The Flavian Amphitheater that Bought Emperor Vespasian’s Popularity

Amphitheaters were a large part of the Roman culture and they were built in many of their cities across their empire, such as El Jem in Tunisia, Nimes Arena in France, and Leptis Magnus in Libya. They have fascinated people for centuries and today they are still popular with tourists. One of the best-preserved of the remaining amphitheaters is the Flavian Amphitheater in Pozzuoli, southern Italy. This 2000-year-old structure offers visitors an opportunity to experience a glimpse of the entertainment so loved during the Roman era.

Gladiators and blood. The history of Flavian Amphitheater in Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli was once a Greek colony that flourished for many centuries. It was captured by the Romans after the Second Punic War and became a Roman urban settlement known as Puteoli. Egyptian grain was imported though the bustling port and the city prospered from trade. The area was often threatened by Solfatara, now a dormant volcano that last erupted in 1198. It is believed that the ash and pumice from the volcano were used to make some of the first concrete.

During the First Century AD, Emperor Vespasian, who ruled from 69 to 79 AD, ordered the construction of a large amphitheater as part of a plan to boost his popularity in the local region. Vespasian founded the Flavian dynasty emperor after the fall of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. He used public building projects to legitimize his rule as, after Nero’s death, three others had claimed the title of emperor of Rome.

This amphitheater was the third largest in ancient Rome, could seat 50,000 and was modelled on the more famous Colosseum in Rome. It was built near an existing, smaller amphitheater, some of whose remains can still be seen. Researchers believe that the smaller amphitheater was completed during the reign of Nero who died in 68 AD.

For many centuries the amphitheater was the site of games, gladiatorial battles, and public executions. Chariot racing, a widely popular sport in the empire, may also have taken place in the arena. Several Christian saints were martyred during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, including the patron saint of Naples, Saint Januarius.

- A Turbulent Tide Turns In Favor of the Flavian Dynasty

- Pula Arena: Exceptional Roman Amphitheater in Croatia Still Alive and Kicking

- Frozen in Time: Casts of Pompeii Reveal Last Moments of Volcano Victims

Interior view of arena and tiered seating of the Flavian Amphitheater (Enrico Della Pietra/ Adobe Stock)

After Constantine the Great made Christianity the state religion, the amphitheater fell out of favor with the public and it was abandoned through the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. During an eruption of the Solfatara volcano, it was buried by ash and pumice, in a manner reminiscent of Pompeii, which is not far away. Ironically, this probably saved the majority of the Flavian amphitheater.

In the 19th century, the amphitheater was excavated by Italian archaeologists who were amazed to find much of the structure intact and its walls still standing.

The Immense Arena of the Flavian Amphitheater

The amphitheater is elliptical in design and measures 482 feet by 384 feet (147 x 117 m). Its surviving walls are remarkably well-preserved despite them being buried under ash and rubble for many years. Originally these walls would have been much higher and plastered or covered with marble. Much of its marble was quarried and used in other buildings.

A portico, or covered passageway, surrounds the arena. The entrances are still in use and visitors are able to get a good impression of how it looked during the height of the Roman Empire. The arena measures 237 by 139 feet (72 x 42 m) and is surrounded by tiers of stone seats where spectators would sit and watch the grisly games and gladiator battles.

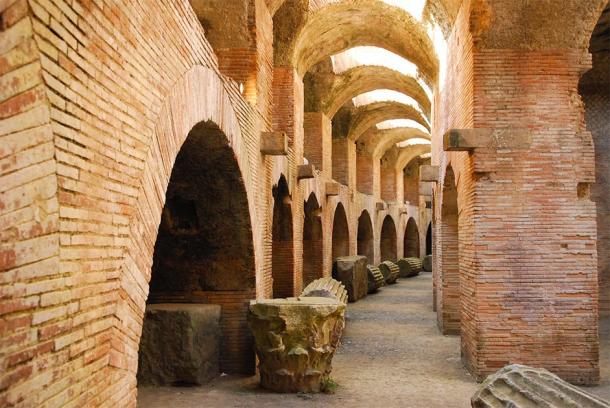

The well-preserved passages beneath the Flavian Amphitheater (Karin Witschi / Adobe Stock)

The warren of passageways beneath the amphitheater, where the wild animals and gladiators would wait before entering the arena, are remarkably well-preserved. It is still possible to see some of the original machinery used to move and direct scenery and those that were used to raise animals, slaves and gladiators up to the arena floor. Unfortunately, the remains of an early medieval chapel which was once part of a larger church, was destroyed by a volcanic eruption.

Visiting the Flavian Amphitheater in Pozzuoli, Italy

The amphitheater is located in Pozzuoli, which is today part of the conurbation of Naples. There is public transport to the area and accommodation is plentiful. An admission fee is charged to enter the amphitheater and many package tours include the amphitheater in their itinerary. Puzzuoli is famous for many classical ruins apart from the amphitheater such as the Temple of Serapide, and of course the crater of Solfatara.

Top image: Ancient gladiator and image representative of the Flavian amphitheater Source: Luis Louro/ Adobe Stock

By Ed Whelan

References

Colletta, T. (2018). The long history of the urban centre and territory of Pozzuoli. BDC. Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini, 18(2), 181-204

Available at: file:///C:/Users/board/AppData/Local/Packages/Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe/TempState/Downloads/6236-Articolo-23638-1-10-20190811%20(1).pdf

D'Arms, J. H. (1974). Puteoli in the second century of the Roman Empire: a social and economic study. The Journal of Roman Studies, 64, 104-124

Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-roman-studies/article/puteoli-in-the-second-century-of-the-roman-empire-a-social-and-economic-study/6855A4DC3FA635264485084C6D0AD301

Dodge, H. (2013). Amphitheatres in the Roman World. A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity, 543-560

Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118609965.ch37