New Research Provides First Peek at Ancient Mesopotamian Drug Use

Medical usage? Ritual practice? Or perhaps the drugs served both purposes? Researchers are asking what the recently recovered psychoactive drug residues from ancient Mesopotamia mean. But not everyone is happy that scholars want to know more.

Dating back 5000 years ago, this is the first concrete example of drug production in the ancient Middle East. Science magazine reports the evidence comes from chemical analysis of residues found on pottery. The findings open doors to the possibility that ancient Mesopotamian drug use may be visible to modern eyes through other means as well.

The researchers discussed the prominence of the use of cannabis, opium, and blue water lily in ancient cultures in a paper for Science. They suggest “the impact of these psychoactive substances has been underestimated and that a drug culture was central to ritual in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Egypt, and the Levant.”

- Prehistoric people used hallucinogens as part of sacred burial rituals

- Getting High with the Most High: Drugs in the Bible

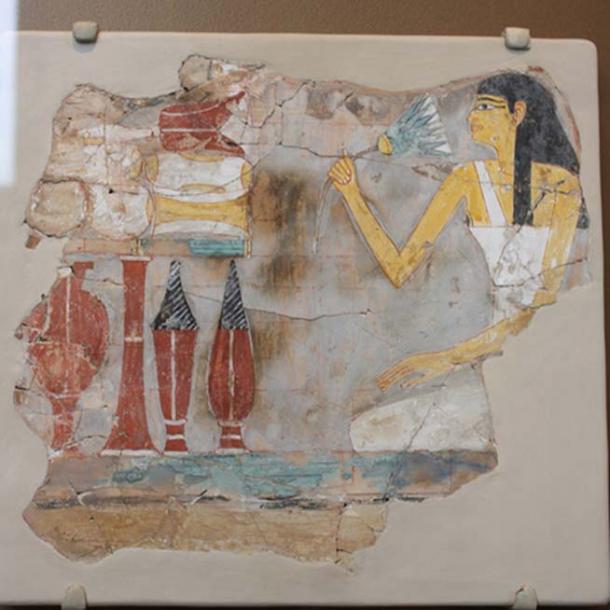

Fragment of a Tomb Painting with Seated Woman Holding a Lotus. (Peter Roan/CC BY NC 2.0)

Archaeologist Luca Peyronel, of the International University of Languages and Media in Milan, Italy, believes that large-scale drug production may have arisen alongside the emergence of the earliest city-states.

Peyronel and his colleagues took samples from pottery found in “an unusual kitchen” of a 4 millennia old palace in the Syrian city of Ebla. They originally thought the room was used for food preparation, but a lack of animal remains led them in a different direction. Continued research provided the traces of wild plants on some of the pots.

When analyzed, the plants were shown to have been medicinal plants such as poppy (for the opium which dulls pain), heliotrope (it’s antiviral), and chamomile (which reduces inflammation). The pots the plants were held in had the capacity for 40 to 70 liters (10.5 to 18.5 gallons) – meaning that a large quantity of the drugs could have been produced at a time.

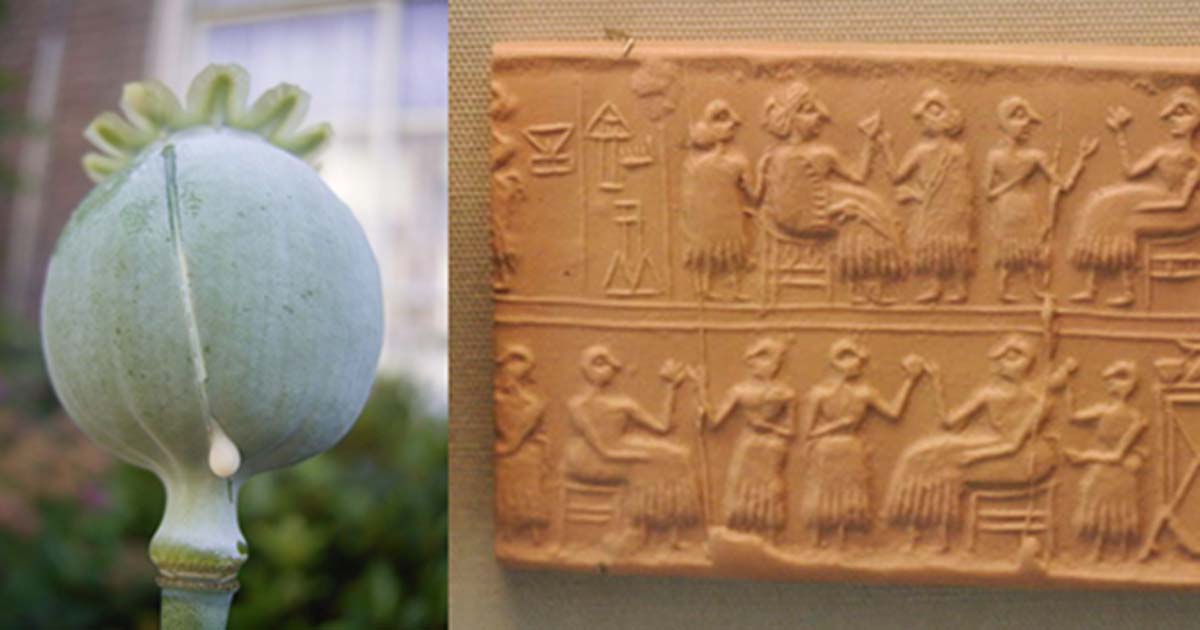

Opium poppy. (Louise Joly/CC BY SA 1.0)

Peyronel says the researchers are uncertain if the drugs were for medicinal, recreational, or ritual use. However, the unusual room’s location at the heart of the palace and cuneiform tablets mentioning priests taking unknown ritual beverages hint that the drugs may have had ceremonial usage. That the drugs were used in both medical and ritual practices makes sense to Peyronel, who explains “The two hypotheses are not necessarily at odds” for the ancient people who prepared them.

David Collard, senior archaeologist at Jacobs, an engineering firm in Melbourne, Australia, also found evidence of opium use on Cyprus. The remnants are younger than those found in Ebla, but they are still over 3000 years old. Analysis of residues in pottery there show that people poured opium alkaloids into poppy seed capsule shaped pots between 1600 and 1000 BC. Those pots were found in temples and tombs, which makes their ritual usage probable.

Cypriot jugs were crafted in the shape of the poppy seed pod 3000 years ago. (Robert S. Merrillees)

By that time, people in Mesopotamia had access to cannabis and ancient Turkish people and Egyptians were experimenting with local drugs such as the blue water lily.

- Archaeological study explores drug-taking and altered states in prehistory

- Secret Chamber Found at Scythian Burial Mound Reveals Golden Treasure of Drug-Fueled Rituals

Ancient texts do not have much to say on the topic, but Diana Stein, an archaeologist at Birkbeck University of London, believes ancient drug use in Mesopotamia has presented itself in other ways. For example, she claims banquet scenes on small seals from Anatolia, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Iran depict psychoactive drug users.

In this Akkadian seal, a seated vegetation goddess is greeted by three other deities. Stalks of grain sprout from the females, while tree branches grow from the males, perhaps referring to a specific myth. (Public Domain)

Collard says that not everyone is interested in exploring the theme of ancient drug use in the region further because “The archaeology of the ancient Near East is traditionally conservative.” Archaeologist Glenn Schwartz at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, agrees, stating “Scholars have tended to shy away from the possibility that the ancient Near Easterners partook of ‘recreational’ drugs, apart from alcohol, so it's good that someone is brave enough to look into it.”

Top Image: A seedhead of an opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, with white latex. (Public Domain) Cylinder-seal of the "Lady" or "Queen" (Sumerian NIN) Puabi, one of the defuncts of the Royal Cemetery of Ur, c. 2600 BC. Banquet scene, typical of the Early Dynastic Period. (Nic McPhee/CC BY SA 2.0)

Comments

One historian said the Romans knew about the analgesic properties of opium when its smoke is inhaled, and when it was available it was used to treat soldiers' battle wounds. It became forgotten knowledge.