Mound to Mountain: The Long Road to the Great Pyramid

Who built the Great Pyramid? Was it built by simple Egyptian farmers with mud ramps, or aliens, or a lost society from the last Ice Age? Did the ancient Egyptians inherit this massive stone building from a lost time, and then build their own smaller, cruder versions in vain attempts at replicating its awe-inspiring precision? This debate rages on. This article attempts a tempered, reasoned examination of the evidence.

When the Greeks first arrived in Egypt, they were told the Great Pyramid was a tomb for the Pharaoh Khufu, and was already millennia old. Despite many new theories, archaeologists have only confirmed this initial report. They confirmed that the pyramids served as mortuary structures for deceased Egyptian Pharaohs of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (2686-2181 BC), and that the grandest of the pyramids, the “Great One”, was really the result of a centuries-spanning process of trial-and-error, innovation, and ambition, all set within a rich and evolving mythological framework.

The Great Pyramid of Khufu. (Nina Aldin Thune / CC BY 2.5)

Ancient Origins author Ashley Cowie best describes this in his article “Demystifying the Egyptian Pyramids with Hard Facts”. He notes the Great Pyramid was not a fantastical creation from a lost epoch, but fits entirely within its Old Kingdom context. “Practice makes perfect” he says about the pyramids, noting the “scores of ‘failed’ pyramids which speckle the Egyptian deserts”. Let us now go back to the beginning of Egyptian history, and follow the pyramids from their birth. Let us explore their true “origin story”, and follow them through the centuries, from mound to mountain.

The Myths Behind the Mounds

A poem from ~2100 BC speaks of the Pyramids as tombs for the deceased Pharaohs. Called “The Harper’s Song” due to the depiction of a blind harp-player singing it, the poem says:

“The gods (i.e. the dead Pharaohs) who were before rest in their tombs, Blessed nobles too are buried in their tombs.”

The word used for “tombs” is mr, which also translates as “pyramids” and was written using a pyramid hieroglyph.

The origins of the Great Pyramid are believed to lie in ancient Egypt’s complex mythology. In fact, the entire evolution of the pyramids, from mounds to mountains, can be understood within a mythological context. They were places of spiritual ascension and transformation of a god-king.

In the well-known creation story from Heliopolis, City of the Sun, we read that the Egyptian’s early world was completely covered in the lifeless watery abyss of Nun, from which the first dry land emerged. It was upon this first mound, or benben, that the god Atum was “self-created”. In Utterance 600 of the Pyramid Texts, we read: “to say: O Atum-Khepri, when thou didst mount as a hill, and shine on the Bennu of the Benben, in the temple of the Phoenix in Heliopolis, and didst spit out as Shu, and did spit out as Tefnut, then thou didst put thine arms around them, as the arms of a ka, that thy Ka might be in them.”

During the early Second Dynasty (~2880 BC), we find evidence of the pyramidal mound being a symbol of resurrection. An inscription on a statue of Hetepdief, a Memphite priest, depicts two primeval mounds surmounted by solar discs, themselves surmounted by birds of resurrection.

Left, A statue of Hetepdief, a Memphite Priest from the 2nd Dynasty (JE 34557 (CG 1) Cairo Antiquities Museum) bearing inscriptions of two different primeval pyramid mounds surmounted by solar disc and spiritual birds. (Statuen und Statuetten von Königen und Privatleuten im Museum von Kairo, Nr. 1-1294, by Borchardt, Ludwig, 1863-1938; Egypt. Maslahat al-Athar; Volten, Aksel, Berlin, 1911). (Archive.org). Right, Close-up of the two mounds, sun discs, and birds inscribed on the statue.

As Egyptologist and Pyramid expert Mark Lehner notes in his definitive Giza and the Pyramids (2017): “through this connection with the primeval mound, the pyramid is, therefore, a place of creation and rebirth in the Abyss. The (related) verb weben is often used for the sun, as in ‘rise’ and ‘shine’, thereby providing a linkage between the rising of the primeval mound and the solar disc.” (P136).

The pyramid also represented the Sun’s rays, which are described in the Pyramid Texts as a ramp upon which the king mounts to the sky. We can trace the close relationship between the increasing dominance of the sun worship of Heliopolis by the Fourth Dynasty and the development of straight sides on the pyramids. As Lehner notes: “the Pyramid presents a paradox. On the one hand, it is the primeval mound, an image that conveys the entire mass of material creation; on the other, it is immaterial light. This counterpoint runs even deeper as we consider the pyramid as a gigantic capsule of the Duat, the dark Egyptian netherworld.” (P137).

He explores these many dichotomies, odd to our modern senses but beloved by the Egyptians. For example, the cave-like chambers of the pyramids symbolized the darkness of the earth, in which the king’s body was planted like a seed, to ultimately be reborn as a spirit of light. Also, the tomb was the metaphorical womb of the sky-goddess Nut, through which she would birth the king.

The Egyptian word for sarcophagus was neb-ankh or “Lord of Life”, reinforcing the idea of the rebirth expected within the stone monument. Lehner explains the complex ideas present in these buildings: “The paradox of transition from darkness to light and death to life was expressed in stone … in the massive pyramids of the Old Kingdom.” (P139). Where then were the first “mounds” of resurrection in ancient Egypt? Amazingly, hundreds of miles away from the Great Pyramid.

The First Mounds – Egypt before Unification

“For three millennia the Egyptians believed that placing the bodies of their dead under a burial mound gave the departed the seed of renewed life. Just as the first mounds of earth to emerge from the annual Nile flood sprouted new plants, an Egyptian believed the primeval mound represented the fertility from which all creation grew. Planted in the earthen mound of his grave, the king’s mummy, like new seedlings after the withdrawal of the flood, would live again.”

-Mark Lehner, Giza and the Pyramids, 2017; p. 64.

Excavated burial of a lost city near Abydos that dates to 7,000 years ago. (Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities)

To find the original Egyptian mounds, we must travel far to the south of the Great Pyramid. In 2016, as reported by Alicia McDermott on Ancient Origins, archaeologists working near the ancient site of Abydos discovered the ruins of a settlement, including a cemetery of fifteen rectangular tomb structures which were likely covered in burial mounds or mudbrick structures.

However, it was the site’s average radiocarbon date that shocked the team: 5,316 BC. This meant that the first Egyptian burial mounds were at least 7,000 years old, millennia older than previously thought, and that pyramid evolution began over 2,700 years before the Great Pyramid.

- Demystifying the Egyptian Pyramids with Hard Facts

- Remains of a 7,000-Year-Old Lost City Discovered in Egypt

- Archaeologists Announce that New Discoveries Solve Mystery of How the Great Pyramid Was Built

Long before Upper and Lower Egypt were united circa ~3100 BC, separate kings ruled them for centuries, building pit-graves as tombs and filling them with abundant goods. At the site of Nekhen, known to the Greeks as Hierakonpolis, a settlement has been discovered which dates from the Naqada Period (~4400-3000 BC). During this time, we see the development of many of the later Egyptian burial traditions, including multiple compartments for grave goods, mud-plastering and mud-brick walls, colorful paintings (such as T100, Egypt’s oldest painted tomb), wood lining and covering of the burial pit, and, most importantly for us, a tumulus mound above the burial pit.

Archaeologist Barbara Adams has excavated at Hierakonpolis since 1997, focusing on the elite cemetery called HK6 which was previously identified by Michael Hoffman in 1979. Here she discovered a huge tomb, called T23, which was the first to exhibit above-ground funerary architecture. This included both an enclosure wall and a pillared superstructure above the tomb, all made of wooden posts. Her team discovered traces of red and green-painted plaster, and radiocarbon dating placed the structure at ~3790-3640 BC.

We see at Nekhen an increasing focus on the holiness of the sacred mound, for as Mark Lehner explains in the middle of the local temple precinct, Egyptians raised a circular mound of clean sand, 164m (538 ft) across, revetted with limestone blocks. This mound conferred antiquity and was also a key part of the cult of the hawk-god Horus, identified with the ruler. A mud-brick structure was built on top of the mound, and it was under this structure that James Quibell found in 1897 a gorgeous hawk fashioned of copperplate, with head and plumes of gold sheeting.

Lehner suggests this ancient mound was from an early time associated with Horus and the king. The later Pyramid Texts refer to the “Mounds of Horus”, and “the dead king’s soul is told to come to these mounds, to occupy them, to circle around them and to govern them” (p. 64). As the Pyramids Texts say: “Raise yourself, O King, that you may see the mounds of Horus and their tombs.”

Image of the hawk god Horus, fashioned of copperplate with head and plumes of gold sheet; discovered over a sacred mound at Nekhen (Hierakonpolis), it helped connect the mound with Horus and the king (Cairo, Egyptian Museum, JE 32158). (GoShow / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Meanwhile, at Abydos, the tomb of Scorpion I (Tomb “U-j”) was excavated by Egyptologist Günter Dreyer in 1988. Scorpion I was a king of Upper Egypt who died ~3320 BC, and he was buried in a large pit structure, lined with mud bricks with multiple rooms filled with wealthy grave goods like ivory. It would have been covered with cedar logs and likely a large tumulus. Eventually, these mounds of sand over the burial pits were themselves covered in mud-brick superstructures called mastabas, named after the Arabic word for “mud bench”.

Schematic of a mastaba, showing main components: 1) underground burial chamber, 2) separate chamber for the ka statue of the deceased, and 3) a chapel with a false door for the spirit of the deceased to enter and exit. From the Nationalmuseet (Drawing of Ptahwash's mastaba, from: Vesiren Ptah-wash's soul door and his sad destiny / by Elin Rand Nielsen. In: National Museum's field of work; 1993 - Kbh.: National Museum: Poul Kristensen's Publishing House, 1993. pp. 30-43). (Public Domain)

These were flat-topped, steep-sided rectangular mud-brick structures built over the tumulus mounds. The Egyptians called them per-djet, or “House of Eternity”, and they first appeared during these years at Abydos and Saqqara, another early cemetery. The burial pits were dug progressively deeper with each successive pharaoh, up to 6m (20 ft) in the case of Pharaoh Den.

At first, mastabas copied house plans of the day, with multiple rooms for storage of offerings plus the burial chamber itself. By the second and third dynasties, mastabas contained staircases down to the burial pit, as well as ever-expanding courtyards and increasingly complex chambers.

The Royal Cemetery at Abydos, Umm El Qa’ab (“Mother of Pots”) where the graves of the Pharaohs of Dynasties 1-2 were found. (Markh / Public Domain)

A Tale of Two Cemeteries – Abydos and Saqqara

The time period around ~3100 BC remains a confusing one in Egypt’s history, but it was during this time that the lands of Upper (southern) and Lower (northern) Egypt were unified by the Pharaoh Narmer. During this time archaeologists recognize royal tombs and structures not only at Abydos (capital of Upper Egypt), but at Saqqara, a site far to the north, close to the Great Pyramid, near the capital of Lower Egypt, Memphis.

During the First Dynasty (~3100-2900 BC), we see major developments in royal mortuary structures. At Abydos, we find the cemetery Umm El Qa’ab (“Mother of Pots”), Egypt's first royal burial grounds. Egypt’s first Pharaoh, Narmer, was buried here, in a simple two-chamber grave. This pit would have been covered in cedar logs and then covered in a pile of sand which would have been encased in a mud-brick skin (to prevent erosion), creating a burial mound.

Satellite map of the Abydos cemetery, Umm El Qa’ab, with plan of the royal tombs overlain in black. (PLstrom / CC0)

The royal tombs at Abydos were excavated by Flinders Petrie in 1900-1901. He discovered many antecedents to the Great Pyramid, such as the first staircase entrance, granite floor, and stone portcullises. What he failed to find was much evidence of the tombs’ superstructures. These pit graves would have had mud-brick linings, and timber and reed mats covering them, but what covered that?

Drawing of a cross-section through the burial chamber of Pharaoh Djet (Tomb Z), made by Flinders Petrie, showing remains of a mud-brick retaining wall that would have once encased a burial mound of sand and gravel. (Petrie, W.M.F. The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty, 1900-1901, Parts I & II, Cambridge University Press, 2014, originally published in 1901). (Archive.org)

In the tomb of Pharaoh Djet, Petrie discovered enough of a mud-brick wall around the burial to assume it was once covered by a tumulus of sand and gravel. Egyptologist Eva-Maria Engel mentions a “second” tumulus discovered in the tombs of Aha (B15), ‘Snake’ (O), Den (T), and Qa’a (Q), which was “not visible after the end of construction work so that a religious reason for their construction seems plausible”.

Restored tomb of the Pharaoh Den, lacking the original burial mound. (E M. / CC BY 2.0)

This second “hidden” tumulus was also noted in the First Dynasty funerary structures at Saqqara. These took the form of well-preserved mud-brick mastabas. For example, Saqqara mastaba S3507 was excavated by Walter Emery in the 1950s.

Belonging to either Queen Herneith or King Djer, it had a façade built to resemble a colorful palace. It also contained a similar “hidden” mound buried within the mud-brick superstructure. This mound turned out to be a gravel and sand tumulus encased in a mud-brick shell, and it would have been completely hidden when construction was finished. As Egyptologist Barry Kemp noted in 1966: “this tumulus had in time acquired an important magical or religious significance.”

Cross-section drawing of mastaba 3507 of Queen Herneith at Saqqara, including hidden mound; by Walter Emery, 1956. (Emery, Walter B., Excavations at Saqqara: Great Tombs of the First Dynasty Vol III, (Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1958). (Archive.org)

Perhaps the most unusual of the First Dynasty Saqqara “hidden mounds” was in Mastaba S3038 of King Anedjib. Instead of a steep, flat-topped tumulus mound over the burial, it had a unique stepped platform, and many Egyptologists believe it was the inspiration behind the later Step Pyramid.

Left, Drawing of the first version of Mastaba S3038 at Saqqara, built under the rule of Pharaoh Anedjib or Nebetka, showing a distinctive and unprecedented stepped mastaba structure. Right, Drawing of the second stage of Mastaba S3038 at Saqqara, built over the earlier stepped structure, which was retained intact within the later structure. It likely represented the magical primeval mound of resurrection, but in stepped form. (Both figures from Emery, Walter B., Archaic Egypt, Penguin Books, Great Britain, 1961 / Archive.org)

The “double dome” feature of Egyptian graves has been confirmed at Giza during the Fourth Dynasty, in the Worker’s Cemetery. There, graves appear as miniature models of larger pyramids. As Zahi Hawass states :

“We dubbed one remarkable grave the "egg-dome" tomb. An outer dome, formed of mud brick plastered smooth with ‘tafia’, enclosed an egg-shaped corbelled vault built over a rectangular burial pit. What was the meaning of the double dome? Egyptologists believe that mounds left inside large Dynasty I (ca. 2920-2770 BC) tombs and rock protrusions in the pyramids themselves represented a primeval mound of creation that magically ensured resurrection. The same idea may have been in the minds of those who built this tomb.”

Mud Brick Monuments Go Massive

The Second Dynasty meanwhile saw the advent of many new innovative pyramid precedents, and laid the groundwork for their fusion in Dynasties Three and Four. The massive mud-brick funerary enclosure of 2nd Dynasty monarch Khasekhemwy, called Shunet El-Zebib or “House of Raisins”, is 137m (450ft) long, 77m (253 ft) wide, and stands 12m (40 ft) tall, and gives an idea of what the early royal enclosures would have looked like.

Niched wall made of mud-bricks at the Shunet El-Zebib funerary enclosure of Khasekhemwy, at Abydos. (isawynu / CC BY 2.0)

It was likely used for funerary rituals for the king, and was possibly the progenitor of later mortuary temples, built near pyramids. It has niched enclosure walls, typical of later stone walls, which would have been brightly painted.

Egyptologist David O’Connor has excavated at Abydos, working in Khasekhemwy’s enclosure. There he discovered what he believes was once “a large mound made of sand and gravel; it was covered with a brick skin, of which the (recovered) brickwork is the lowest and only surviving piece.” ( Expedition, 1991).

These bricks are tilted upwards, and could have formed the foundation for inclined-accretionary layers of pyramid construction since their angles are similar (~10-15°). He believes that this mound was the prototype of the Pyramid, for it was placed in a nearly identical position relative to the enclosure wall of the later Step Pyramid.

Though rarely discussed in relation to pyramid development, Khasekhemwy was key to many of their later features. He helped to reunify the country after a period of separation, and besides his Shunet El-Zebib, he built a unique tomb nearby at Abydos, the last royal tomb to be built there. It has fifty-eight rooms, and its central burial chamber may be the oldest masonry structure in the world, being built of quarried limestone blocks.

Limestone bricks line the interior of Khasekhemwy’s burial chamber within his tomb at Abydos, the last royal tomb to be dug at the necropolis. (Ioannis Liritzis / Researchgate)

It has been suggested by Günter Dreyer of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo that the central burial chamber supported a tumulus mound, since the walls were compacted to twice the thickness and half the height. This is possibly Egypt’s first stone burial and stone burial mound.

A final shot of the Second Dynasty and its trademark structure, Khasekhemwy’s Shunet El-Zebib. Abydos would never again dominate as the funerary epicenter of the Pharaohs, although some would build temples there, including Seti I. Also, the organization of manpower developed for these structures would greatly help the next architect, Imhotep, when building the Step Pyramid. (Soutekh67, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Thus, by the end of the Second Dynasty, we see all the essential features of the Egyptian burial: a mound of rejuvenating power over the grave, a funerary mound, an above-ground building imitating a royal palace, and a funerary enclosure to protect the funerary mound. Cut stone, like limestone and granite, was also becoming popular as it promised magical protection, security in the form of portcullises, and longevity beyond mud bricks.

However, it would take a genius to finally combine these features, a revolutionary architect who could fuse mounds with enclosures, and who could transform mud buildings into stone ones. He is well known today by his immortal name Imhotep. We will review his achievements when we continue our journey towards the Great Pyramid in the follow up to this article soon.

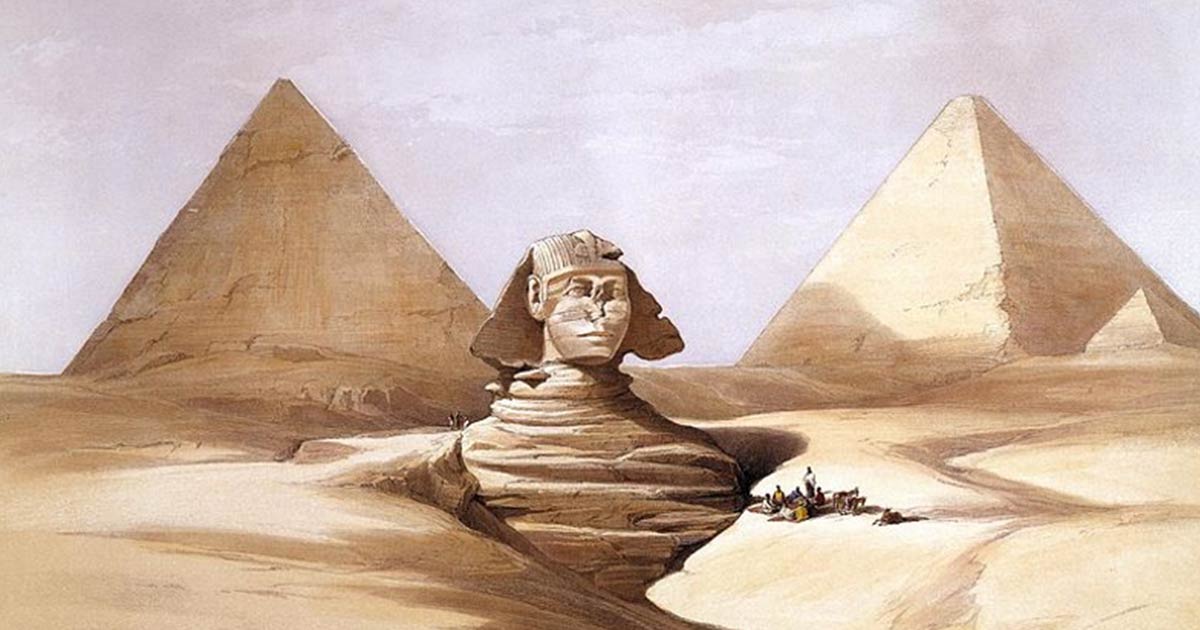

Top image: The Great Sphinx and Pyramids of Gizeh (Giza), 17 July 1839, by David Roberts; 19th century painting of Sphinx of Giza, partly under sand, with two pyramids in the background. Source: David Roberts / Public Domain

Jonathon is a petroleum geologist who has helped excavate numerous prehistoric Native sites in Canada. With a degree in geology and archaeology, his passion is writing about ancient mysteries and uncovering the subverted truths of history. He has penned two books (his first, ‘Moses Restored,’ is on Amazon), and several articles for ‘Atlantis Rising’ magazine under Editor J. Douglas Kenyon.

Ancient Origins Tours provides special access to the enigmatic Sphinx monument and Great Pyramid during private visits in September 2021. Why not join us for this unique experience of a lifetime? The trip will include writer and author Andrew Collins, who first visited Egypt three decades ago, and has conducted many years of work in the country, rediscovering Giza’s lost cave world in 2008, today known as Collins’ Cave.

For more information on the Ancient Origins Egypt Tour click here.

References

Bárta, Miroslav, Journey to the West: the World of the Old Kingdom Tombs of Ancient Egypt, (Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, 2011).

Bestock, Laurel, “The Early Dynastic Funeral Enclosures at Abydos”, In Archeo-Nil, No. 18, March 2008, (https://www.academia.edu/37001333/The_Early_Dynastic_Funerary_Enclosures_of_Abydos).

Bestock, Laurel, The Development of Royal Funerary Cult at Abydos: Two Funerary Enclosures from the Reign of Aha, (Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2009).

Cowie, Ashley, “Demystifying the Egyptian Pyramids with Hard Facts”, Ancient Origins, March, 2018, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/history/demystifying-egyptian-pyramids-hard-facts-009730).

Emery, Walter B., Archaic Egypt, (Penguin Books, Great Britain, 1961).

Emery, Walter B., Excavations at Saqqara: Great Tombs of the First Dynasty Vol I-III, (Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1958) (https://archive.org/details/EXCMEM47/mode/1up).

Engel, Eva-Maria, “The Royal Tombs at Umm el-Qa’ab”, In Archeo-Nil, No. 18, March 2008, (https://www.archeonil.fr/revue/AN18-2008-Engel.pdf).

Gillan, Joanna, “Archaeologists Announce that New Discoveries Solve Mystery of How the Great Pyramid was Built”, Ancient Origins, September 24, 2017, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/archaeologists-announce-new-discoveries-solve-mystery-how-great-pyramid-was-021628).

Isler, Martin, Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids, (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2001).

Kemp, Barry, “Abydos and the Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty”, In The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 52; 13-22, December, 1966.

Lauer, Jean Phillipe, Saqqara: The Royal Cemetery of Memphis: Excavations and Discoveries since 1850, (Scribner, New York, 1976).

Lehner, Mark, and Zahi Hawass, Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History, (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London, 2017).

McDermott, Alicia, “Remains of a 7,000-Year-Old Lost City Discovered in Egypt”, Ancient Origins, July, 2016, (https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/remains-7000-year-old-lost-city-discovered-egypt-007071).

O’Connor, David, “Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins”, Expedition, Vol 33, No. 3, 1991.

O’Connor, David, “Pyramid Origins: A New Theory”, In Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honour of Donald P. Hansen, by Don P. Hansen, Edited by Erica Ehrenberg (Eisenbrauns, Indiana, 2002).

Petrie, W.M.F. The Royal Tombs of the First Dynasty, 1900-1901, Parts I & II (Cambridge University Press, 2014, originally published in 1901).

Stevenson, Alice, “Predynastic Burials”, In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egptology, Willeke Wendrich (ed.), Los Angeles, 2009.

Teeter, Emily, Before the Pyramids – The Origins of Egyptian Civilization, (Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33, The Oriental Institute, Chicago, 2011).

Wilkinson, Toby A.H., Early Dynastic Egypt, (Routledge, New York, 1999 and 2001).