An Empire in Death: The Extensive Remains of Persepolis

Once the stunning capital of the Persian Empire (also known as the Achaemenid Empire), Persepolis was lost to the world for almost nineteen hundred years, buried in the dirt of southwestern Iran until the 17th century. Founded in 518 BC by Darius I of the Persian Empire, Persepolis (called Parsa by the native Persians) lasted only a mere two hundred years despite the grandeur Darius and his followers abundantly heaped on its construction. Notwithstanding Persepolis’ tragic end, what remains of the Persian citadel is astounding.

The ruins of Persepolis. (F. Couin/CC BY SA 4.0)

An Elaborate Palace Equals More Power?

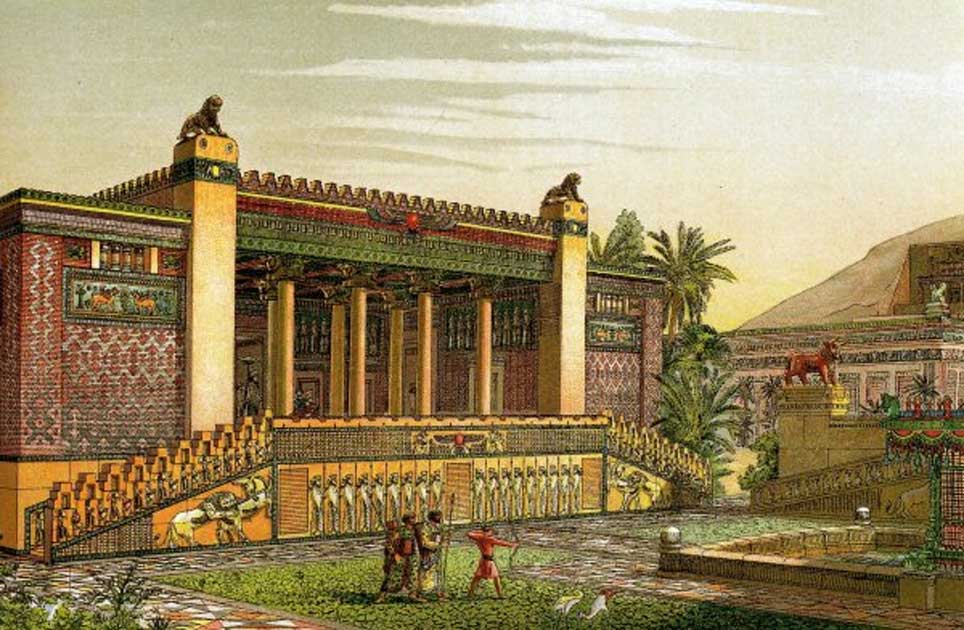

First, what is Persepolis? Besides the former leading city of one of the greatest pre-Roman empires in history, Persepolis was built at the foot of the “Mountain of Mercy” in modern day Iran. The city itself was modeled off of previous Mesopotamian complexes, the power and strength of the former Babylonian, Akkadian, and Assyrian empires resonating to the leaders of Persia in 6th century BC. Yet while Persepolis served the function of capital city, scholars believe it was used just as much to visually impress as it was to deal with court and military matters. After all, the more elaborate the palace the more power the empire must have… At least, to the minds of the ancients. Thus, the extensive terrace of Persepolis' audience hall was intentionally decorated to express the epitome of Persian leadership.

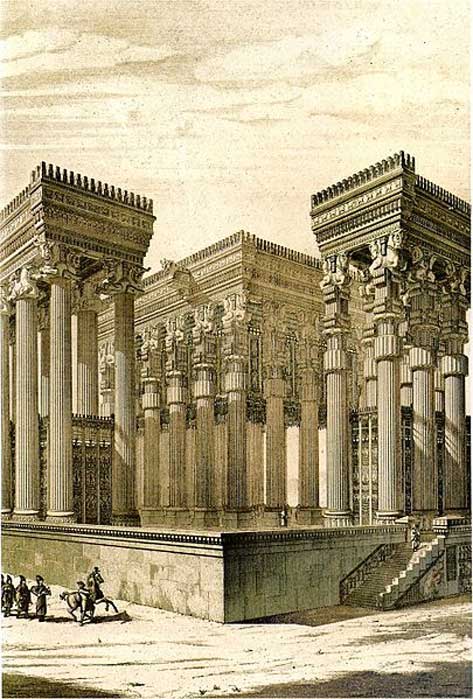

Persepolis, reconstruction of the Apadana by Chipiez. (Public Domain)

Today, the terrace and the bones of the audience hall (the Apadana) remain. The steps leading up to the Apadana (begun under Darius I in the 6th-5th centuries and finished under Xerxes I in the 5th century BC) was once made up of “grandiose architectural creation, with its double flight of access stairs, walls covered by sculpture friezes…gigantic sculpted winged bulls…” The focus of these friezes is the depiction of various members of the Achaemenid monarchy, processing along toward the entryway of the complex. Fascinatingly, many of these features still remain in varying degrees of survival. The shallowly carved friezes have withstood time, nature, and warfare, making their continuance even more intriguing.

- Deciphering Cuneiform: Helping Scholars to Get a Handle on Life in Ancient Mesopotamia

- Alexander the Great Destroyer? The Sacking of Persepolis and The Business of War – Part I

- Naqsh-e Rustam: Ancient Tombs of Powerful Persian Kings

Artwork on the eastern stairway of the Apadana. (Public Domain)

The most prominent reliefs that have survived the centuries are those located on the east, north and central stairs of the Apadana. The eastern section alone is home to a variety of depictions. The first is thought to depict the Persian king receiving gifts or tributes from his subjects. Whether this depicts an actual event, or an imagined visualization of Persian power, is debated. On the northern side is the aforementioned representation of the Persian monarchy—though, to be more specific, this image depicts the elite members of Persian culture processing with the king, likely arranged by importance.

The central images of the eastern stairs are believed to be depictions of eight Persian warriors. Keeping with the iconography of the Persian capital, these soldiers stand under a winged sun with a sphinx (a mythological creature with the body of a lion and a head of a man) on either side of the group. Art historians believe this carving depicts the Persian Immortals, an elite class of warriors constantly prepared for battle.

Modern reenactors of the Immortals in their ceremonial dress at the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire. ( Public Domain )

The northern stairs of the Apadana (as well as the southern) house similar regal images. There is an idealized depiction of an enthroned Persian king—likely Darius I—receiving more tribute bearers is most prominently displayed. Numerous Persians have been identified by name here as well—such as Pharnaces and Akinakes—which allow researchers to theorize the particular value of those permanently carved in the great audience hall.

Aside from the survival of the extensively carved relief sculptures, the bones of other formerly exceptional structures prominently remain as well. Pillars of the dark-grey marble that once belonged to King Darius' palace (called the Tachara) are still standing, some have even been re-erected in conservation efforts. Further, there are also numerous freestanding columns topped with griffins, winged bulls, or lions scattered around the area that was once a kingdom. These pillars stood as markers of the powerful empire, the lions and bulls glaring down at both citizens and foreigners alike. What makes their survival intriguing is that many remain upright despite standing completely alone. In a way, they are the epitome of the shadow cast by the capital's power, despite the site's short existence.

Zoomorphic griffin capital at Persepolis. (A. Davey/CC BY 2.0)

The Gate of All Nations

Another area of the ancient stronghold that still exists is the Gate of All Nations. The entrance-hall of the great city, the gate has since lost its roof, but it retains its monumental columns and colossal Assyrian statutes of winged bulls with human heads, called Lamassu. Two of these statues stand at the eastern threshold, while the two on the west do not have wings. These creatures were intended as semi-divine protectors of the Persian capital; they did their job rather well - until the notorious warrior Alexander the Great came barreling in.

Gate of All Nations, Persepolis, Iran. (Alborzagros/CC BY SA 3.0)

Undisturbed Tombs

Tombs of various leaders also remain undisturbed, even by Alexander the Great. Near Persepolis, the ancient necropolis (aka: city of the dead) Naqsh-e Rustam continues to house various Persian leaders who have long since passed into the afterlife.

Scholars have discovered four large tombs at this site, and have postulated that the kings within are Darius I, Darius II, Xerxes I, and Artaxerxes I, the primary leaders of the height of the Persian Empire. Regardless of the inhabitants, however, the influence of the capital is evident in the construction of the tombs, indicating that—although outside the city—the necropolis was part of Persepolis’ culture. (It should be noted that the dead were rarely kept in the primary cities; thus, the necropolis as an extension of Persepolis is an acceptable assumption.)

- Alexander the Great’s Capital Punishment? The Building of Persepolis and its Flaming Demise

- Excavations uncover large ancient gate in 2,500-year-old city of Persepolis in Iran

- The Spectacular Monumental Architecture of the Achaemenid Empire

Alexander the Great ordering Persepolis to be set on fire, Italian plate, 1534 (it may be a depiction of the burning of Rome witnessed by Nero). (Public Domain)

Though many tombs are believed to have been looted during the fall of Persepolis, the tombs themselves, the battle reliefs of subsequent monarchs, and the tomb's inhabitants remain in stunning condition.

There are two tombs directly behind the palatial complexes of Persepolis; these are thought to have belonged to Artaxerxes II and III. That they were constructed in Persepolis proper—within the city's boundaries—is an unusual concept. Following the same pattern as the necropolis tombs, their survival, in spite of Alexander the Great's flaming destruction of the city, could perhaps be viewed as the will of the gods: Persepolis was left in ruins, but two of its most important leaders withstood the flames.

Artaxerses III tomb in Persepolis. (Public Domain)

It is quite an extraordinary feat that so much of the infamous Achaemenid capital remains. Though this empire only lasted a couple centuries, its fleshy skeleton survived the fall to Macedonia in 330 BC, Seleucid rule following Alexander the Great's death in 323 BC, and the Parthian empire that lasted from the second century BC to the third century AD. In 500 years, the region saw three vastly different reigns, and Persia continued to stand tall. It's continuation in the more recent state of affairs in modern day Iran makes the survival of so much Achaemenid culture all the more astonishing. Persepolis’ survival might very well be a testament not only to its ancient value, but to its continued value as a site that once demanded respect and power.

Ruins of the Palace of Artaxerxes I, Persepolis. (Masoudkhalife/CC BY SA 4.0)

Top Image: Virtual recreation by Charles Chipiez. A panoramic view of the gardens and outside of the Palace of Darius I of Persia in Persepolis. Source: Public Domain

Bibliography

Oi-Chicago. 2007. “Persepolis and Ancient Iran: the Gate of Xerxes.” The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Accessed November 9, 2017. https://oi.uchicago.edu/collections/photographic-archives/persepolis/gate-xerxes#

Oi-Chicago. 2007. “Persepolis and Ancient Iran: the Apadana.” The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Accessed November 9, 2017. http://oi-archive.uchicago.edu/museum/collections/pa/persepolis/apadana.html

Perrot, Jean. 2013. The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. I.B.Tauris.

"Persepolis, Apadana, East Stairs." 2004. Livius.org. Accessed November 17, 2017. http://www.livius.org/articles/place/persepolis/persepolis-photos/persepolis-apadana-east-stairs/

"Persepolis, Apadana, North Stairs, Central Relief." 2004. Livius.org. Accessed November 17, 2017. http://www.livius.org/articles/place/persepolis/persepolis-photos/persepolis-apadana-north-stairs-central-relief/

UNESCO. “Persepolis.” UNESCO World Heritage Center. Accessed November 7, 2017. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/114/

“The World Heritage of Persepolis.” Parse-Pasargda. Accessed November 8, 2017. http://www.parse-pasargad.ir/en/sites/persepolis

Yarshater, Ehsan. (ed.), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.