King Alaric: His Famous Sacking of Rome, Secretive Burial, and Lost Treasure

The Sack of Rome in 410 AD by the Visigoths is often regarded as an event that marked the beginning of the end of the Western Roman Empire. The man responsible for the second sacking of Rome (the first had occurred 800 years ago in 390 BC, and was carried out by the Gauls under their leader Brennus) was Alaric, the first king of the Visigoths.

It has been said, however, that King Alaric had no intention of conquering Rome, and actually sought to negotiate peacefully. This was done in spite of, or as a means of, avoiding the prophecy which stated that Alaric would control Rome. In Claudian’s poem, The Gothic War, these words are placed in Alaric’s mouth:

“The gods, too, urge me on. Not for me are dreams or birds but the clear cry uttered openly from the sacred grove: 'Away with delay, Alaric; boldly cross the Italian Alps this year and thou shalt reach the city.' Thus far the path is mine. Who so cowardly as to dally after this encouragement or to hesitate to obey the call of Heaven?"

Alaric’s Rise to Kingship

Little is known about Alaric’s early life, although this Visigoth king is thought to have been born around 360 AD. Alaric is also said to have belonged to the family of the Balthi, whose nobility, according to the historian Jordanes was “second only to that of the Amali.” Jordanes also mentions that Alaric was appointed as the king of the Visigoths after the death of the Roman emperor Theodosius I, i.e. 395 AD, due to the increasing contempt of the Romans for the Goths and “for fear their (the Goths) valor would be destroyed by long peace.”

Steel engraving of a young Alaric I. (Public Domain)

The death of Theodosius also marked the end of the peace brokered between the Romans and the Goths. Nevertheless, according to the historian Orosius, Alaric had also sought to make peace with the Romans, as well as to obtain some place for his people to settle in. King Alaric allegedly intended to bring his people into an alliance with the Western Roman Empire against the Eastern Roman Empire as well. None of these wishes were granted.

- Archaeologists Launch Official Search for Treasure of King Alaric Sought by the Nazis

- 1,900-Year-Old Roman Village unearthed in Germany

- Will New Technology Help Relocate the Long Lost Treasure of King John?

King Alaric and the Roman General Stilicho

As a result, Alaric decided to invade Italy, although he was repelled thanks to an able general Stilicho. This general was appointed by the previous emperor, Theodosius, as regent for Honorius, his underage son. However, in 408 AD Honorius had Stilicho and his family executed, as there were rumors that the general was plotting to put his own son on the throne of the Western Roman Empire - with the help of Alaric and his Visigoths.

Carving of General Stilicho with his wife Serena and his son Eucherius. (CC BY SA 3.0)

The death of Stilicho weakened the military might of the Western Roman Empire considerably. Furthermore, Alaric’s army, according to the historian Zosimus, was strengthened when 30,000 Gothic soldiers who were serving in the Roman army defected to the Visigoths. It has been claimed that this mass defection happened as the result of an order given by Olympius, a Roman minister, for the massacre of these soldiers’ wives and children. This same minister has also been blamed for the downfall of Stilicho.

A Siege on Rome

King Alaric invaded Italy for the second time, sacked a number of cities, and stood before the walls of Rome towards the end of 408 AD. He decided to blockade the city, and relied on hunger and disease to force its citizens to surrender. In the meantime, the emperor and his court were in Ravenna (the capital of the Western Roman Empire since 402 AD), and were not directly affected by Alaric’s siege, thus they did little to help the inhabitants of Rome.

In 409 AD, the siege eased when Rome’s inhabitants agreed to pay a ransom to Alaric and his men. According to Zosimus’ account:

“After long discussions on both sides, it was at length agreed, that the city should give five thousand pounds of gold, and thirty thousand of silver, four thousand silk robes, three thousand scarlet fleeces, and three thousand pounds of pepper.”

Additionally, King Alaric was able to raise a puppet emperor, a senator named Priscus Attalus, in Rome, so as to put more pressure on Honorius.

Coin from 409-410 AD depicting Priscus Attalus, King Alaric’s “puppet emperor.” (CC BY SA 3.0)

The ancient sources, apart from Zosimus, do not provide us with much information regarding the events that happened between the first and second sieges of Rome by Alaric. Jordanes’ account for instance, places the sacking of Rome immediately after the destruction of Stilicho’s army, which was sent to ambush Alaric and his men in Pollentia.

Zosimus, on the other hand, provides a detailed report of the events happening during this period. For example, on one occasion, 6000 soldiers, who were quartered in Dalmatia, were ordered by Honorius to come and guard the city of Rome. Their general Valens felt that it was cowardly to “march by a way that was not guarded by the enemy” and was attacked by Alaric, which reduced the former’s army to about a hundred men. Unsettled negotiations between Honorius and King Alaric continued for some time, but eventually they reached a dead-end.

- Exploring the Origins of the Vandals, The Great Destroyers

- Everything he Touched Turned to Gold: The Myth and Reality of King Midas

- The Sumerian King List still puzzles historians after more than a century of research

The Second Attack by King Alaric on Rome

In 410 AD, Alaric attacked Rome for the second time. Unfortunately, Zosimus’ work has not survived in its entirety, and King Alaric’s sack of Rome, which is said to be the last part of Zosimus’ work, is now lost.

An extract taken from a Renaissance writer suggests that Alaric besieged Rome for two years, and finally used a ‘Trojan Horse’ tactic to take the city. Instead of a giant wooden horse, however, the gift of the Visigoths was “three hundred young men of great strength and courage, whom they bestowed on the Roman nobility as a present,” before pretending to return home.

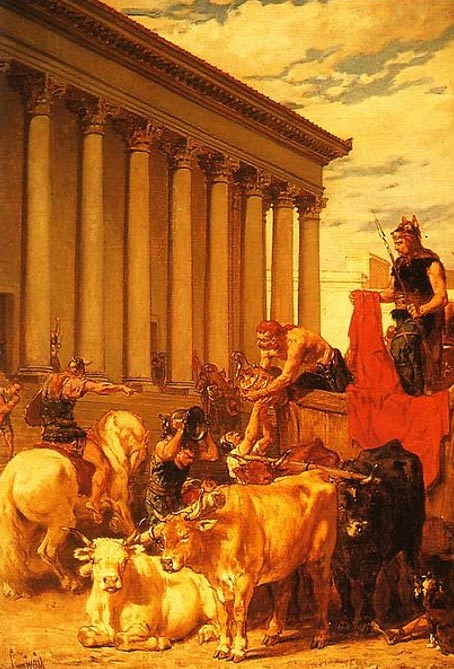

Much focus has been placed on the Visigoths’ conduct during the sacking of Rome. Jordanes, for example, wrote that, “by Alaric's express command they merely sacked it and did not set the city on fire, as wild peoples usually do, nor did they permit serious damage to be done to the holy places.”

“The Sack of Rome” in 410. By Évariste-Vital Luminais. (Public Domain)

This is also echoed in Orosius’ writing, in which Alaric is presented as a pious Christian king. One fantastic tale in Orosius’ account is the encounter of a Visigoths with an elderly virgin, who turned out to be the keeper of the sacred vessels of the Apostle Peter. When Alaric heard of this, he had these vessels brought back to the basilica of St. Peter, and even allowed the virgin and other Christians to join the procession if they wished to do so.

The Secret of King Alaric’s Burial and Treasure

Alaric died in 411 AD, several months after sacking Rome. The following story of Alaric’s burial comes from Jordanes’ account:

“His people mourned for him with the utmost affection. Then turning from its course the river Busentus [Busento] near the city of Consentia - for this stream flows with its wholesome waters from the foot of a mountain near that city - they led a band of captives into the midst of its bed to dig out a place for his grave. In the depths of this pit they buried Alaric, together with many treasures, and then turned the waters back into their channel. And that none might ever know the place, they put to death all the diggers.”

Illustration of the burial of Alaric in the bed of the Busento river. (1895) By Heinrich Leutemann. (Public Domain)

Scholars have often wondered about King Alaric’s cause of death. Recently, Francesco Galassi and his researcher colleagues poured over all the historical, medical, and epidemiological sources they could find about the king’s death. They think they have discovered the reason for King Alaric’s sudden death - malaria.

Galassi and his colleagues explained that “Individuals with semi-immunity in hyper-endemic and endemic areas can spontaneously clear the parasite.” But apparently the people who went to ancient Italy from malaria-free areas were in extreme danger. They write, "Several cases of sudden deaths in travellers coming from malaria-free areas have been reported in Africa” and “severe falciparum malaria progresses to death within hours or days from the onset of the symptoms, with major complications such as cerebral impairment, pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, and severe anemia.”

The immense wealth that many scholars believe was placed alongside King Alaric has provoked various treasure hunts over the years. Some of the famous treasure seekers of the past include the writer and adventurer Alexandre Dumas and the Nazis Adolph Hitler and Heinrich Himmler. Despite their best efforts, none to date are said to have found the location of King Alaric’s burial, although the recent commissioning of a team of archaeologists by the town of Cosenza may finally bring King Alaric’s loot to light.

Featured image: King Alaric entering Athens. Photo source: (Public Domain)

By: Ḏḥwty

References

Cavendish, R., 2010. The Visigoths sack Rome. [Online]

Available at: http://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/visigoths-sack-rome

Claudian, The Gothic War [Online]

[Platnauer, M. (trans.), 1922. Claudian’s The Gothic War.]

Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Claudian/De_Bello_Gothico*.html

Gill, N. S., 2015. Alaric King of the Visigoths and the Sack of Rome in A.D. 410. [Online]

Available at: http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/alaricthevisigoth/a/AlaricSackRome.htm

Heather, P., 2011. Rome's Greatest Enemies Gallery: Alaric. [Online]

Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/enemiesrome_gallery_01.shtml

Jarus, O., 2014. Who Were the Ancient Goths?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.livescience.com/45948-ancient-goths.html

Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths [Online]

[Mierow, C. C. (trans.), 1908. Jordanes’ The Origin and Deeds of the Goths.]

Available at: http://people.ucalgary.ca/~vandersp/Courses/texts/jordgeti.html

Paulus Orosius, A History, Against the Pagan: Book 7 [Online]

[Anon. (trans.), ?. Paulus Orosius’ A History, Against the Pagans: Book 7.]

Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/demontortoise2000/orosius_book7

Zosimus, New History: Book 5 [Online]

[Anon. (trans.), 1814. Zosimus’ New History: Book 5.]

Available at: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/zosimus05_book5.htm

Zosimus, New History: Book 6 [Online]

[Anon. (trans.), 1814. Zosimus’ New History: Book 6.]

Available at: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/zosimus06_book6.htm

Comments

this is super idiotic, we alll know its kill or get ded