Shape Changes, Fear Does Not: The Mythical Monster Coco

Coco is also known in folklore as Cuco, Coca, Cuca, Cucuy. It is a mythical dragon or a ghost monster which is said to appear in many different shapes and forms.

There is no description of the beast which could be applied to all the places where it appears. The origins of Coco are in Portugal and Spanish Galicia, where it is called Coco, and appears as a monster with a pumpkin head, two eyes, and a mouth. In medieval times in the same area, it transformed into a female dragon, which used to take part in different celebrations. In Portugal it has remained popular until today.

The Fight of Saint George and Santa Coca

In the municipality of Monção, near the border with Spanish Galicia, Coco is known as the dragon who fought with Saint George. The feast called Corpus Christi is celebrated on Holy Thursday, and it includes a fight between George and Santa Coca (Coco). If Coco scares Saint George’s horse and defeats him, it is a prognosis for a bad year for the crops. If the horse doesn't react to Coco and Saint George is the winner of the fight by cutting off one of the Coco's ears and her tongue, the crops will be good.

"Festa da Coca" during the Corpus Christi celebration, in Monção, Portugal. (Public Domain)

In Galicia in Spain, there are said to be two dragons, one in Betanzos and the second in Redondela in the Ria de Vigo. According to legend, the dragon arrived from the Ocean and was devouring young women, until he was killed by a group of young men from the cities nearby.

- Outlaws, trolls and berserkers: Meet the hero-monsters of the Icelandic sagas

- Ancient Sea Monsters: Misidentified Fossilized Skeletons Now Revealing Hidden History of Ichthyosaur

- The Legend of the Fearsome Chupacabra in Puerto Rico

Historical Records of the Beast

The tradition connected with Coco comes from ancient times. The story of Coco was most probably described by Diodorus Sicilus (XIII.56.5; 57.3) first. He spoke of the Iberian warriors, who hang the heads of their enemies on their spears. This custom perhaps created the idea of putting heads on sticks as an offering for the beast. The example recorded by Diodorus was the battle of Selinute, which took place in 469 BC, but similar situations happened during many ancient battles in the Iberian Peninsula. According to some researchers, the idea of hanging heads on spears is connected with the Celtiberian culture.

Diodorus Siculus as depicted in a 19th-century fresco. (Public Domain)

The monster perhaps had many other names before the 15th century, when it was called Coco for the first time. The name is said to come from the word ''coconut'' which was given to the fruit by the sailors of Vasco da Gama, but that’s not necessarily the truth. In the book Livro 3 de Doações de D. Afonso III from the year 1274, there is a description of the monster with the use of the name Coca.

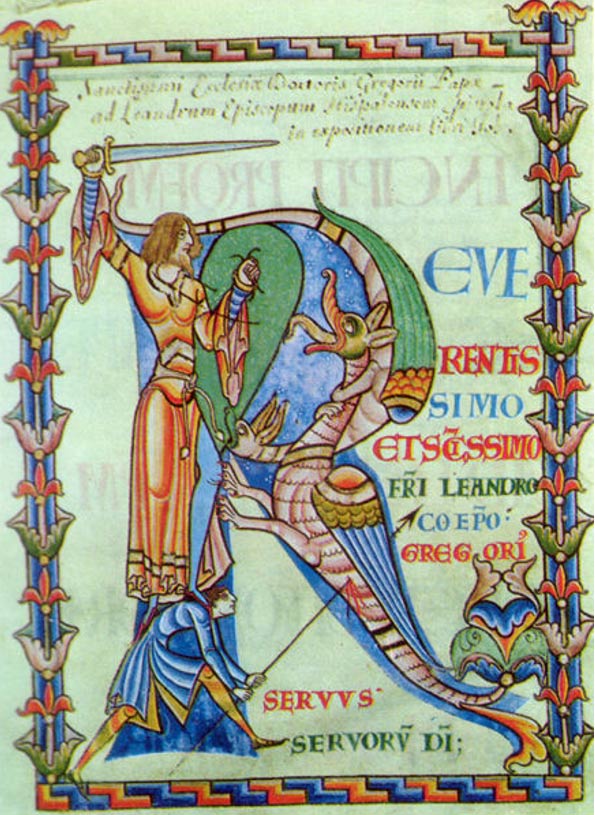

The same dragon, named in medieval times as Cog, was a very common motif in medieval warfare and piracy decor. It appears as a decoration, showing the dragon in both genders. In Catalonia, Coco appears as a zoomorphic figure, which is very similar to a turtle with a dragon head.

Historiated initial R from the frontispiece of a 12th-century manuscript of St. Gregory's Moralia in Job, Dijon, Bibl. Municipale, MS 2. (12th Century). (Public Domain)

A Dragon Which Transformed in the Americas

In Mexico, the fame of Coco arrived with the conquistadors from Spain. Mexican mentality based on traditions with roots in the mythology of the Aztecs and Mayas, understood the topic of a dragon-monster in a completely different way.

It was now considered as an opposite to something like a guardian angel - sort of a boogeyman. There it became an amorphous creature, shaped in different scary forms of dangerous animals. Some folklore legends of Coco from Mexico show the beast as having red eyes and say that it can hide anywhere, even behind the curtains. This Coco hunts for children who misbehave. However, the naughtiest children were said to be hunted by the hungriest and scariest version of Coco - El Cucuy. The child who met him was thought to never return home.

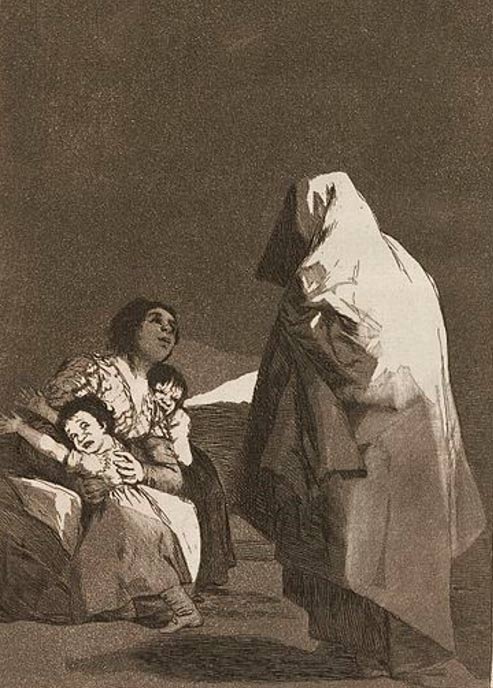

Que viene el coco (Here Comes the Bogey-Man (1799) by Francisco Goya. (Public Domain)

In Brazil, Coco is interpreted as a female alligator known as Cuca. She appears as the villain in many books for children. The story of Cuca is understood the same as in Mexico, but with Portuguese symbolism brought to Brazil through the galleons of the first Europeans.

The Romantic Presentation of the Dragon

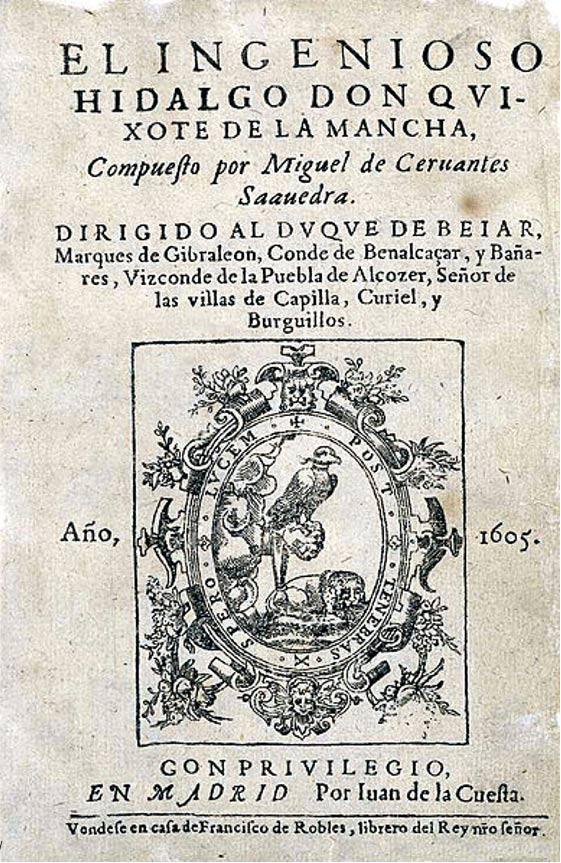

The dragon named Coco also appears in the famous book Don Quijote by Cervantes. The oldest known poem connected with Coco was written in the 17th century by Juan Caxes. In local Portuguese records there is a lullaby by Leite de Vasconcelos (1858 – 1941), who wrote lyrics telling the Coco to go to the top of the roof. There are many versions of the same lullaby, and sometimes the name is changed to "papão negro" (black eater):

Vai-te Coca. Vai-te Coca

Para cima do telhado

Deixa o menino dormir

Um soninho descansado

Leave Coca. Leave Coca

Go to the top of the roof

let the child have

A quiet sleep

Title page of first edition of Don Quixote. (1605) (Public Domain)

El Coco is also very well-known from romantic paintings by the Spanish painter Francisco Jose de Goya, who painted a picture Que Viene el Coco (Here comes the Coco) in 1799. It portrays a monster of a shadowed humanoid. This famous work became an inspiration for hundreds of artists in Spain and Portugal who created a huge number of poems, songs, paintings, etc. from the 17th century until now.

- Doppelgangers and the mythology of spirit doubles

- The Gods of Creation and Legendary Beasts of the Guarani

- Legends say mysterious women built the megaliths of Portugal

The legend of Coco in the 21st century

Even today, parents in Latin America still scare their children by telling them that if they behave badly Coco will come and take them away. Parents also sing lullabies, or tell rhymes related to Coco, which warn children that if they don't obey their parents, Coco will eat them. After centuries, what still scares people about Coco is not its appearance, but the legend that it is a child eater and a kidnapper.

Cucafera during the "Fiesta Mayor de Santa Tecla" in Tarragona, Spain. Source: (Public Domain)

The fame of Coco is so much that it is impossible to mention all the festivals and events where it appears nowadays. Coco is also a common motif in modern popular culture. American guitarist John Lowery composed a track inspired by Coco in 2014, and the American comedian George Lopez mentioned the monster in his two specials. The producers of the TV series Grimm also dedicated an episode to Coco in 2013.

Featured image: Some of the forms of the monster Coco: as a dragon (CC BY SA), with a pumpkin head (Hispanic Culture Online), and as a ‘Boogeyman’ (Framestore)

By: Natalia Klimczak