Neolithic Stone Balls: The Northern Rosetta Stone?

Neolithic stone balls are mysterious petrospheres found in Scotland, Ireland, and Norway that have puzzled archaeologists for centuries. But an explanation for these objects may finally be revealed, showing their potential links to the first astronomical clocks and the development of modern timekeeping.

Crichton E M Miller is an author, researcher, and Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport who patented and published the pre-Christian wheel or sun cross as a spherical inclinometer for navigation, surveying, and astronomy in the Bronze Age using the Neolithic stone balls as a plumb bob in his book, The Golden Thread of Time.

While researching navigation methods during the Bronze Age, Miller recently carried out experiments at the autumn equinox on Scotland’s West coast in 2022, using models of the mysterious stone balls found in Scotland, Ireland, and Norway.

- Could the Strange Prehistoric Carved Stone Balls Represent Atoms?

- Six Ancient Stone Spheres from Diquís Delta in Costa Rica Excavated

Astronomical Clocks

Time was once kept by observing the stars, sun, and moon, leading to the invention of the first astronomical clock at Padua, Italy in the 14th Century. This clock resulted from measuring the motions of the earth, sun, and moon against the twelve signs of the zodiac. The sun’s position became the hour hand in a different zodiac sign as the year progressed, the moon’s phases are shown, and the earth is represented by a ball. In the 18th Century, the innovation would lead to Harrisons H4 watch for finding longitude at sea.

First astronomical clock built at Padua, Italy in 1344 AD. (Pxfuel)

A zodiac sign is invisible in daylight but was calculated by the opposite star sign seen due south at midnight, which is why zodiacs are shown as measured circles.

The construction of the first twenty-four-hour clock may help in explaining the hundreds of highly decorated and partially carved ancient stone balls mostly found in Scotland, when seen as spherical sundials.

Spherical Sun Dials

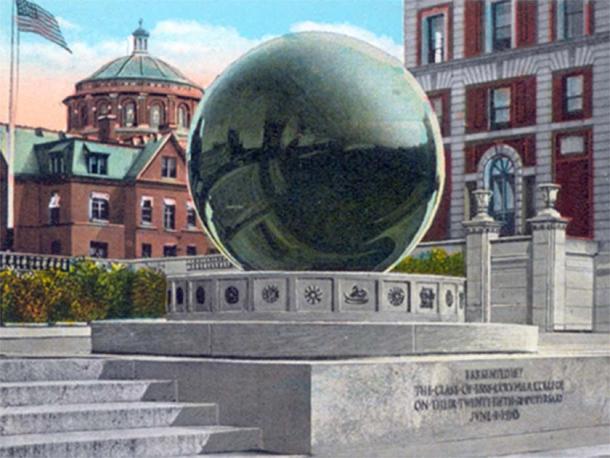

The semi polished stone balls can cast reflections and shadows in the same way as modern polished spherical sundials.

Spherical sundial that originally stood at the center of the Columbia University campus. (Public domain)

The stone balls are called petrospheres, and they are all nearly the same size and weight. Most are found in Aberdeenshire and the finest one of all was found within a few hundred meters of the river Don and called the Towie Ball, after its geographic place of discovery.

Carved stone ball from Towie in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Sir John Evans. ‘The Ancient Stone implements, Weapons & Ornaments of Great Britain.’ Longmans, Green & Co. 1897. P. 421. (Public domain)

The Towie Ball is covered in fine markings that nobody has deciphered so far, some think it is unfinished because the bottom is blank. Carved from granite and about 7 centimeters (2.76 inches) in diameter, archaeologists determine that there are over four hundred stone balls found of the same size and weight and that they were designed to be portable; the author agrees with this assessment and considers that these balls could have acted as the equivalent to modern wrist watches, keeping time on the move.

Neolithic carved stone balls, Scotland by National Museums Scotland on Sketchfab

Bronze Age Seafaring Trade Routes

Long distance trade during the Bronze Age Entanglement is similar to today, in which goods travelled by sea from Scandinavia, Britain, and Ireland to the Mediterranean and back, for tin and copper and soapstone, which was used for the casting molds which came from Norwegian quarries and the Shetland Islands until the trade collapsed around 1200 BC, which is known as the Bronze Age Collapse.

Trade routes vanished and countries shrank into smaller isolated states with Scandinavia remaining apart until the Roman Empire declined and the Viking Age began using ancient knowledge on navigation and time keeping and re-opened the Mediterranean trade routes.

Viking Sun Stones

Many think that the Feldspar crystals of Iceland made the original Viking Sun Stone, but Iceland was not discovered for millennia after the stone balls were manufactured and the crystal was never discovered with ships until the medieval period.

Shipping cargo abroad requires navigation, which means keeping time. Since there were no clocks, time had to be calibrated by observing the sun and the moon and their positions related to the ecliptic plane. This is where cup and ring marks come into the equation.

Cup and Ring Marks

Cup and ring marks are found carved in rocks in many places quite close to the coasts and rivers in Scotland, Ireland, England, France, and Spain. They are currently thought of as prehistoric art; but perhaps that definition is in error, they seemed to be far more practical than that.

It seems obvious that the ball is meant to sit in the cup. The balls and cups are the same size and fit together. That would also explain why the bottom of the Towie Ball is blank, rather than unfinished, because when it’s in the cup you can’t see the bottom of the ball, but you can see the sides and top.

Cup and ring petroglyph at the 'Laxe das Rodas' ('Stone of the Wheels'), Louro, Galicia. (Froaringus / CC BY-SA 3.0)

The cup at the 'Laxe das Rodas' shows a shadow from the sun to the left-hand side, so what might happen if the rings were filled with water or oil? The answer is obvious - they would be reflective! On sunny days the rings would reflect the sun and at night the moonlight would be reflected, just like reflections at sea.

Field work occurred at the ancient petroglyph site at Achnabreck, Lochgilphead, Argyll and Bute, Scotland 56⁰03’04” N and 5⁰26’34” W, at an elevation of 77 meters (252.63 ft.)

- Was This Giant Stone Sphere Crafted by an Advanced Civilization of the Past or the Forces of Nature?

- Mystery Solved! Strange Stone Spheres are for an Ancient Greek Board Game!

A Ball in the Ring

The author took a model ball out of his pocket and placed it into the cup at Achnabreck to begin the experiment.

Author placing a stone ball in a cup and ring mark in Scotland at the autumn equinox in 2022. (Author provided)

Made to the original size, the ball fits the cup perfectly and the whole thing becomes a model of the earth and the solar system, with the sun slowly moving as the earth turns.

Applying Fluid

Now if we look carefully we see that the grooves, the channel run off, and the cup are obviously designed to hold liquid.

Anointing the stone ball with water at the same time as filling the circular grooves surrounding the cup and the petrosphere. (Author provided)

In the image below, we see an impression of a petrosphere found in the Orkneys which has a grid scratched on its face.

Petrosphere from Skara Brae, Orkney showing east to west graduations grid with solar highlight. (Author provided)

Wetting the ball shows a high-definition highlight in the grid with the position of the sun or moon when aligned to true south, possibly explaining the purpose of the grid scratched on its surface. The highlight on the grid shows the latitude of the sun to the east of the observer’s position at solar noon, as described by an analemma at the autumn equinox.

However, the Towie Ball is far more sophisticated and could be showing analemmas carved on its surface along with the seasons, showing latitude as well as time and date.

Analemmas

Solar time based on an analemma during the autumn equinox noon in civil time shows the sun’s position is to the east of south in the experiment.

The designs of the Towie Ball are far more complex, and the designs seem to copy the analemma created by the sun in its daily position in the sky when cast as a highlight on the ball facing south and a shadow extending to the north on the rings.

We see what looks like analemmas in the earthworks at the Hill of Tara, Co Meath, Ireland near the river Boyne and in the carvings at Newgrange on the same river a few miles downstream.

Photo from circa 1900-1910 of analemmas at Newgrange, Co Meath, Ireland. (The Commons)

Hill of Tara with an analemma oriented to the winter solstice. (Google Maps)

Positions of the sun related to a Great Circle meridian throughout the year. (Public domain)

Observing the Towie Ball, we see that the designs include the shape of solar analemmas as a figure eight, where analemmas which can be determined by monoliths placed in the ground and measured at the same time every day, week, or month, as in the following research.

Ship Burials and Analemmas

In Sweden we find analemma shapes overlooked by observation mounds to the southwest, indicating summer and winter solstice directions which are quite clear in the so-called “boat” burial mounds.

Two of the Viking stone ships (burial grounds) at Badelunda, near Västerås, Sweden. (Berig / CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are fifty-two stones in the analemma shape, which mark the 52 weeks of the year positions of the shadows created by the analemma. There is an obvious connection with ships and navigation since it is situated only three miles (4.83 km) from Lake Vasteras, which leads to the Baltic Sea and on to the North Sea and Atlantic.

- Geometric Stone Spheres of Scotland: Part 1 – More Than A Projectile - What Possible Purpose 5,000-years Ago?

- Geometric Stone Spheres of Scotland: Part 2 – Explanations From Platonic Solids to Sexual Healing

At 59.6308° N latitude, the setting sun lowers in the sky approaching the winter, extending the evening shadows toward the north-eastern section. The curved shadow of the sun cast by the southwestern mound in the image above extends to the north-eastern circle before shortening and returning towards the spring equinox shown at the junction, before proceeding to the summer solstice and completing the annual cycle.

These burial mounds and stone circles are dated much later by archaeology, to around 1000 BC.

Anundshög, Sweden. (Google Maps)

Lunar Observations

The system used for reflecting the sun and casting a shadow also works for the moon, which casts a sharp reflection when it is in view in the night sky.

Moon reflection and shadow at night to the east of south. (Author provided)

In the case of the moon, crossing the ecliptic plane 5⁰ above and 5 ⁰ below centered as lunar nodes.

Neolithic moon dial example viewed to the south at midnight at separate times of the year. (Author provided) This shows the Moon at its lowest and highest altitude transiting both a meridian and ecliptic plane, the moon shadow to the north of the nodes can be calculated in a lunar calendar.

Bringing it All Together

Petrospheres and cup and ring marks can create a lunisolar calendar as well as a tidal calendar. Modelling, experimentation, and field trials prove that the petrospheres combined with the cup and ring marks work as a lunisolar clock and calendar, but whether they did or didn’t in the past is open to debate.

Top Image: Neolithic stone balls in the British Museum. Source: British Museum / CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

By Crichton E M Miller FCILT

References

Atlas Obscura (2018) ‘Padua Astronomical Clock.’ Atlas Obscura. Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/padua-astronomical-clock

British Museum (n.d.) ‘Stone balls from Skara Brae.’ Teaching History with 100 Objects – The British Museum. Available at: http://teachinghistory100.org/objects/for_the_classroom/carved_stone_ball_from_skara_brae

Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport (n.d.) ‘About Us.’ Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport. Available at: https://ciltuk.org.uk/About-Us

Grenne, T. et al. (2017) ‘Soapstone in the North: Quarries, Products and People. 7000 BC – AD 1700. UBAS University of Bergen Archaeological Series, edited by Gitte Hansen and Per Storemyr.’ Academia.edu. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/34711048/Soapstone_in_the_North_Quarries_Products_and_People_7000_BC_AD_1700_UBAS_University_of_Bergen_Archaeological_Series_edited_by_Gitte_Hansen_and_Per_Storemyr

Miller, Crichton E M (2000) ‘Patent GB2344887 on the Solar Cross as a spherical geometrical measuring instrument ancestor of the astrolabe, theodolite and the sextant displayed in pre Christian Neolithic and Bronze Ages glyphs for primitive astronomy permitting sea faring astro navigation and megalithic alignments.’ Academia.edu. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/18140557/Patent_GB2344887_on_the_Solar_Cross_as_a_spherical_geometrical_measuring_instrument_ancestor_of_the_astrolabe_theodolite_and_the_sextant_displayed_in_pre_Christian_Neolithic_and_Bronze_Ages_glyphs_for_primitive_astronomy_permitting_sea_faring_astro_navigation_and_megalithic_alignments

Miller, Crichton E M (2014) The Golden Thread of Time: A Quest for the Truth and Hidden Knowledge of the Ancients. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Golden-Thread-Time-Knowledge-Ancients-dp-

National Museums Scotland (n.d.) ‘Towie ball.’ National Museums Scotland. Available at: https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/scottish-history-and-archaeology/towie-ball/

Royal Museums Greenwich (n.d.) ‘H4.’ Royal Museums Greenwich. Available at: https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-79142

Comments

It’s obvious to me, at least, that they are massage balls. You can get some new ones that look just like that, the Asians know. The question is, how ancient are they? Once made, they last forever.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.