Living God in a Wooden Box: In Whose Coffin was Ramesses II Buried?

Usermaatre Setepenre Ramesses II, the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, was one of ancient Egypt’s longest-reigning monarchs. In an astonishing sixty-seven regnal years – the glory days of empire that witnessed unprecedented peace and prosperity – the monarch built grand edifices and etched his name on innumerable monuments of his forbears. Whether it was reverential usurpation or the king’s desire to broadcast his power; the fact remains that few rulers matched his magnificence and propaganda skills. And yet, for a man who strode the world stage like a colossus, the mummy of Ramesses was found in an ordinary wooden coffin that belonged to another king. How and why did this come about; and who was the original owner of the casket?

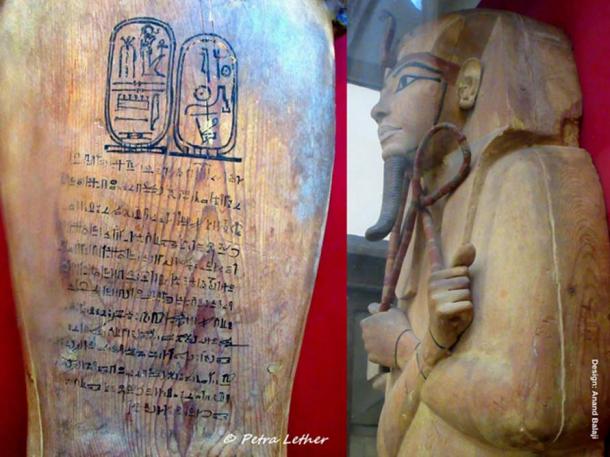

Wooden coffin lid of Rameses II (Usermaatra Setepenra, 1279-1213 BC) of the 19th Dynasty from Deir el Bahari. (Image credit: S. Hayter, ancient-egypt.co.uk, accessed Jan 2018).

Equipped for the Afterlife

Ramesses seems to have continued his penchant for usurpation posthumously too — albeit, without his stir! By the time he perished at the ripe old age of 90, or thereabouts, the pharaoh had built a sumptuous tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings (KV7) which rivalled that of his illustrious father, Seti I (KV17). Ramesses lay in regal splendor in the hallowed confines opposite the sepulcher of his predeceased sons (KV5) — a tomb examined only partially in modern times by two British Egyptologists: James Burton in 1825, and later Howard Carter in 1902. Re-discovered in 1995 by Dr Kent Weeks who headed the Theban Mapping Project, KV5, that contains 200 corridors and chambers proved to be the largest crypt at the site. Also, as of 2006, nearly 130 rooms were brought to light thanks to the enormous efforts of Weeks and his team.

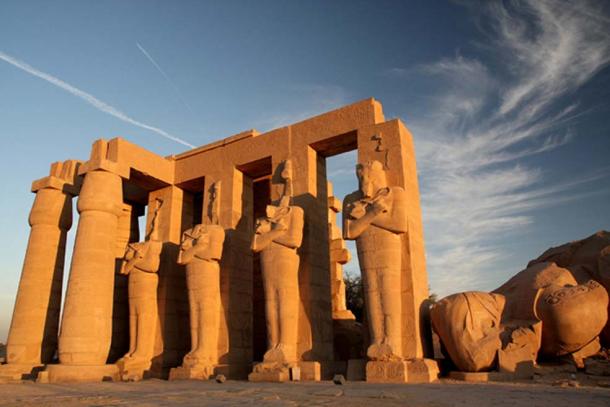

The imposing Ramesseum built by Ramesses II is a UNESCO World Heritage Site today. This memorial temple was originally called the House of Millions of Years of Usermaatra-setepenra. Pictured here are headless Osiride statues of the pharaoh. (CC BY 2.0)

But, despite his preparations, the Afterlife posed serious challenges for Ramesses II. His massive House of Eternity did not survive looting in antiquity; nor was it spared by the vagaries of nature. The former acts in the royal necropolis at the close of the Twentieth Dynasty and the beginning of the early Twenty-First Dynasty were mostly state-sanctioned.

- The Life and Death of Ramesses II

- The Women Who Created a Legendary Pharaoh: The Hidden Advisers of Ramesses II

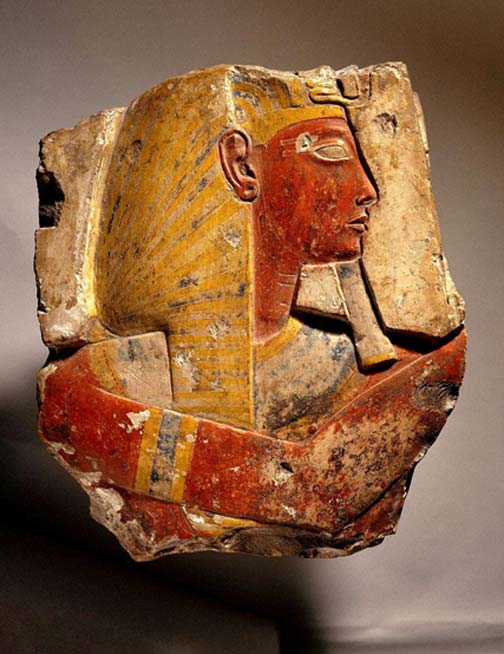

The color and style of this relief strongly suggest not only that it originated from the temple of Ramesses II at Abydos, but also that it was carved in the first two years of his reign, perhaps by the same artists who decorated the adjacent temple of his predecessor, Seti I. (Image: Brooklyn Museum)

In a time when Egypt faced the threat of internal rebellion, poverty and diminishing respect among vassal states, the priest-kings who usurped power needed wealth to fulfill their ambitious building projects. With sources of revenue drying up fast, they hit upon a devious plan to fill the coffers in the form of bullion stocked in the tombs of their predecessors. This was ransacking under the guise of pious restoration.

- Cartouche purchased for £12 may be precious seal of Ramesses II

- Revealing the Ramesseum Medical Papyri and Other Remarkable Finds from the Temple of Ramesses II

The mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu functioned as a workshop for rewrapping many royal mummies during the official ‘restoration’ period. This image was shot during an aerial survey of the West Bank in 2010. (Image: ©Howard Middleton-Jones)

“The manner in which the royal dead and their coffins were treated by these salvage teams could be ruthless in the extreme,” reveals Dr Nicholas Reeves, and adds, “An important point to note, however, is that not all of the royal dead and their coffins had been treated in such a devastating way: along with those bodies which were hacked and badly broken, the DB 320 Cache yielded some of the best-preserved mummies ever found, including that of Ramesses II which had, of course, travelled to its final resting place within the coffin Inv. Cairo CG 61020.”

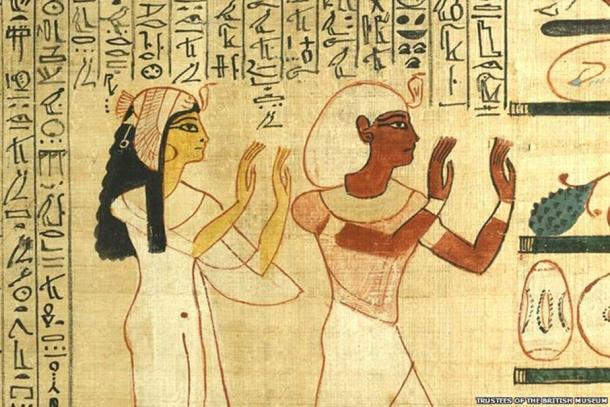

King Herihor, the erstwhile Theban High Priest, and Queen Nodjmet adore Osiris in the Afterlife. From the Book of the Dead papyrus of Nodjmet, c. 1050 BC. (Image courtesy of British Museum.)

Assault on the Royal Necropolis

In fact, the violation of these sacred sanctuaries was not new, for much earlier, tomb robbers struck at several Seventeenth Dynasty burials in the Valley of the Queens and the mortuary temples of deceased kings. “Old royal mummies were removed from their original tombs, often rewrapped, and moved to hidden caches. In the process of rewrapping, those carrying out the scheme removed the gold, jewels, and amulets from the mummies, along with anything else considered of value in the tombs. Some have called this process preservation, others plundering, or a combination of the two,” informs George Wood. The mortal remains of Ramesses the Great too suffered this fate.

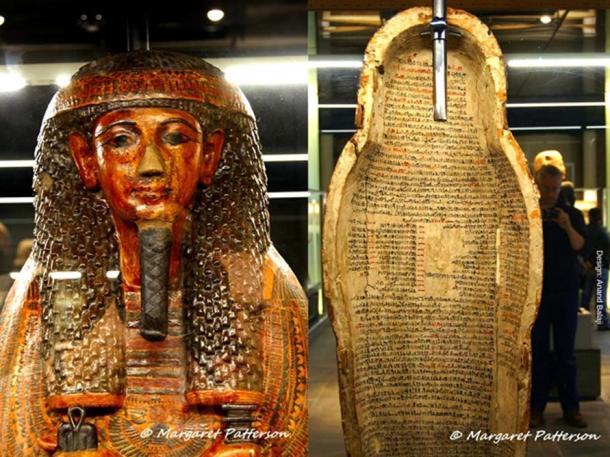

The richly decorated front and text-filled inside of the coffin of Butehamun, scribe of the royal necropolis. Third Intermediate Period, 21st Dynasty. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. (Images courtesy of Margaret Patterson)

During this ‘Great Restoration’ (Whm Mswt - literally translated as Repetition of Births) the king’s body was whisked away to a holding area - most probably Medinet Habu, Ramesses III’s sprawling mortuary temple - where his mummy was stripped of valuable materials. Reeves explains that the unfinished KV49 sepulcher, and the abandoned tomb of Ramesses XI (KV4) were also used as workshops during the recycling project.

“In the fourth year of Herihor’s rule (1066 BC), the necropolis scribe Butehamun received an order to carry out “work” in the tomb of Horemheb. It was the beginning of the end for the royal graveyard. Over the next decade, the tombs of the New Kingdom pharaohs were emptied one by one. The workmen who carried out the task even seem to have had a map of the valley (surely provided by the authorities) to assist the clearance. Their main objective was to expropriate the large quantities of gold and other valuables buried in the Theban hills.

Mummy and inner coffin of King Amenhotep III. The lid had originally belonged to Seti II and the coffer to Ramesses III. The apparent carelessness and haste with which Butehamun carried out the ‘restoration’ is obvious. (Image: G. Elliot Smith, Public Domain,)

“These were swiftly removed to the state treasury, leaving only the mummies—rudely unwrapped in the search for hidden jewels—to be taken to Butehamun’s imposing office at Medinet Habu for processing and rewrapping. Little wonder that Butehamun was proud to call himself, without a hint of irony, “overseer of the treasuries of the kings.” So rife was tomb robbery in the Theban necropolis at this time that private individuals designed their interments with an obsessive emphasis on inaccessibility, to make the robbers’ job as hard as possible,” notes Toby Wilkinson.

In 1881, this plain-looking shaft in Deir el-Bahari led Émile Brugsch to DB320 where the most extraordinary cache of royal mummies lay concealed for millennia. (Inset) Brugsch is in the center overseeing the removal of the contents, while Sir Gaston Maspero (seated) looks on. (Images: Keith Hazell/CC BY 3.0 and Wikimedia Commons)

Butehamun and his father Djehutymose were tasked with not only divesting the royal dead of their valuables, but were ordered to seek a safe hiding place in which to house the mummies after they were rewrapped. Butehamun assessed that KV35 – the burial place of Amenhotep II that was discovered in 1898 by French Egyptologist Victor Loret – would be ideal. Thus, in c. 1050 BC, the divested mummies of several pharaohs were laid to rest a second time in this massive tomb. In the process, Amenhotep III ended up in a coffin inscribed for Ramesses III, with an ill-fitting lid made for Seti II. A second cache of mummies from this restoration period was found in DB320, the unfinished tomb located in the Theban plateau just south of Deir el-Bahari.

For all the pomp and regal authority he exercised, Ramesses the Great was ultimately laid to rest in a simple cedar wood coffin. Hieratic inscriptions on the lid document the number of times his mummy was restored and moved from its original resting place, KV7. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. (Images courtesy of Petra Lether)

Conundrum of Ramesses’ Coffin

Based on docketed evidence we know that Ramesses II first found refuge in the burial place of Seti I, and eighty-six years later was transported to the tomb of queen Ahmose Inhapy (Eighteenth Dynasty). After the passage of another thirty years he made his last journey and was deposited in the family-crypt of the priest king Pinudjem II at Deir el-Bahari (DB320); and lay concealed there for almost two thousand years until Émile Brugsch officially discovered the cache in 1881. These details of the king’s post-mortem travels are inscribed in Hieratic on the lid of his coffin.

- Archaeologists unearth tomb of Queen at the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses II

- The Secrets and Treasures of KV5, the Largest Tomb Ever Found in Egypt

![Based on his superlative research skills, Dr Nicholas Reeves eliminates proposed candidates for the original ownership of the coffin in which Ramesses II was interred. Beginning with Akhenaten’s co-regent Neferneferuaten Nefertiti who later ruled as sole Pharaoh Ankhkheperure [no epithet] Smenkhkare-Djeserkheperu, (CC BY-SA 2.0), Tutankhaten/amun (CC BY-SA 4.0),(Hossam Abbas) Aye, Horemheb (CC BY-SA 3.0) and finally, Ramesses I (Paramessu) (CC BY-SA 2.5) – Reeves offers strong arguments that rely on artistic and inscriptional evidence for striking out all names except Horemheb. (Photos clockwise: Dmitry Denisenkov, A. Parrot, Hossam Abbas, Captmondo and Keith Schengili-Roberts.)](https://www.ancient-origins.net/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/Based-on-his-superlative-research-skills.jpg?itok=JhiHa9hi)

Based on his superlative research skills, Dr Nicholas Reeves eliminates proposed candidates for the original ownership of the coffin in which Ramesses II was interred. Beginning with Akhenaten’s co-regent Neferneferuaten Nefertiti who later ruled as sole Pharaoh Ankhkheperure [no epithet] Smenkhkare-Djeserkheperu, (CC BY-SA 2.0), Tutankhaten/amun (CC BY-SA 4.0),(Hossam Abbas) Aye, Horemheb (CC BY-SA 3.0) and finally, Ramesses I (Paramessu) (CC BY-SA 2.5) – Reeves offers strong arguments that rely on artistic and inscriptional evidence for striking out all names except Horemheb. (Photos clockwise: Dmitry Denisenkov, A. Parrot, Hossam Abbas, Captmondo and Keith Schengili-Roberts.)

But Egyptologists continue to be confounded by the cedar wood mummy case (Inv. Cairo CG 61020) that the sovereign was finally laid to rest in. In 1909, French Egyptologist, Georges Daressy, was the first person to note that the style of the coffin predated the identity of its final occupant, but he restrained himself from speculating as to who precisely that first owner might have been. “This coffin is one of the more intriguing, in that, it may be dated on grounds of style to the immediate post-Amarna period, having been appropriated from its original owner... for reassignment at the end of the New Kingdom,” observes Reeves, and adds, “Concerning the identity of this first occupant, although several candidates have over the years been proposed no consensus has yet been reached.”

One King Too Many

Observing that the well-preserved, if unadorned, coffin of Ramesses II made experts wonder if it was ever used earlier, the Amarna expert states, “By its perfection of finish, the face of Inv. Cairo CG 61020 speaks to having at one stage been fitted with an easily detached sheet-metal mask similar to that of the KV 55 coffin. The resultant surface was excellent – so wonderfully fresh in appearance, in fact, that it is easy to see how Egyptologists today might be misled into regarding the coffin as unfinished and never actually employed by its intended occupant.”

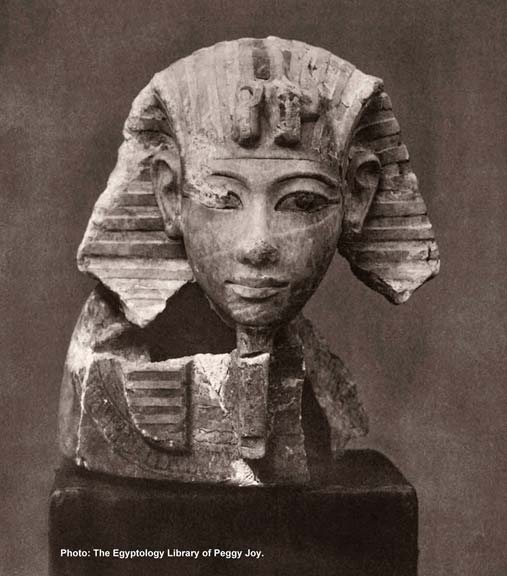

Detail of a portrait-head canopic jar lid from the tomb of Horemheb (KV57). Dr Nicholas Reeves provides convincing evidence to prove that the mummy of Ramesses II was buried in the coffin that had originally held the mortal remains of Horemheb, the last ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. (Image courtesy of The Egyptology Library of Peggy Joy).

Following a comprehensive study of the physiognomy and stylistic representations of a series of late Eighteenth and early Twentieth Dynasty kings — Neferneferuaten/Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun, Aye, Horemheb, and Ramesses I (Paramessu) — Reeves proposes Horemheb as the most likely donor. “… (based on) facial features alone, clearly the strongest contender for the initial ownership of coffin Inv. Cairo CG 61020 is Horemheb,” he opines. This theory relies, among other aspects, on the striking similarities in the facial features of a lid of a canopic jar discovered in his tomb (KV 57). “Both stylistic and inscriptional evidence point directly to the original owner of Inv. Cairo CG 61020 having been Horemheb, from whose mummy the coffin had been separated, probably at Medinet Habu, in Year 6 of wehem mesut,” the renowned Egyptologist avers. The mummy of Horemheb, though, has never been found; it probably awaits discovery in a third cache of missing royals.

Independent researcher and playwright Anand Balaji is an Ancient Origins guest writer and author of Sands of Amarna: End of Akhenaten.

The author expresses his gratitude to Dr Nicholas Reeves for allowing the use of select extracts from ‘ The Coffin of Ramesses II (2017)’, a revised version of the paper he delivered at the First Vatican Coffin Conference under the present title.

Free PDF download available here: http://www.academia.edu/7415022/The_Coffin_of_Ramesses_II_2017_

Also, watch Dr Reeves present a lecture for the Metropolitan Museum of Art – ‘ A Symposium on Haremhab: General and King of Egypt’:

Special thanks to The Egyptology Library of Peggy Joy for providing the vintage image of Horemheb’s canopic jar lid.

[The author thanks Howard Middleton-Jones, Hossam Abbas, Margaret Patterson, and Petra Lether for granting permission to use their photographs.]

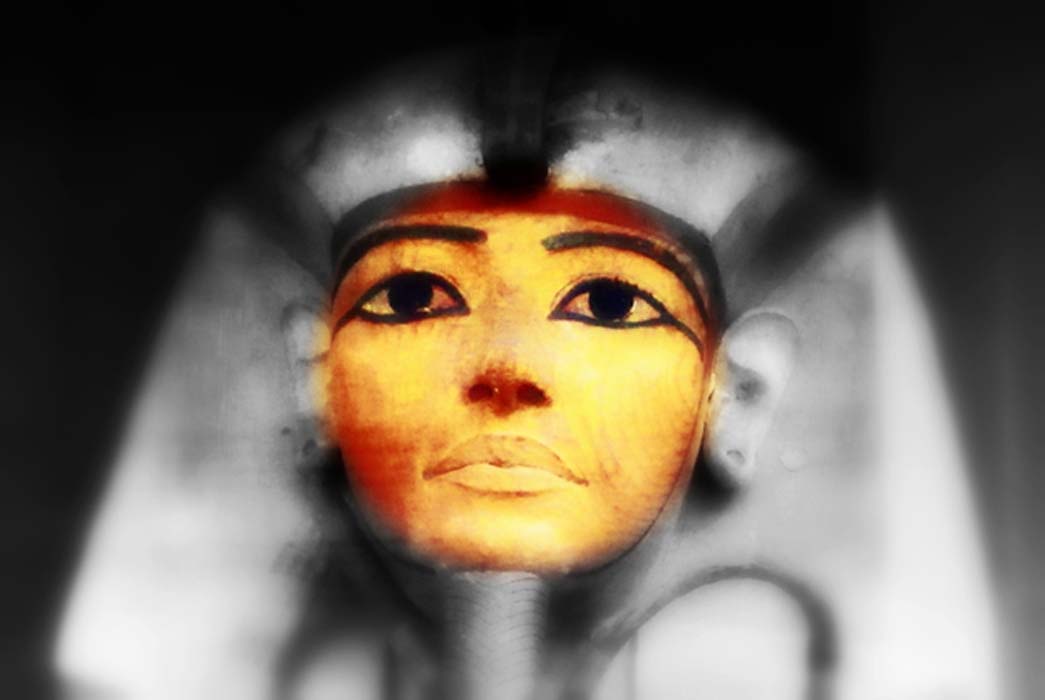

Top image: Face of the coffin in which the mummy of Ramesses II was found. (Credit: Petra Lether, designed by Anand Balaji)

By Anand Balaji

References

Nicholas Reeves, The Coffin of Ramesses II, 2017

Kent R. Weeks, The Lost Tomb, 1998

Nicholas Reeves and Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, 2008

Toby Wilkinson, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, 2010

Theodore M. Davis, The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatankhamanou, 1912

KV 5 (Sons of Rameses II) - Theban Mapping Project - http://www.thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_tomb_819.html

Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton., The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, 2004

George Wood, Finding Butehamun: Scribe of Deir el-Medina, 2016

Christopher Hugh Naunton, Regime Change and The Administration of Thebes During The Twenty-fifth Dynasty, 2011

Comments

It really doesn’t matter who, some important historical figure or not, was found in these wooden sarcophagi (meaning flesh-eating, in ancient Greek). The theories on this are probably wrong, and a diversion. The questions should focus on the ancient methodology of wrapping a dead body and seemingly preparing it for the farewell ceremony.

The first thing to note is that these are wooden coffins, not stone, which would be more intended for public display for the ages, and probably not for the purpose of continually holding a dead body. The wooden type should be seen more as a consumable implement, to hold the body during the farewell ceremony and finalize the process. Also note the shape of the base of these coffins, where the feet lay, suggest that they were intended to be STOOD UPRIGHT, not laid flat. The ‘flesh-eating’ implement contained a body wrapped in bandages and possibly soaked with an oil or some fluid, and also some packing or other objects to fill out the box. Why did they call it ‘flesh-eating’? Was the method designed to quickly consume the flesh in some process? Or was there a epidemic disease of those times and places (gamma radiation/nuclear fallout?) that attacked one’s flesh and slowly killed them? That might explain the facilities holding a lot of bodies at one time (before the whole society collapsed).

But on the methodology, which would customary for the times, my guess would be that the dead were wrapped in oil-soaked linen, and placed in the wooden box, packed with wood shavings or something combustible, and delivered to the funeral (Latin root word is torch) site, to be burned (in a pyre) as was customary IF going by the ancient texts. Finding these coffins in a state somewhere in the middle of this process suggests a total collapse of the civilization, after some great calamity of mass death.

Nobody gets paid to tell the truth.