Curious and Unusual Spells from the Greek Magical Papyri

The Greek magical papyri, as it is commonly known, is an extensive collection of ancient Greco-Roman Egypt magical spells, rituals, remedies, hymns, and myth. Scholars have placed its origin between the second and fifth century BC during Roman occupation. The papyri, a great deal of which was first acquired by a diplomat who went by the name of Jean d’Anastasi sometime in the very early 19th century, was predominantly sourced from a single collector out of Thebes. Due to the suppression and destruction of pagan texts brought on by Christianity, it wasn’t until much later that the papyri were to be examined, and over the course of more than a century thereafter to be fully translated.

The contents of this extraordinary collection are a unique combination of Egyptian Demotic and Greek text, with a heavy Hellenistic influence. Further, there is some late Egyptian Coptic text, hints of Babylonian, along with an early form of Judaism. The diversity in texts indicates several centuries worth of accumulated magic, written by a variety of magical practitioners. Among its pages are a plethora of love spells, divination spells, protection spells, victory charms, invocations of the gods, revenge spells, and so much more.

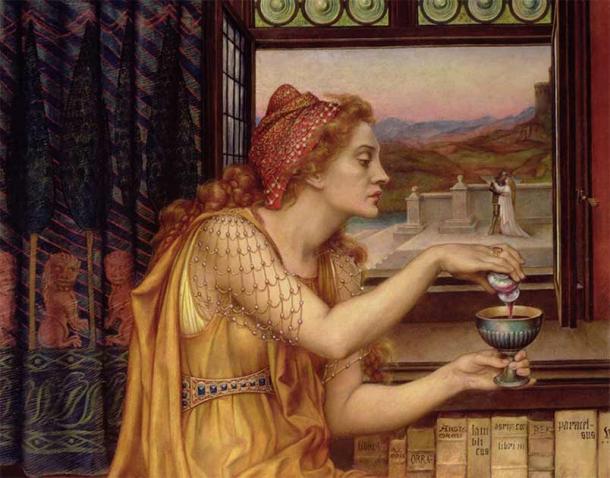

The Greek Magical Papyri is an incredible source of texts for learning about Greco-Roman Egypt magical spells, rituals, remedies, hymns, myths, and love potions. The Love Potion, by Evelyn De Morgan. (Public domain)

Evidence of Cultural Transmission into Egypt in the Greek Magical Papyri

When the Greeks made their way into Egypt in 332 BC and later the Romans in 30 BC, they brought with them many of their cultural traditions, aesthetics, and religious beliefs. However, they did not completely change the cultural landscape of Egypt. For instance, Alexander of Macedonia, the first Greek Pharaoh, restored many of the temples that were affected by the previous Persian invasion, and erected new monuments in honor of Egyptian gods.

- Magic in Ancient Greece: Necromancy, Curses, Love Spells, and Oracles

- Newly Translated Egyptian Papyrus Reveals Evil Spells of Coercion, Love Incantations and Healing Recipes

The gods and traditions of Egypt were respected and embraced by the new foreign leaders. Although elements of the Greek magical papyri texts contain Greek deities and Hellenistic influence, the intermingling of these different cultures created a distinct weaving of traits special to its time and place.

Alexander the Great, the first Greek Pharaoh, ensured a certain degree of respect for Egyptian culture after the Greeks took over. (Tony Baggett / Adobe Stock)

The Role of Magic in Ancient Egypt

Magic in ancient Egypt was profoundly established within its society. From religious rituals, interacting with the invisible forces of the world, connecting with the divine, to everyday and medical uses. Magic did not fall short of necessity for the Egyptian people. The term Heka was often used to describe this invisible and powerful force, and there were many ways in which a person could harness its power. One could call upon the gods associated with what was needed, either through connection using mythological precedent or through threats using persuasion.

The Egyptians practiced homeopathic forms of treatment, using things that were representative of the healthy opposite of an ailment, “like with like.” Additionally, it was believed to be contagious through touching an object with known Heka, such as a religious idol or stela. Magic was protective, productive, destructive, and potentially curative.

During its occupation, Greco-Roman magic was integrated into the traditional qualities of Egyptian Heka. The gods and goddesses of the Greek world were connected to their Egyptian counterparts. Ritual and magic could be done using either pantheon, or even a combination of sorts. One rather compelling adaptation found within the magical papyri is that the Greek deities took on a more folklore characteristic. They became dangerous and invoked fear, as opposed to the aristocratic nature once portrayed.

Spells to protect one from a daimon, a supernatural power or god, or to release one from its grips are consistently found within the texts. It is not all unfavorable with the gods, however, as a considerable number of spells are to utilize their more beneficial aspects, such as with a dream oracle spell, love or victory charm.

Apart from physicians, magical practitioners would have been educated members of the temple priesthood, well versed in the various religions that accompanied the region. They would have been called upon by people to provide the needed tools and assurance that what was desired would come into being.

The everyday person could present offerings, have a household shrine, participate in public rituals, among other common magical practices. Still, they could not perform the most specific of spells on their own as they needed guidance and specialized knowledge. In this way, the priests were essentially the gatekeepers of magical and religious knowledge; they kept record of their spells, adding to those who had done so before them.

It is no surprise that the ancients performed spells to protect, smite enemies, find love, and foresee uncertain futures. What may be a bit surprising is those spells that seem to serve an alternative purpose. As the priests recorded spells that were needed or asked for, anything could be within the realm of possibility. Consequently, and with hundreds of recorded texts, a few peculiar spells stand out.

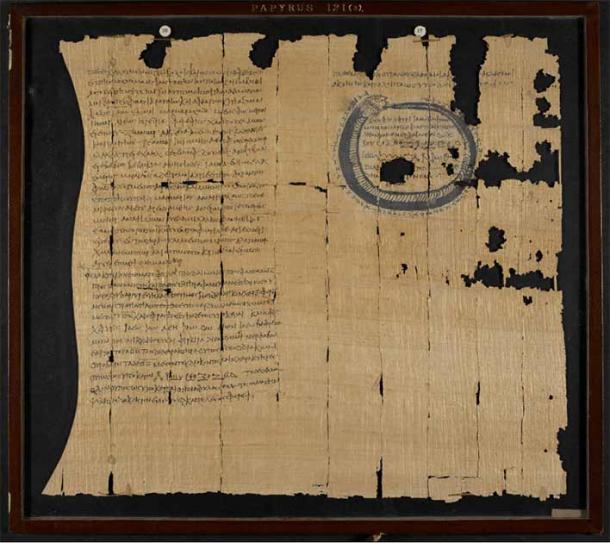

Papyrus 121 from the Greek magical papyri collection, which includes a variety of texts from a spells to keep insects out of the house, to charms to induce insomnia, and even an excellent for silencing others. (British Library)

Invisibility Spells in the Greek Magical Papyri

From modern day entertainment to the curious minds of people, the ability to be invisible can be rather intriguing. Apparently, the ancients thought so as well, as can be seen from the following invisibility spell within the Greek magical papyri.

“Tested spell for invisibility: A great work. Take the eye of an ape that has died a violent death and plant of peony(rose). Rub these with oil of lily.” (PGM 1. 247-62)

The spell continues with instruction to “rub from right to left” while reciting a spell to Anubis and Osiris to grant the gift of invisibility:

“And if you wish to become invisible, rub your face with the concoction, and you will be invisible for as long as you wish. And if you wish to be visible again, move from west to east... and you will be obvious and visible to all/men.” (PGM 1. 247-62)

From the title, it is clear that this spell had been tested and proven to be effective, or at the very least claimed to be. The spell does not provide any further details; so, it may be up to the reader’s imagination as to how this might have gone. Was the person to be nude? How exactly was it tested and proven? Someone wanted this spell and more likely than not went through with it. Did they become invisible? Probably not, but an entertaining thought nonetheless. This invisibility spell was not the only one, there are a few here and there scattered about the Greek magical papyri.

“Taking the egg of a falcon, gild half of it and smear the other half with cinnabar. Wearing this and you will be invisible when you say the Name.” (PGM XIII. 235)

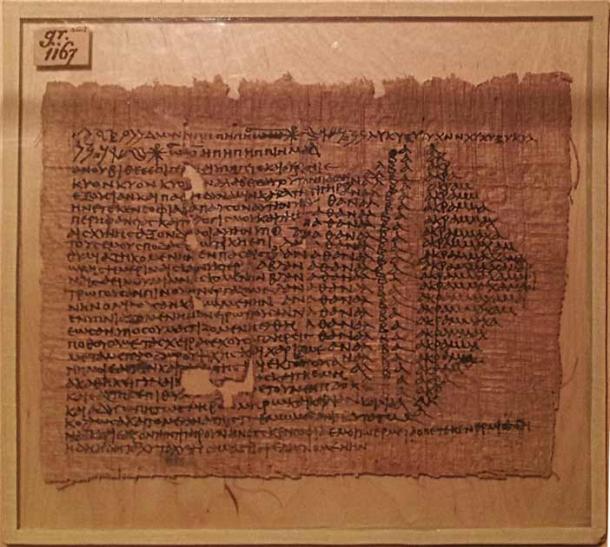

Greek magical papyrus with a love spell of attraction, addressed to the dog-headed god Anubis. (Public domain)

Greek Magical Papyri Spell for Crossing the Nile

“Egypt is the gift of the Nile”; words once spoken by the great ancient historian, Herodotus. In addition to the fertile lands produced by annual flooding (inundation), the relatively reliable transportation of the Nile was the perfect recipe for a thriving society. Though, in the event that someone wished to cross the Nile, but lacked a boat or other floatation device, what was there to be done? Coincidentally, there was a spell precisely for that.

“If you want to cross the [the Nile] on a crocodile: Sit down and say, ‘Hear me, you who live your life in the water. I am one who is at leisure in heaven and goes about in water and in fire and in air / and earth. Return the favor done you on the day when I created you and you made your request to me. You will take me [to] the other side, for I am so-and-so.’ Say the Name.” (PGM XIII. 285)

It is unclear to whether the individual attempting to cross on a crocodile was to sit on the river banks and summon a crocodile, or sit upon the crocodile’s back while reciting the words. Did they survive this dangerous feat and successfully cross the Nile this way? If so, that would have been quite the sight. Who would want such a spell or to why it was written as a magical means of transportation will remain a conundrum. Regardless, it is safe to say that you shouldn’t try it at home.

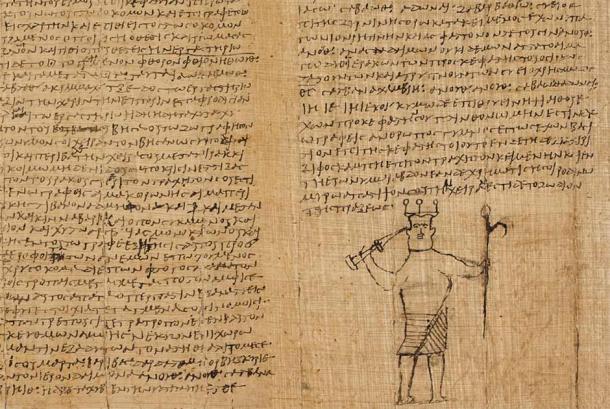

Detail from one of the Greek magical papyri in the British Museum, which includes a spell to grant prosperity and victory and another requesting a visit from a dream oracle. (British Library)

Attaining Immortality within the Greek Magical Papyri

To be one with the gods, immortal, to behold the wonders of the universe. It sounds rather far-fetched, but according to the Greek magical papyri, it is within the realm of possibility, if done correctly. Written for an only child, the magical practitioner claimed it to be “mysteries handed down [not] for gain but for instruction.” The spell is an invocation to the goddesses Psyche and Tyche. It asks for immortality, to “ascend into the heavens as an inquirer.” An extremely long spell with many prayers begins with a recitation, then continues:

“Draw a breath from the rays, drawing up 3 times as much as you can, and you will see yourself being lifted up and / ascending to the height, so that you seem to be in midair. You will hear nothing of either of man or of any other living thing, nor in that hour will you see anything of mortal affairs on earth, but rather you will see all immortal things.” (PGM IV. 475-829)

At this point, the inquirer must interact with different gods and goddesses, very careful and precise in greetings and prayer, traversing the places that make up the immortal world. It is full of instructions to please the gods, beginning with the powerful Helios and the seven fates of heaven.

Near the end of the journey, a deep revelation is revealed, and the newly immortal one is told that they can now initiate another if they are deemed worthy. The spell continues with the initiation process for another, including an ointment for immortality made of lotus, honey, and rose oil. Quite a fantastical adventure all in all, and one that deviates from the idea that only gods may possess the gift of immortality.

Frivolous Spells in the Greek Magical Papyri

Not all things contained in the magical papyri are for serious matters, there are a few frivolous spells that would have made a social event a bit more interesting and are deserving of mention:

“To make men who have been drinking at the symposium appear to have donkey snouts to outsiders, from afar: In the dark [take] a wick from a lamp and dip it in donkey’s blood; make a new lamp / with the new wick and touch the drinkers.” (PGM XIb. 1-5)

“To make one bend down and not get up: Anoint the loins with the brain of an electric eel.”

“To cause a fight at the banquet: Throw a dog-bitten stone into the middle.”

“To make wine sour: Throw burning / pebbles into it.”

(PGM CXXVII. 1-12)

The Rhyme and Reason of Magic

For the ancients, magic was an integral part of life and community. The charms, spells, rituals, and stories brought meaning and purpose to an otherwise chaotic world full of uncertainty and conflict. Why did so many ancient, and still modern, societies practice magic? Simply put, magic provides a sense of control over an uncontrollable world. Anthropologists who study the works of magic over time consider it a phenomenon that stems from the human tendency to want to have control over the outcome of situations.

For those who practice, if the spell works, then it was done correctly. If it fails, then it is not a fault in the concept itself, but a fault of the ones performing the spell. Thus, there can always be a reason to believe in the magic even if it does not give the desired outcome.

- Ancient Egyptian Sex Spell Invoked a Ghost to Entrap a Man

- Unleashing The Power of the Gods: Hexes and Black Magic in the Ancient Greek Olympics

Hans Dieter Betz (1992), who compiled the various translations of the Greek magical papyri into English and from which these spells discussed are drawn from, had a slightly different perspective. He considered magic in this context to be an elaborate scam:

“Magicians are those who have long ago explored these dimensions of the human mind. Rather than decrying the facts, they have exploited them. Magicians have known all along that people’s religious need and expectations provide the greatest opportunity for the most effective of all deceptions.” (Betz, p. xlviii)

Yet, there is still another perspective, one of openness and curiosity. People all over the world currently practice magic and express a deep unwavering belief in its efficacy. Is it justifiable to dismiss centuries of practicing magic workers because it lacks concrete scientific evidence? Not everything in this world can be easily explained, and that is part of the adventure of the human experience.

Spells written thousands of years ago are comparably the same spells people utilize today. One of the most common spells found in the Greek magical papyri are those related to love; much the same can be said about the spells of today. Magic does not necessarily need proving, it only needs belief. With such an abundance of works throughout time, whatever curious and unusual thing one may require, there is probably a spell out there just for that.

Top image: Selection of Greek Magical Papyri which are kept at the British Library. Source: British Library

By Jessica Nadeau

References

Betz, Hans Dieter. 1992. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation: Including the Demotic Spells. Second Edition. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, IL & London, UK.

Comments

Magic and religion both require belief. Not found in the animal kingdom, but is based in human consciousness. This is the final frontier. Apparently the ancients were as intrigued by this as we are today. From dream interpretation to controlling others. Have we really progressed? I'll leave that to you to decide for your self. I think not.

I tried crossing the Nile on a crocodile but I got eaten

but I got better.