Words from the Ancient Past: The Sogdian Ancient Letters

The Sogdians were a people of Iranian origin who lived in the fertile valleys of Central Asia between the sixth century BC and tenth century AD. The secret to the Sogdians’ success was their knack for commerce. Building cities in what is today Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the Sogdian merchants became vital go-betweens for trade on the Silk Road. The legacy of these people is also preserved in the fragments of writings that remain with us today. Many of the documents are translations of Buddhist scriptures. More intriguingly, there are also five nearly-complete personal letters that paint a vivid picture of what life was like for the ordinary people living in a vast trade society.

Sogdians on an Achaemenid Persian relief from the Apadana of Persepolis, offering tributary gifts to the Persian king Darius I, 5th century BC (public domain)

The five letters were discovered in 1907 by Aurel Stein, a famous British archaeologist, in the ruins of a Chinese watchtower that guarded the city of Dunhuang (an administrative and cultural center modern-day Gansu Province). The tower stood at the western approaches of the city, which would have been an important stop on Silk Road trading routes. These letters “are the earliest substantial examples of Sogdian writing and thus provide extremely important information about the early history of the Sogdian diaspora along the eastern end of the silk route” (Sims-Williams, 2004). Some experts theorize that the letters had been confiscated by the Chinese officials at a time when Chinese control over this region was under threat; others suggest that they were abandoned in the hasty flight of a deliveryman fleeing from the city.

The letters were found outside Dunhuang, pictured (sand and tsunamis / flickr)

Each letter had evidence of being folded and refolded several times; they also bore the names of the senders and intended recipients on the outside. At least two were written by people in Dunhuang. The letters are believed to have been part of a ‘mailbag’ traveling among the major cities of the region. Letters nos. 2 and 5 concern the commercial activity of the writers, who were most likely merchants or their representatives abroad. The author of Letter 2 lived in Jincheng (modern-day Lanzhou, also in Gansu province), a town built at the entrance to a pass between the southern mountains and the northern deserts that ultimately leads to Dunhuang, a gateway known as the Hexi Corridor. The author was a member of the Sogdian diaspora living in China; he was a representative of a wealthy Sogdian merchant in Samarkand. He wrote to the home office to relate the recent attacks by the Huns on the Chinese cities of Yeh and Luoyang. “The last emperor, so they say, fled from Luoyang because of the famine and fire was set to his palace and to the city, and the palace was burnt and the city [destroyed]. Luoyang is no more, Yeh is no more! [...] And, sirs, if I were to write to you about how China has fared, it would be beyond grief: there is no profit for you to gain from it [...] [in] Luoyang... the Indians and the Sogdians there had all died of starvation” (Sims-William quoted in Vaissière, 2003). The letter also expresses concerns involving the distribution of some money that the author had deposited back at home.

Sogdian script on the Bugut Inscription (585), central Mongolia. Sogdian is the distant ancestor of the Mongolian script. (public domain)

Letter 5 originated in Guzang, located within the Hexi Corridor northwest of Luoyang. The intended recipient “may have been resident in Khotan, an important town along the southern silk route just before it crosses the Pamir Mountains to reach the oases of Transoxania, the region between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers” (Sims-Williams, 2004). This letter also discusses the difficult conditions wrought on China by the Huns. This author seems to be in a more perilous position than the author of Letter 2: he complains that his commercial partner has just abandoned him.

Huns in battle with the Alans, an Iranian nomadic pastoral people of antiquity. An 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger (public domain)

Letters 1 and 3 are of a different nature. They were written by a woman named Mewnai (“tiger cub”) whose husband Nanaidat (“created by the goddess Nanai”) had abandoned her in Dunhuang. The first letter is addressed to Mewnai’s mother, Catis; the third letter is addressed to Nanaidat and written on behalf of Mewnai and Nanidat’s daughter, Sen. Both letters describe how Mewnai and Sen have been living in Dunhuang for over 3 years without any word from Nanaidat. As they have run out of clothes and money, Mewnai begs to be allowed to return to her parents’ home. However, the closest relative of her husband, a man named Farnxund, is refusing to let them leave. Mewnai writes that a priest has offered to provide the mother and daughter with a camel and escort; he implores Mewnai to go home. In the first letter, Mewnai asks her mother if it is okay to agree to the priest’s offer. In the other letter, Mewnai and Sen say that if Nanaidat does not speak up soon, they will be sold by Fernxund into the servitude of the Chinese. There is a good chance Nanaidat died while out on the dangerous trade roads. In any case, there is no evidence of what ever happened to this small Sogdian family.

An 8th-century figurine of a Sogdian man wearing a distinctive cap and face veil, possibly a camel rider or even a Zoroastrian priest engaging in a ritual at a fire temple, since face veils were used to avoid contaminating the holy fire with breath or saliva (public domain)

Much of what is known about the Sogdians comes from Chinese chronicles in which the phrases ‘inland Silk Road’ and ‘Sogdian trading network’ are all but synonymous. Other references to the people come from Greek, Indian, Arabic, Byzantine, and Armenian sources. The renowned traders sold musk, silver goods, silk, and slaves. Sogdian city-states, such as Samarkand and Bukhara, were cosmopolitan urban centers of culture but were never very powerful.

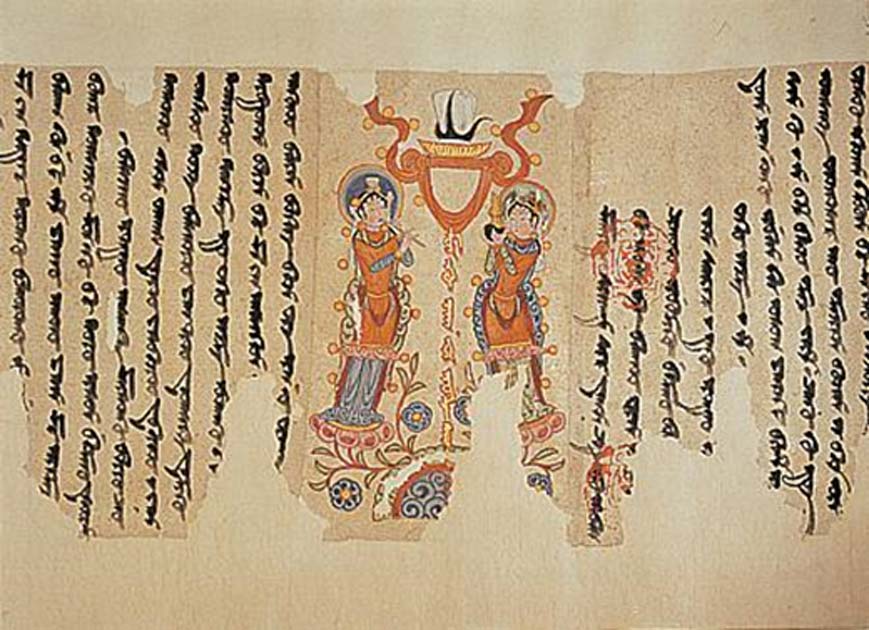

Top image: Sogdian text. Manichaean Letter (public domain)

Sources:

Sims-Williams, Nicholas. "Ancient Letters." Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica, 3 Aug. 2011. Web. 23 Oct. 2016. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ancient-letters.

Livshits, Vladimir. "The Sogdian "Ancient Letters" (I, III)." Iran & the Caucasus 12.2 (2008): 289-93. Web.

"The Sogdian Ancient Letters." Sogdian Ancient Letters. Trans. Nicholas Sims-Williams. School of Oriental and African Studies University of London, 2004. Web. 23 Oct. 2016. http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/sogdlet.html.

Vaissière, Étienne De La. "Sogdians in China: A Short History and Some New Discoveries." The Silkroad. The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter, 2003. Web. 23 Oct. 2016. http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/december/new_discoveries.htm.