Akhenaten: Imperishable Art of an Iconoclast: Creativity Blossoms in the Desert—Part I

Never before had a pharaoh ushered daring, almost bizarre and inconceivable transformations in religion and statecraft as Akhenaten did. Not only did he oust the pantheon of traditional gods and shift the royal capital from Thebes to Akhetaten down river in middle Egypt; in doing so, he altered the course of ancient Egyptian history forever. But Akhenaten’s introduction of a new artistic convention continues to captivate viewers down to this day.

Even though little remains in Akhetaten, the once-bustling, defiant capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten; its allure remains unchanged. A restored column in front of the Sanctuary of the Small Aten Temple in Akhetaten. Tell el-Amarna.

Pharaoh Amenhotep IV—(later Akhenaten, reign 1353–1336 BC) the heir of Nebmaatre Amenhotep III of the Eighteenth Dynasty (New Kingdom)—was a determined man who brooked no indifference. In one controversial stroke, the ruler overturned centuries of religious beliefs dear to his people. Every walk of life came under the ambit of Neferkheperure-waenre Akhenaten’s sway. The singular transition that affected the lives of all his subjects was the introduction of Atenism as the state religion, replacing the much-celebrated Amun cult. That was not all: it was decreed that the solar disc would henceforth be the sole and supreme god, and the pharaoh, his earthly intermediary, priest and prophet.

Although Akhenaten’s religious reforms purged Egyptian art of many deities, the King remained fond of the sphinx, and often had himself depicted as that fantastic creature. In the Eighteenth Dynasty, the monument was reinterpreted as the sun god Horemakhet, or ‘Horus in the Horizon’. (Top: Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Below: Hans Ollermann/CC BY 2.0. Museum August Kestner, Hanover, Germany.)

Unlike the legion of Egyptian gods and goddesses, the Aten was not depicted in anthropomorphic form, but was instead represented as a radiant solar disc with a uraeus and rays emanating from it, ending in hands, either left open or holding ankh symbols. Also, the deity’s name was ensconced within a royal cartouche.

A limestone column fragment bears an early name of the Aten within a cartouche. Petrie Museum, London. (Photo: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg)/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Aten was considered both masculine and feminine simultaneously; and more importantly, the Creator of all things. So, while the pharaoh and his queen worshipped the Aten, their subjects worshipped them. This abstract god must have traumatized the ordinary Egyptians, because it meant that the familiar deities who played a role in ensuring their well-being on earth and assured safe passage into the afterlife were obliterated, especially Osiris.

An Amarna period block displays a deeply-engraved relief of the radiant sun disc, the Aten, whose introduction as the sole god by Pharaoh Akhenaten changed the course of Egyptian history. Luxor Temple.

Over thirty centuries later when Amarna revealed itself, modern Egyptologists viewed Akhenaten the flag-bearer of Atenism, variously: while some called him a reprobate and heretic, others were more charitable and looked upon the king as a humanist and monotheist.

James Henry Breasted echoed his sentiments in sparkling prose: “There died with him such a spirit as the world had never seen before. A brave soul, undauntedly facing the momentum of immemorial tradition, and thereby stepping out from the long line of conventional and colorless Pharaohs, that he might disseminate ideas far beyond and above the capacity of his age to understand... who in an age so remote and under conditions so adverse, became the world's first idealist and the world’s first individual.”

One wonders if Akhenaten deserved to be the recipient of such a romanticized view of his reign and policies; for, based on the available evidence, ground realities seem to have been vastly different. Was John Pendlebury right to think the king was a religious maniac?

This FREE PREVIEW is just a taste of the great benefits you can find at Ancient Origins Premium.

Join us there ( with easy, instant access ) and reap the rewards: NO MORE ADS, NO POPUPS, GET FREE eBOOKS, JOIN WEBINARS, EXPEDITIONS, WIN GIFT GIVEAWAYS & more!

- The Many Mysteries of Maya: On the Trail of Tutankhamun’s Valued Courtier–Part I

- Unraveling Tutankhamun’s Final Secret: Cloak of Mysteries Reside in a Sepulchral Masterpiece–Part I

- The Dakhamunzu Chronicles: End Game of the Sun Kings—Part I

- A Dream Destination for Egyptologists: The Amazing Amarna Necropolis

More upcoming in Part II, by independent researcher and playwright Anand Balaji, author of Sands of Amarna: End of Akhenaten.

--

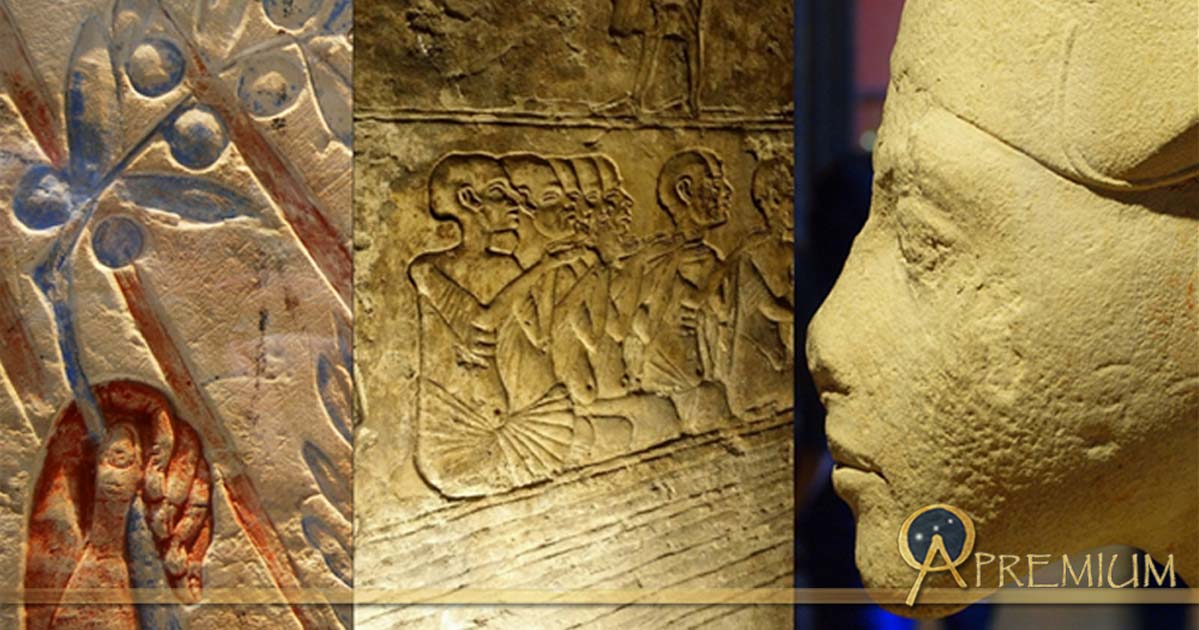

Top Image: Collection of Egyptian Art, design by Anand Balaji (Photo credits: Heidi Kontkanen and Julian Tuffs); Deriv.

By Anand Balaji