Gammel Estrup Manor: Alchemy, Astronomy, and Secret Symbolism Revealed

Usually we notice architecture when it is a visible expression of beautiful forms. But architecture can be symbolic too. The Danish 16th century manor house called Gammel Estrup reveals a symbolism that is often overlooked today. Based on the sciences of that time, alchemy and the dawning of astronomy, the building is a northern Renaissance gem.

Gammel Estrup (Yves Wohlers /Adobe Stock)

Geometry can be fascinating and has even been regarded as sacred. Already at the entrance to the castle it is clear that geometry was important here. The Golden Spiral determines the placement of both the gate and the windows above the gate from the symmetrical axis of the gate tower. You may have seen more complicated Golden Section drawings on Italian Renaissance buildings. This version looks simpler, yet this castle also reveals several other aspects of long forgotten symbolic craftsmanship.

The Architect Behind Gammel Estrup

Around 1617 the entry gate was moved to the current wing, when the castle was rebuilt from a smaller medieval closed fortress to this three-winged demonstration of wealth. Today Gammel Estrup is a manor museum and the buildings surrounding it a farming museum. In 1617 the estate was owned by Eske Brock (1560-1625), a member of the king’s council and good friend of King Christian IV. Surviving notebooks tell us that Eske Brock bought many building materials that year. We also know the name of his architect: Mathias ‘Bygmester’ (master builder).

- Competing for the Title of the Oldest House in England - Luddesdown Court and Saltford Manor

- Puzzling Stone Age Labyrinth Discovered in Denmark, What Was It Used For?

View from east. The southern wing (left) was new. The gables were curved in Dutch style except for the gate tower, which curiously was provided with stepped gables instead. Later all gables were made into stepped gables. (Author provided)

Sacred Geometry at the Manor House

The Renaissance was delayed in northern Europe, but Gammel Estrup’s style didn’t incorporate classical columns. Instead it mirrored the Renaissance’s dawning science, especially astronomy. Perhaps this was because Eske Brock’s daughter was married to a nephew of the world-renowned astronomer Tycho Brahe. Tycho Brahe had died in 1601.

As demonstrated on the photo above, the Golden Spiral determines the asymmetry of the gate tower. The Golden Spiral is constructed by drawing a quarter of a circle into a quadratic square, and enlarging its side length in the Golden Section proportion, adding bigger and bigger squares.

Drawings of Golden Spiral squares are also applied horizontally to a hall on the ground floor of the ‘new’ southern wing. Again the entrance (from the staircase tower) is situated at the small end of the spiral.

Features in the Chapel

The chapel is adjoined to this. Its length is determined by turning the diagonal of a quadratic square with a pair of compasses to be used as a new side. This is one of the formats which the Italian architect Andrea Palladio had named especially beautiful in his ‘ Quattri libri di architettura’ (1570). It is also very practical – so practical that we still use it to cut paper in the ‘A’ format. The special thing about this proportion is that when the paper is divided in the middle, the two sides maintain the ‘A’ proportion, and they can be divided over and over while maintaining it (A2, A3, A4, A5…).

Geometry is demonstrated in the ground floor of the ‘new’ southern wing of the castle. The Golden Section was used for the eastern end hall, and another proportion for the other end. This format is still used today in papers following the ‘A’ format (e.g. A4 paper). (Author provided (underlying drawing by architects Kjaer & Richter))

Confirming that these two formats are important, the exact same formats are accentuated in the fireplace in the chapel. Two friezes mark both the A format and the Golden Section.

The chapel’s fireplace with a double set of friezes marking the two proportions. (Author provided)

Heavenly Vaults

The chapel is quite strangely built, with brick vaults like the basement below. This ceiling type is curious here because the ceiling in the adjoining hall has a normal aspect and heavy beams. So why do they have these vaults in here?

The chapel with brick vaults and the fireplace to the left. The borderline between the circular higher half and the plain, straight lower half is clearly emphasized, having yin-yang-like opposite joints where columns meet vaults. (Author provided)

The room is composed of two horizontal halves. The lower half is normal, with squared angles and straight lines; it can be likened to a low box, whereas the upper half consists of round vertical forms. To draw squares, you need an orthogonal tool, and to draw circles a pair of compasses.

The Freemasons use these two instruments as the symbol of their fellowship and a reference to God as the Great Architect. The square with its straight lines, and the compasses’ circle symbolize earth and heaven. The old Masonic ideal is to unite the two – in people and in buildings. This unification is demonstrated in this chapel.

Masonic logo. (Public Domain)

Two low pillars in the middle support the vaults. Notice how the curved heavenly vaults meet in two squares supported by the two round pillars rising in the lower straight-lined ‘earth’ part of the chapel, like the yin-yang symbol, which likewise has contrasting points in the main figures. The accentuated joints demonstrate that here just beside you, at eye-level in this very chapel, heaven and earth meet. Today, very few, if any, of the visitors notice this symbolic curiosity.

The ground plan of the chapel, the A format, is adequately constructed using both – and only – squares and a pair of compasses.

This unusual ‘The Star’ Tarot card (JacquesViéville, c. 1650) shows how the pair of compasses is used by the wise man to incorporate drops of heavenly wisdom into the tower, symbolic probably for a person as well as for a building. (Author provided)

In a World of Alchemy

Around 1600 the world was still believed to be created by God in mixtures of the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. Alchemists also believed a fifth element existed: the quint-essence or ether, the finer essence of the four material elements. Much of their work in the laboratory was aimed at concentrating the finer elements and separating them from the lower substances – by dissolving, distilling, and desiccating (‘solve et coagula’). Distilled wine for example, gave fluid alcohol: strange ‘water’ which could burn because it contained more of the lighter fire element.

The alchemy tower. (Author provided)

The Alchemy Tower and the Elements

In one of the octagonal towers we find traces of an alchemical laboratory. Tradition names the grandson of Eske Brock ( Christen Skeel ‘the Rich,’ 1623-1688) as the one interested in alchemy, but when it was built the tower was already laid out to suit alchemical experimentation. Additionally, there was a direct connection through a door into the corner of the chapel, to assure that praying and contemplation (Christian meditation), which was an important a part of the work in serious experimenting, could take place in the best surroundings.

The Alchemy Tower’s Elements

The new Rosicrucian fraternity pleaded for a scientific reformation to follow the religious one. The flask drawing from 1617 by Robert Fludd, a wholehearted Rosicrucian, nicely explains the natural order of the elements in nature, based on their relative weights. This concept is widely forgotten today when referring to the elements, but it is an essential concept to understanding alchemy.

Robert Fludd’s drawing of the order of the elements in ‘Utriusque Cosmic Historia,’ 1617. (Author provided)

Gammel Estrup’s alchemy tower symbolically contains the elements in the same order. The basement chamber for earth, and the ground floor chamber containing the alchemical laboratory for water (because all substances must be dissolved to be distilled and thereby become airy, using fire).

Remnants of an alchemical laboratory with side oven for distillation and bars covering the windows. (Author provided)

Above these two is a chamber having the walls decorated all over with painted light blue drapey curtains, for air.

- Archaeologists are Ecstatic that a Major Viking Age Manor is Finally Found in Sweden

- Beautiful and Enigmatic Spirals of Golden Thread Uncovered in Denmark

Painted draped curtains in the blue chamber. (Author provided)

These three chambers were interconnected by a spiral staircase symbolic of the distillation process, but it would also be useful for gathering raw materials in the basement, completing practical experiments in the laboratory, and keeping records, writings and books in the blue chamber.

Nowadays the spiral staircase in the alchemy tower is only open in the basement and ends under the now closed floor of the blue chamber. The opening into the laboratory, and the laboratory’s opening to the chapel, have both been walled up some time later, maybe when the target changed to gold production. (Author provided)

The Significance of Urine

The tower had a shaft built on the back end containing (at that time) primitive toilets. In the basement chamber’s wall there is a narrow tunnel leading into the bottom of the shaft. A removable chute could function to tap urine off to use it in experiments. Perhaps the first alchemist here, Eske Brock, was more interested in isolating fertilizing substances (or a quint-essence life-enhancing concentrate) than in making gold.

Notice the small hole in the wall against the toilet shaft. What was the purpose of a straight horizontal tunnel into the toilet shaft? (Author provided)

In 1669 German alchemist Hennig Brand isolated phosphorus from boiled urine. He must have thought the shining substance was closer to the coveted “philosophers stone” essence than anything previously made.

Joseph Wright of Derby: ‘The Alchymist, in Search of the Philosopher’s stone, Discovers Phosphorus, and prays for the successful Conclusion of his operation, as was the custom of the Ancient Chymical Astrologers.’ 1771. (Public Domain)

Reaching the Observatory

Above the three directly-connected chambers in the tower was a fourth chamber only accessible from the top floor, this originally was the distinguished floor including the Knights Hall (which was later moved down one floor to its present location). This floor’s chamber in the tower would symbolize the fire element, but today nothing in here hints to alchemy.

Above this again, the top of the tower had a chamber which could not be accessed except through the attic, matching the distant cosmic ether element out of normal reach. From this chamber it is possible to enter the flat roof, where the rise of the planets could be observed in the eastern horizon above the trees.

The unusual flat towers could function as platforms for observation of the sky.

(Gammel Estrup – Herregaardsmuseet (the Manor Museum))

It is doubtful whether this was ever used practically, but flat roofs were unusual. Towers now had spires. The flat towers could be intended to look like symbolic medieval fortifications, but the railings on top resemble crowning symbols more than embrasures.

It is not at all unlikely that the purpose of the flat towers was to display pride in the family’s connection with the famous astronomer Tycho Brahe. 25 years later the king had a flat tower, Rundetårn (‘Round Tower’) built in the middle of Copenhagen as an observatory.

I have been told by a former leading curator at Gammel Estrup that Mathias Bygmester had his initials MB written into the cement on the top of the alchemy tower. It is no wonder this is the spot he wanted to sign. The towers are his masterpieces.

Renaissance Astronomy

In the chamber with the painted blue draped curtains, the ceiling is painted black and decorated with different flowers, spirals, and spires. In the middle is a painted rose, framed in a hexagon of golden wooden strips. Twelve other strips radiate from the inner hexagon to a larger one, from where six strips radiate to the round inner wall.

The decorated ceiling in the blue chamber. (Author provided)

The black ceiling with the flowers is probably a poetic description of the starry sky. The rose in the middle most likely depicts the sun, radiating its light.

Galileo Galilei developed a useful telescope in 1609. With it he observed many interesting details. It is possible that at Gammel Estrup they knew of Galilei’s astonishing observations, and a detail which nobody usually notices can be linked to one of them.

The inner hexagon of golden strips is slightly turned when compared to the outer, which causes the radiating golden strips to miss the center if elongated inwards. It could be due to a sloppy carpenter, but one of the things Galilei saw in his telescope and published in 1613 were sunspots – and he noticed that the sun turned with them. This ceiling may be a sophisticated statement, telling about one of the newest astronomical discoveries in a way only few would understand.

Depicting the Solar System

Placing the sun in the middle of a ceiling depicting the sky hardly alarms anybody today, but in the beginning of the 1600s the sun’s placement in the universe was a question of debate. Galileo Galilei supported the Heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus which placed the sun in the center and the planets, including the Earth, all orbiting the sun. The papal church maintained its stand that God had placed earth immobile in the middle of the universe.

The Heliocentric system was banned in 1616 – so it was a hot topic when Gammel Estrup was rebuilt, even though Denmark had turned to Protestantism. It is well-known that Galilei had to recant his views to avoid being burnt at the stake as a heretic.

Tycho Brahe had earlier proposed a compromise, in which the Earth was in the center and the sun and moon orbited the Earth, but all the planets orbited the sun. Actually it was quite clever because it follows Copernicus’ system except for the Earth and the sun and he couldn’t measure how the Earth moved compared to the stars because he didn’t realize just how far away the stars are. Important Catholics preferred his model.

Tycho believed in his own model. As an astrologer he may also have regarded the sun and the moon equally important and therefore possibly wished their orbits to balance, circling around Earth.

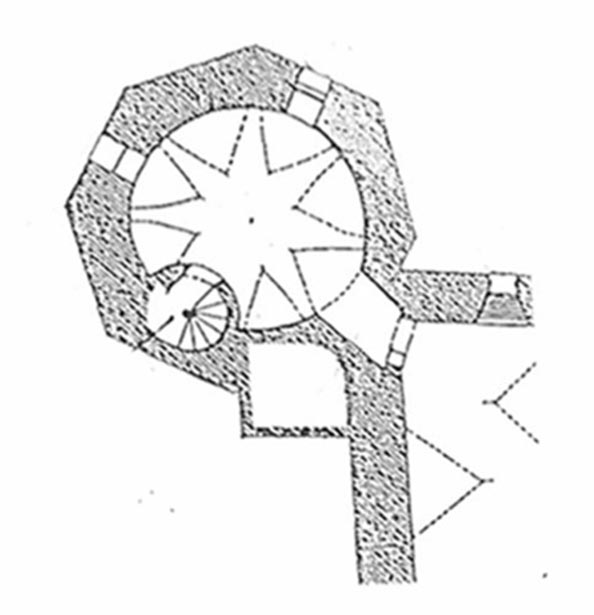

A ground plan drawing of the basement chamber of the tower displays its vaults as a star. The spiral staircase leading up to the laboratory looks like a planet orbiting the sun. Is this unintentional, or is it a built-in praise of the heliocentric system, even though it opposes the Tychonian system?

The alchemical tower’s basement plan with the Sun in the center and Earth orbiting it?

Drawing by architects Kjaer and Richter. (Author provided)

Elliptical Orbits

Tycho’s measurements of the stars and planets were the finest ever before the telescope. His many years' measurements of the planet Mars’ positions were used after his death by Johannes Kepler to calculate that planetary orbits weren’t perfect circles, but ellipses. Kepler’s laws of planetary movements were published in 1609.

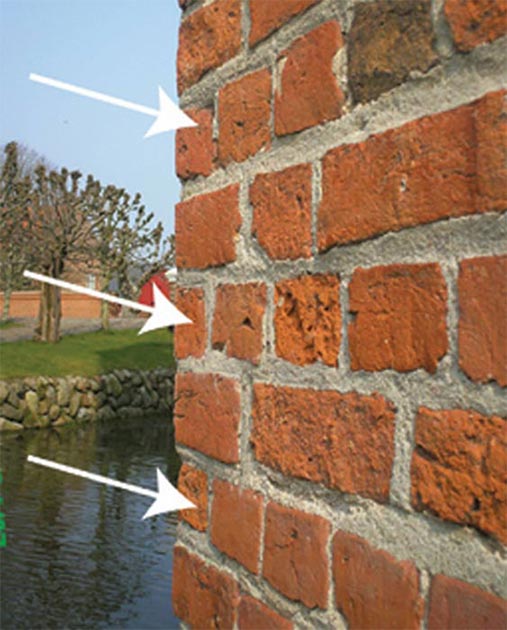

The flat octagon alchemy tower displays a curiosity in its corner angles, which makes the tower slightly oval. In a perfect octagon each angle is 135° (45° cut off at corners). I have measured the alchemy tower to have two opposite corners of 130° (50° cut). Two corners are non-existing: where the tower is connected to the main building.

Two opposite corners with slightly pointed angles. Lengths and angles are measured and drawn by author.

The two ‘wrong’ angles even apply to the granite foundation stones and continue up to the top. The most surprising was realizing that all corner bricks were fabricated with the 50° cut angle, even for the corners turning 45°. But it is easier to hide every second corner brick turning it a bit into the masonry than if they were sticking a bit out on the two 50° corners.

So two ‘sloppy faults’ (bricks and corners) may be intended to make the towers slightly oval, honouring Keplers discovery based on Tycho’s work. The inside walls of the octagonal tower are plastered oval. Centimeters from circles, but clearly measurable.

The bricks are all cut to fit a 50° turn, even at 45° corners, so every second brick on each side of these corners turns a bit into the masonry. (Author provided)

A Strange Turning of Towers /

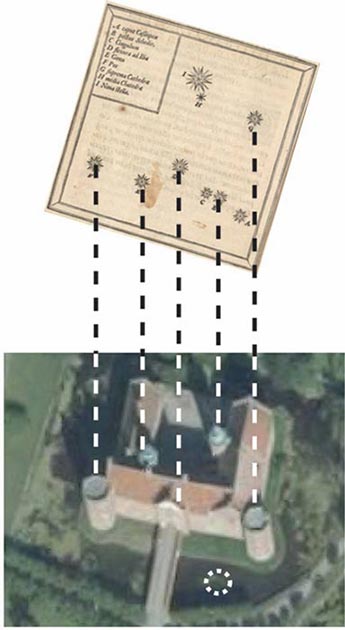

The two flat towers are symmetrically turned a little outwards from the center line, so they aren’t built perpendicular into the main building. Even the courtyard’s staircase-tower, which was moved in the rebuilding process, had been turned like the alchemy tower. I couldn’t figure out why, until I began to search for relations to Tycho Brahe’s greatest discovery, concerning a new star close to the constellation Cassiopeia.

Actually it was a supernova, an exploding star, but at that time the starry sky was believed to have been made perfect by God and eternally unchanging. Tycho calculated that the new star was beyond the moon’s sphere, which meant it was in the starry sky.

The towers are positioned as built under the constellation of Cassiopeia. The position of the new star is in the moat. Author provided with Tycho’s wood-cut and Google Earth photo underlying.

In his book ‘ De Nova Stella’ (1573) there is an illustration of Cassiopeia and the new star. If held above the head, Tycho’s wood-cut of the five ‘W’ stars of the constellation rather precisely matches the relative positions of Gammel Estrup’s towers. They can be said to be built under the stars – therefore mirrored, when you turn the book and put it back on the table.

This explains why the towers are turned: to hint at the slanting lines of Cassiopeia’s W.

- Has The “Red Bag” That Once Held Sir Walter Raleigh’s Decapitated Head Been Discovered At An Old Family Manor?

- Five Huge Bronze Age axes discovered in a field in Jutland, Denmark

Basement plan with the towers connected to show the close correspondence with Tycho’s mirrored wood-cut. The slightly slanting angles of the towers gives hints to Cassiopeia’s W. Author provided (architectural drawing by Kjaer and Richter).

The most surprising is the location of the new star. Following Tycho’s wood-cut, the star is over the moat. In real life a wellspring supplies the moat with fresh water almost exactly here. The wellspring can be located in wintertime, when ice covers most of the water’s surface.

New fresh water – new star. That’s sublime! How could we have almost forgotten such wonderful symbolic architecture?

Top Image: Photo and drawing of Gammel Estrup by the author. Source: Niels Bjerre

By Niels Bjerre

This article is an extract from the e-book “Bygget Alkymi” (Built Alchemy), which also gives introductions to different sides of alchemy. It can be downloaded for free (pdf) So, if you read Danish you can find it at:

http://www.hevringby.dk/E-forlag1.htm

If you wish to visit the Manor Museum, please see: http://gammelestrup.dk/en/