The Heliand: A Germanic Account of Jesus Written to Suit the Saxon World

One thing that can be said about the history of Christianity is that it has always been multicultural and multi-ethnic. Christianity is not tied to any one ethnic group or cultural tradition but has been able to accommodate many cultures across time and space. One example of this is the Heliand poem which provides a Germanic expression of the life of Jesus by changing the cultural and linguistic setting of the story to the world of the Saxons.

Origin of the Poem

It is not known who the author was, but it is believed that the poem was written during the reign of the Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious sometime in the middle of the 9th century, possibly around the year 830 AD. The identity of the author is uncertain. Some scholars argue that it was a priest based on clear knowledge of the Christian theological tradition of the time, though some argue that it might have been a Saxon bard who had received a Christian education. This is based on the author’s skill in Old Saxon poetry.

The poem is believed to have been commissioned by Emperor Louis the Pious to make Christianity more understandable to some of his Germanic subjects. The Saxons had only been recently converted to Christianity against their will by Charlemagne and many of them had never been sufficiently instructed in the central tenets of their new religion.

Louis the Pious, contemporary depiction from 826 AD as a soldier of Christ. (Lestath / Public Domain)

Furthermore, Germanic cultural values such as their strong warrior ethos did not mesh well with Christian values or approaches to teaching. This made educating Saxons about the Gospel more difficult. This poem may have been written to remedy that so that they could be integrated into the growing civilization that was Christendom.

The earliest mention of the poem, after it was made, was by a 16th century Renaissance era scholar named Matthias Flacius Illyricus. Fragments of the poem were rediscovered around 1587 by another scholar named Junius who discovered a copy of the poem in the archives of the Cottonian Library. Parts of the poem were published in 1705 by John Hicks. The first full text of the poem was published in 1830. After this, it generated great interest not only for its religious and cultural significance for depicting Germanic Christianity but also because it is one of the only surviving major literary works written in Old Saxon.

- Worship? Meditation? Sacrifice? What Ancient Ritual Activities Were Held at the Externsteine Sacred Stone Formation?

- A Literary Treasure: The Oldest Surviving English Poem - Beowulf and His Epic Battles

- Transcription of ancient manuscript suggests Jesus married Mary Magdalene and had two children

Matthias Flacius Illyricus made the earliest mention of the poem in the 16 th century. (Tomisti / Public Domain)

Content of the Poem – A Germanized Gospel

To adapt the story of Jesus to Saxon culture, some details of the story are changed in the poem. Jesus is depicted more as a wise chieftain than a religious leader or divine teacher. He rules as a benevolent Germanic lord and prince of peace. The apostles are depicted as his loyal vassals or thanes who fight out of honor to protect their lord from his betrayers.

Furthermore, the Wedding of Cana takes place in a Germanic banquet hall with tables and benches and the host of the feast is a chieftain. Details about Jesus’ birth and temptation are different as well. The shepherds to whom Jesus’ birth was announced become grooms watching over horses instead of sheep. The wisemen have to travel through a forest to find Jesus. Jesus is tempted deep in the remote woodlands of Germany instead of a Palestinian desert.

The Wedding at Cana. (The Carouselambra Kid / CC BY-SA 2.0)

One pattern that is interesting about the poem is that in spite of the changes to make the story more Germanic, the basic message is the same. Jesus is presented as the true Saxon savior who is greater than all the ancient gods such as Thor and Woden. A comparison can be drawn with the German word 'heiland' meaning savior, with the poems’ title Heliand.

Saxons trying to learn about how to practice their Christian faith would have been unfamiliar with the idea of an itinerant preacher traveling the countryside from village to village with his disciples giving sermons about morality and theology. The idea of Jesus as the mightiest chieftain who was able to gain the allegiance of his thanes, rule with benevolence and peace, and give his life to save the world would have been easier for the Saxons to understand.

Legacy

The Heliand poem has interested many scholars because of the way it contextualizes Christianity for Germanic culture. This has led to interest in how other cultures have done the same. Because of the predominance of Christian Europe for most of the early modern period, Christianity tends to be associated with Western civilization. Christianity, however, did not start out as a Western religion. Christianity was founded in the Middle East by a Palestinian Jew and his disciples. In the 9th century, the Saxons, a Germanic people, were able to make a Middle Eastern religion that was adopted by the Romans their own through poetry.

This is an excerpt, from Fragment P, of the Heliand from the German Historical Museum. (Marielecourtois / Public Domain)

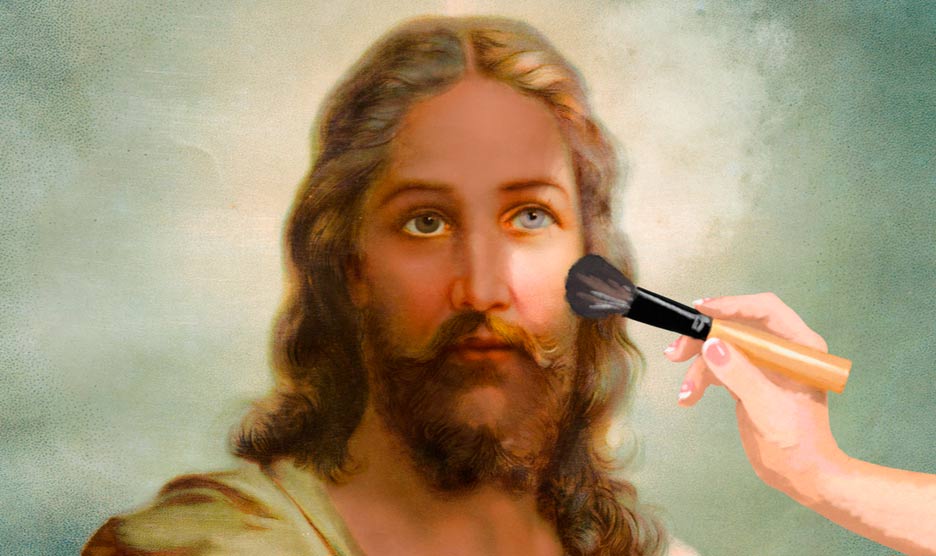

Top image: In the Heliand, Jesus wasn’t a dark-skinned Palestinian but a Germanic chieftain. Hans Zatzka (Public Domain)/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

By Caleb Strom

References

Herbermann. 1910. The Heliand. The Catholic Encyclopedia. [Online] Available at: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07205b.htm

Irvin, Dale. 1999. Where Would Civilization Be Without Christianity? The Gift of Mission. Christianity Today. [Online] Available at: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/1999/december6/9te058.html

Philip, R. 1947. A Ninth Century Life of Christ: The Old Saxon Hêliand. The Expository Times. [Online] Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/001452464705800906