Did Hatshepsut, Number-One Female Pharaoh, Have a Secret Lover?

Perhaps the greatest female pharaoh other than Cleopatra VII, Hatshepsut (ruled 1473-1458 B.C.) was not the first woman to take power as sole monarch in the Two Lands. But Hatshepsut made a true name for herself—despite her nephew/stepson Thutmose III’s attempts to erase it!—and those she loved, including her chief minister (and possible lover), Senenmut.

Feeling Hat, Hat, Hat

First, a bit of backstory. Hatshepsut’s ancestors of the Eighteenth Dynasty helped reunify the Two Lands of Egypt and left a legacy of powerful monarchs—and powerful women. Ahhotep, mother of the warrior pharaoh Ahmose I, wielded great political and religious influence, even earning military honors for herself; Ahmose-Nefertari, Ahmose’s sister and wife, served as a regent and was even deified. As Egyptologist Kara Cooney notes in her recent biography of Hatshepsut, The Woman Who Would Be King, the rulers of the first half of the Eighteenth Dynasty were among its most famed warriors and conquerors.

Hatshepsut was born to Pharaoh Thutmose I, probably of non-royal parentage, and his Great Royal Wife Ahmose (likely a royal relative), sometime between 1508 and 1500 B.C. Hatshepsut’s birth came at a time of great growth for Egypt. Ahmose bore Thutmose I only daughters, so, when he died around 1492 B.C., his son by a lesser wife, Thutmose II, succeeded him.

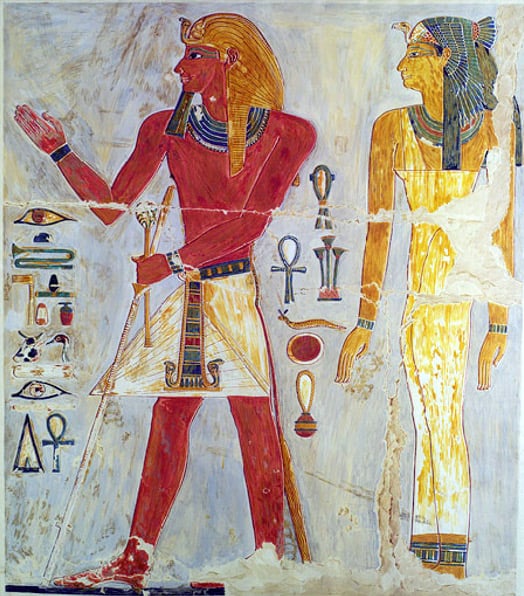

Thutmose I, as portrayed in Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. Image via Paul James Cowie/Wikimedia Commons.

To consolidate his power, the new king married his half-sister, Hatshepsut, who brought royal blood and authority to the match; such incestuous intermarriage was common amidst the ruling house of Egypt. The women of a pharaoh’s family didn’t marry outside the family, usually wedding the king himself (just check out the Amarna Letters!). Like her mother, Hatshepsut only had girls: one daughter, Neferure, who wed her own half-brother, Thutmose III. That future king was Thutmose II’s son by—you guessed it!—a lesser wife.

Custom had it that, if a pharaoh died while his heir was still young, a queen might serve as regent during his minority. And that’s just what Hatshepsut did for her stepson…but about seven years later, she started adopting pharaonic titles herself—perhaps, at first, to secure power for little Thutmose—and eventually declared herself king. Often depicting herself in royal statuary as a male with regal trappings, she called herself the “Son of [the sun god] Re, Hatshepsut Khenemet-Amun , given life by Re forever,” as she claimed on a monument at the Temple of Karnak.

Her Man the Minister

One of Hatshepsut’s closest advisers, her chief steward, was a commoner-turned-politician named Senenmut. He first entered Hatshepsut’s household during Thutmose II’s reign and became the tutor to her only child. His close relationship with Neferure came across in the ten statues he commissioned portraying himself with her. Quite a few depict him holding her on his lap or sitting behind her as a guardian, emphasizing his literal closeness to the royal family and the great trust they had in him. Elsewhere, he calls himself “a dignitary beloved of his lord…he ennobled me in front of the Two Lands and made me the chief spokesman of his estate and judge in the entire land.”

Senenmut hugs Neferure in a statue from the British Museum. Image via Lenka P/Flickr.

Senenmut also held high positions in the Temple of Amun, the most important religious institution of this time, supervising its vast wealth. He also oversaw the erection of Hatshepsut’s obelisks at Karnak and probably played a major role in the construction of her funerary complex at Deir el-Bahri; one monument, now in the British Museum, calls Senenmut the “Overseer of All Works of the King.”

Perhaps most indicative of their close relationship was the fact that he had his name carved in Djeser-Djeseru, Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple…and that he built one of his two tombs near Deir el-Bahri. A graffito from Aswan, where Senenmut supervised the quarrying of granite, even shows the two face to face. It seems that he wanted to remain close to his mistress forever, even in the afterlife.

Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. Image via MusikAnimal/Wikimedia Commons.

But were these extraordinary honors indicative of a sexual relationship? Hatshepsut never remarried and Senenmut apparently didn’t ever take a wife; as Cooney points out, the pharaoh may well have had lovers whose names we don’t know. A graffito on a tomb near Deir el-Bahri showed an unnamed man having sex with an anonymous woman, perhaps wearing a royal headdress, from behind.

Unfortunately for the Hatshepsut-Senenmut shippers in the crowd, though, these individuals are not named. There’s also no evidence indicating the graffito is from Hatshepsut’s time, so we have no proof that they were the pharaoh and her minister. Even if they were explicitly named, though, who says the artist was telling the truth?

After Hatshepsut’s deaths, Thutmose III ordered her name inscribed on monuments to be erased. Some of Senenmut’s monuments were destroyed, but their defacement was inconsistent. Sometimes his name was removed and his sarcophagus was wrecked, while other statues were intact. Did Thutmose do it? Some claim Hatshepsut herself turned on Senenmut and wrought havoc.

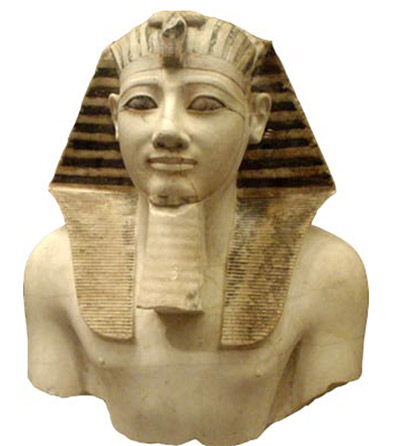

Hatshepsut’s son, Thutmose III, tried to have all traces of her wiped from history. Image source: Wikipedia

What purpose did obliterating a man’s name serve? The Egyptians thought that preservation of the name was absolutely vital to the soul’s survival; it was, in truth, a part of the deceased’s self. By eliminating the names of the woman who usurped his throne and (perhaps) her chief servant, Thutmose damned them for eternity. But Senenmut’s legacy survived as part of Hatshepsut’s epic reign.

Top image: Hatshepsut by catch22/deviantart

By Carly Silver

References:

Cooney, Kara. The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut's Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. New York: Crown, 2014.

Graves-Brown, Carolyn. Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. New York:Continuum, 2010.

Roehrig, Catharine H., ed. Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York:Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

Taterka, Filip. “Hatshepsut and Senenmut or the Secret Affairs of Egyptian State.”

Cupido Dominandi: Lust for Power—Power Over Lust, May 2014, University of Warsaw , Warsaw, Poland. 2015.

Van de Mieroop, Marc. A History of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2011.