The enduring mystery of The Lady of Dai mummy

When talking about body preservation and mummies, people all over the world think of Egypt and the mummified bodies of Pharaohs, such as Tutankhamun. But how many know that the world’s best preserved bodies actually come from China? The Lady of Dai, otherwise known as The Diva Mummy, is a 2,100-year-old mummy from the Western Han Dynasty and the best preserved ancient human ever found. Just how this incredible level of preservation was accomplished has baffled and amazed scientists around the world.

In 1971, at the height of the cold war, workers were digging an air raid shelter near the city of Changsha when they uncovered an enormous Han Dynasty-era tomb. Inside they found over 1000 perfectly preserved artefacts, along with the tomb belonging to Xin Zhui, the wife of the ruler of the Han imperial fiefdom of Dai.

Xin Zhui, the Lady of Dai, died between 178 and 145 BC, at around 50 years of age. The objects inside her tomb indicated a woman of wealth and importance, and one who enjoyed the good things in life. But it was not the precious goods and fine fabrics that immediately caught the attention of archaeologists, rather it was the extraordinarily well-preserved state of her remains that captured their eyes.

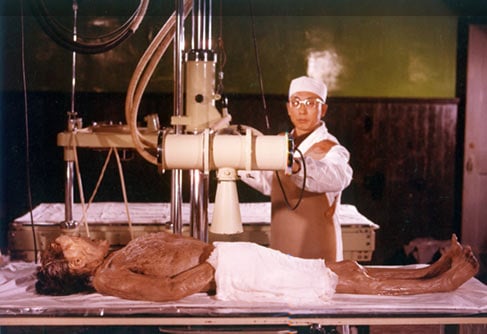

Despite the fact that she had been buried for over two millennia, her skin was still moist and elastic, her joints still flexible, every feature still remained intact down to her eyelashes and the hair in her nostrils, and blood still remained in her veins. When she was removed from the tomb, Oxygen took an immediate toll on her body and so the state in which she is seen today does not accurately reflect how she was found. Nevertheless, when forensic scientists conducted an autopsy on the Diva Mummy, they were stunned to discover that the body was in the same state as an individual who had recently died.

The Lady of Dai undergoing examination. Photo credit: Hunan Provincial Museum

The autopsy revealed that all her organs were still intact, even down to the lungs vagus (nerve), which is as thin as hair. Blood clots were found in her veins and evidence was found of a coronary heart attack, as well as a host of other ailments and diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, liver disease, and gallstones. The Lady Dai died of a heart attack at the age of 50, brought on by obesity, lack of exercise and an over-indulgent diet.

When they were still studying her organs, the pathologists found 138 undigested melon seeds in her oesophagus, stomach, and intestines. Melon seeds take about 1 hour to digest so scientists were able to determine that she died shortly after eating some melons.

Archaeologists and pathologists have not determined all the factors behind her state of preservation, but they have a few clues.

A well-sealed tomb

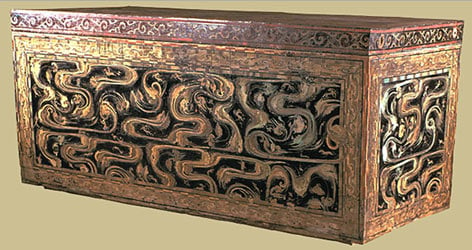

Lady Dai was found in an airtight tomb 12 metres underground, locked inside four layers of coffins. A thick layer of white paste-like soil was on the floor. Her body had been swaddled in 20 layers of silk and she was found in 80 litres of an unknown liquid that was mildly acidic with some magnesium in it. The layers of caskets were put inside a compartment in the centre of a funnel shaped, clay lined, massive cypress, burial vault. Five tons of moisture absorbing charcoal was packed around the vault. The top was sealed with 3 feet of additional clay. Hard rammed pieces of earth filled the shaft all the way to the surface.

No substance of any kind was able to get in or out of the sealed tomb. Decay-causing bacteria trapped inside would quickly die because of the lack of oxygen. Destructive ground water could not penetrate the sturdy barriers. The result of such diligent hard work that went into sealing and protecting the late Lady Dai, was a cool, highly humid, almost sterile, environment.

The Coffin of the Second Layer. Photo credit: Hunan Provincial Museum

Precious valuables

Archaeologists found Lady Dai's burial chamber filled with more than 1,000 precious goods – fine fabrics, bizarre delicacies (such as caterpillar fungus), a complete wardrobe of more than 100 silk garments, 182 pieces of lacquer ware, and 162 carved wooden figurines that represented the large army of servants who would tend to her needs in the after world. The opulence found within the tomb revealed a world where the rich and powerful not only desired to live forever – they expected to.

The lacquer ware was regarded as the most precious of all manufactured goods. The collection of plates, bowls, trays, vases, basins, and toilet boxes were all part of the treasures, their deep black and bold red coating almost as perfect as the day it was buried.

A lacquered item, as lustrous as the day it was buried. Photo credit: Hunan Provincial Museum

The Lady Dai was also buried with a massive array of foods and fine cuisine stored in thirty bamboo cases and several dozen pottery containers, including: wheat, lentils, lotus roots, strawberries, pears, dates, plums, pork, venison, beef, lamb, hare, dog, goose, duck, chicken, pheasant, turtledove, sparrow, crane, fish, eggs, and owl. The common people of this time period ate nothing of the sort. Their diet had basic wheat, millet, barley, and soybeans.

China’s eternal mummy

While the factor’s surrounding Lady Dai’s burial appear to solve the question as to how such an incredible state of preservation was achieved, scientists today have not been able to replicate it using modern methods, nor have they discovered the source of the mystery fluid found within the tomb. In fact, other tombs containing bodies similarly preserved were found within a few hundred miles of Lady Dai, but each time the liquid appeared to have different properties. Whatever the ancient morticians did, they managed to create China’s eternal mummy, the Lady of Dai, who is now housed in the Hunan Provincial Museum. Visitors flock from all over the world to share in gazing at the amazing sight of a Lady Dai's well preserved body and the intriguing pieces of Chinese history she left behind.

Top Image: The Lady of Dai. Photo Credit: Hunan Provincial Museum

References

The Diva Mummy – Off the Fence

The Long Lasting Remains – Hunan Provincial Museum

The Discovered Body & Tomb of Lady Xin, the Marquise of Dai – by Rana Wiseone

Lady Dai Tomb Among Richest Finds In China History – by Sue Manning

The Diva Mummy – The Mummy Blog

Related Videos

Comments

So apparently the Chinese have nearly always had a Roman-like fixation on extravagant meat dishes. Odd paradox for a country that suffered so many famines and food shortages.

Just as spaceships have done weird things in Bendigo, Australia, the contention of a Divine Joke bears examination. Look at her name! Lady Die, Lady Die- !!

There are other questions, if this is a genuine burial and not another of God’s little jokes!

First of all, was she murdered? You have to ask this question because the scenario is unreal. Ask yourselves just exactly how long it would take to fashion the layers of coffins, and the tomb’s construction itself. Months, if not years of labour- as the coffins are finely made and the vault rigorously contructed and prepared. Or did they know she was dying and say, “Ma’am, fancy being dug up all freshly dead in two millenia? Satisfaction guaranteed, you’ll be an absolute wow!!”

And get it all ready for her?

There was no belief that dead Egyptians needed their old bodies in their old form, they needed a body that was going to last FOREVER. Those shriveled up, blackened bodies that you see as a failure of mortuary engineering are actually exactly what their religion called for: a vessel in this world for an immortal soul to have permanent access to should it need anything.

This demonstrates how to preserve a body effectively, whereas the Egyptian obsession demonstrates the failure to do so at all. Fascinating.

I am VERY surprised indeed that the fluid is still unidentified. Perhaps the chinese, idiotically, are keeping it to use themselves after they have choked on caterpillar fungi omelette with shredded rhino horn, or, of course, their own brand of the deadly pollutions that copying us, they are using to cripple their own and their children’s health.

Interestingly is Egypt made more of a weird headspace to go than ordinarily, because Lady Dai really does bring home the fact of the failure of the mummification processes there. More to the point, it unmasks problems with their chronology.

Listen up folks. Mummies in Egypt are dateable over thousands of years. Therefore, fellow sufferers, it stands to reason, that those expecting to be mummified, or mummified with or without their pets, falcons etcetera, were in fact surrounded, whilst alive, with the dead, ugly, decomposing and certainly not well-preserved mummified remains of anyone whose family could pay the price, and so they MUST have known the process itself didn’t work at all. Grave robbers (IS is no new thing) knew that even royal mummies were just dried up rubbish.

So why did they bother exactly? Why not just bury, or cremate, or expose the remains in the desert (as do Parsees and some Tibetans still)?

Pages