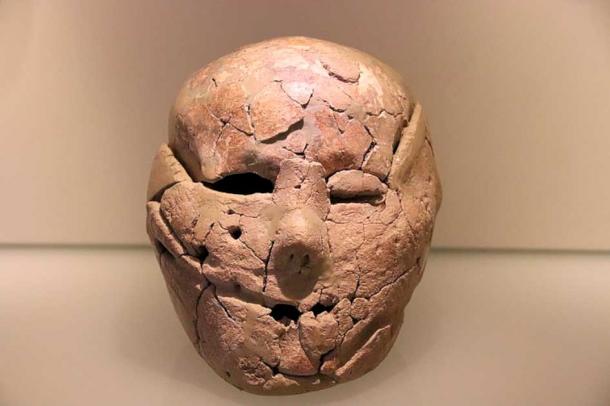

The earliest known funerary masks are the Jericho plastered skulls, which date back around 11,000 years. Since that time, funerary masks have taken on a variety of different forms, from impressive, golden masks for elite members of society, to painted plaster portraits and cartoon-like, smiling faces.

Funerary mask, 500 BC – 500 AD, Condorhuasi-Alamito. The Condorhuasi-Alamito peoples were llama pastoralists in the area that is now the Catamarca province of Argentina. (Met Museum / Public Domain)

An almost cartoon-like funerary mask made with wood, gold, cloth and shell, 13th–15th century AD, Ica, Peru (Met Museum / Public Domain)

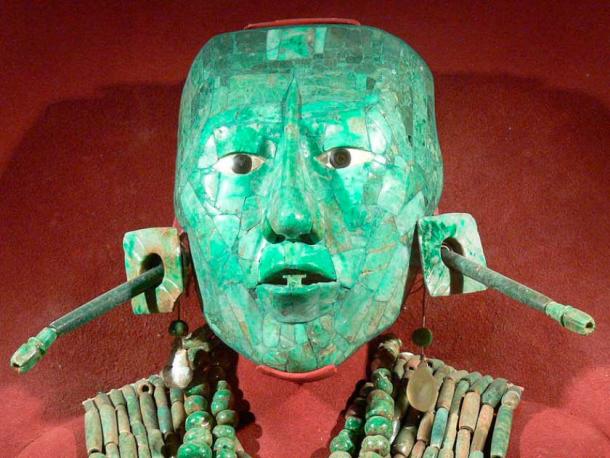

Jade funerary mask of Maya king Pakal of Palenque (Pakal the Great), 7 th Century AD, Mexico (Wolfgang Sauber / CC by SA 3.0)

Funerary Mask, 10th–12th century, Lambayeque (Sicán) culture, Peru. This mask, made of hammered sheet gold alloy and covered in red pigment, once adorned the body of a deceased ruler on Peru’s north coast. (Met Museum / Public Domain)

Mummy mask made with cotton, nut shells and human hair, Callao, Peru (Trustees of The British Museum / CC by SA 4.0)

- The eerie masks that preserve history and breathe life into the dead

- 10 Sacred Masks for Hunting, Ritual, Shame and Death

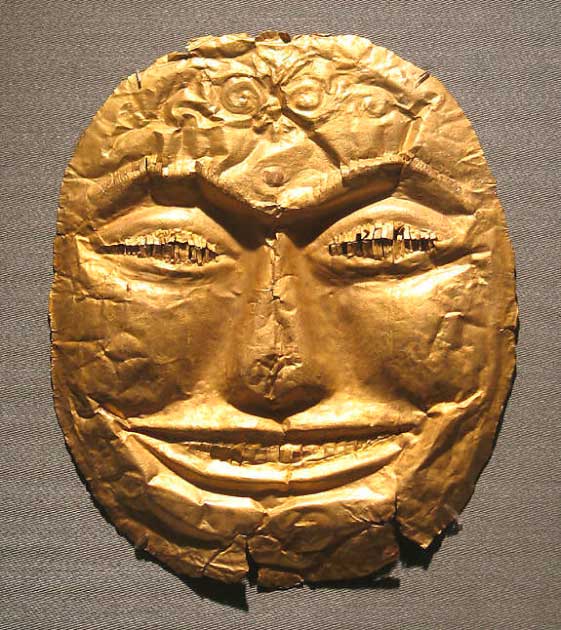

A very happy-looking, gold funerary mask, 14th century, Indonesia (Java, Majapahit) (Met Museum / Public Domain)

Plastered mummy mask, 100-120 AD, Roman period, Egypt (Trustees of The British Museum / CC by SA 4.0)

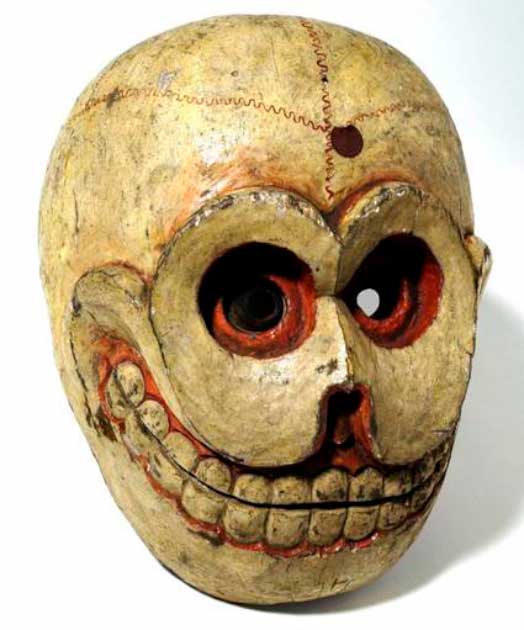

Skull funerary mask, Bhutan (Wellcome Collection / CC by SA 4.0)

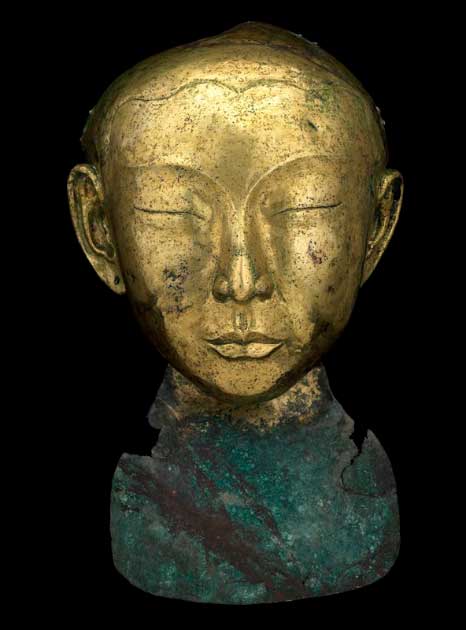

Funerary mask of a young woman from the semi-nomadic Khitans, the Liao dynasty (907-1125), China (Artsmia / Public Domain). The Liao often used gold or gilt bronze funerary masks in burials of important individuals. It is thought these masks were portraits of the deceased.

Plastered Skull, c. 9000 BC Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel. (Gary Todd / CC0). The plastered skulls of Jericho are the oldest funerary masks in the world. The skulls of their dead were removed and covered with plaster in order to create very life-like faces, complete with shells inset for eyes. The flesh and jawbones were removed from the skulls in order to model the plaster over the bone and the physical traits of the faces seem specific to individuals, suggesting that these decorated skulls were portraits of the deceased.

Funerary mask of a woman, ca. 1427 BC–1390 BC, New Kingdom, Egypt. The owner was probably the wife of an overseer of builders named Amenhotep (Met Museum / Public Domain)

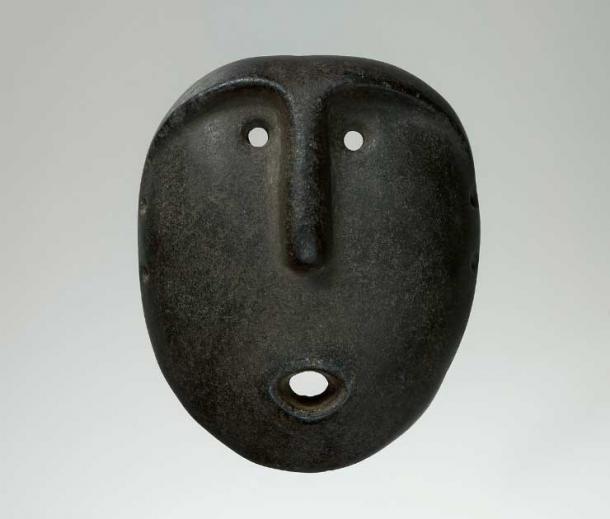

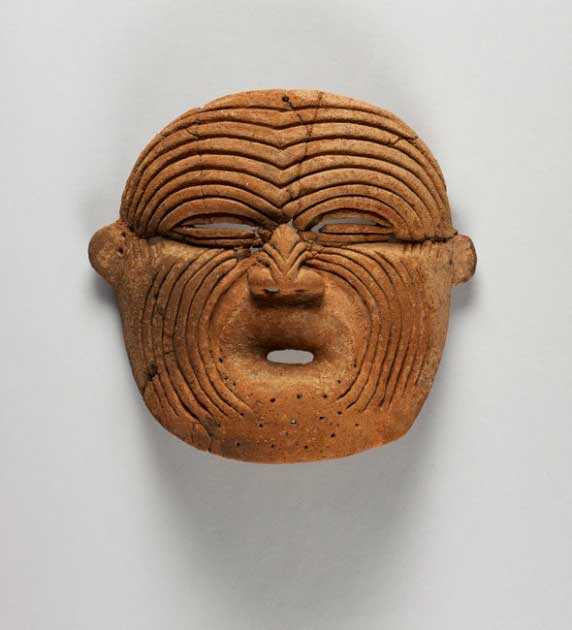

Stone pre-Columbian funerary mask, 250 – 450 AD, Teotihuacan, Mexico (The Vilcek Foundation). The mask would have been placed over the face of a deceased, elite individual and attached with string through the holes in the ears.

Funerary mask, 5th–1st century BC, Calima (Ilama), Colombia. Calima masks of the Ilama era are often flat, with generic details of the human face. On this example, the features are individualized with puffy bags beneath the eyes, a broad nose with flared nostrils, big, round, bulging cheeks, and a fat-lipped open mouth. (Met Museum / Public Domain)

Funerary mask made from plaster, 250–300 AD, Roman Period, Egypt (Met Museum / Egypt)

Colima funerary mask made with light green stone, 300 BC – 300 AD, Mexico (The Vilcek Foundation)

Ceramic funerary mask, 1000 BC – 100 AD, Calima, Colombia (Princeton University Art Museum)

Top image: Skull funerary mask, Bhutan (Wellcome Collection / CC by SA 4.0)

By Joanna Gillan

Comments

It just seems to me that a spiritual culture as such would be unlikely to believe that a simple mask would protect from the spirit realm.. most that had a definite spirit aspect respected the power etc of such.. but again.. who really knows

infinitesimal waveparticles comprise what we call home the earth

manipulatable by thought ability supressed in humans since birth

So if funerary masks(obsured etymology aside) are a thing across diverse culturae and belief systems.. this would imply a memory ( or at the least a semi logical reasoning).. ok they scared away evil spirits so they couldnt inhabit the dead body. Maybe some.. but is that the explanation for a just-antidiluvian practice that just happened to survive for thousands of years in various forms?

infinitesimal waveparticles comprise what we call home the earth

manipulatable by thought ability supressed in humans since birth

Okay, let’s go back, review things. The word funeral, comes from the latin for torch, as in funeral pyre, which was the ancient way of sending off the dead to the heavens. Should have NOTHING to do with people who were buried in rubble.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.